© -Steven

Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“In terms of style, what musical influences are you aware of? The

role of bebop in your melodic lines is evident, but there's a lot more. Where

does it come from?”

“It's more a personality characteristic of

putting things together in my own way, which is analytic. Rather than just

accept the nuances or syntax of a style completely, I'll abstract principles

from it and then put it together myself. It may come out resembling the

[original] style, but it will be structured differently, and that may be what

gives it its identity. I've often thought that one reason I developed an

identity, which I wasn't aware of until recently - people were telling me I had

an identity, but I wasn't aware of one! I was just trying to play - is that I

didn't have the kind of facile talent that a lot of people have, the ability

just to listen and transfer something to my instrument. I had to go through a

terribly hard analytical and building process. In the end I came out ahead in a

sense because I knew what I was doing in a more thorough way.”

“Do you mean because of analyzing the elements in your own music?”

“In other people's music, too. If I liked

something and wanted to be influenced by it, I couldn't just take it whole hog

like some people can, like getting it more or less by osmosis. I had to

consciously abstract principles and put them into my own structure.”

- Len Lyons, The Great Jazz Pianists [p.

221]

In some form or

fashion, I think I’ve read this answer/explanation in just about every “How did

it all begin?” interview that Bill Evans ever gave and, given his immense

popularity, especially during the last decade of his life [he died in 1980], he

gave a lot of interviews.

He would sometimes

add as a corollary, that musicians who developed early due to some simplistic,

innate ability to play Jazz, usually burned out early too because they lacked a

depth of awareness about what they were doing.

Bill has also made

the statement that his stature as a Jazz pianist was due to “2% talent and 98%

hard work.”

Both his “… putting

things together in my own way…” and “…98% hard work” references were always

heartening and encouraging to me because things didn’t come easy for me in the music.

I also had to

break things down and reconstruct them step-by-step in order to find my way

through, although, in my case, the results weren’t nearly as effective as

Bill’s.

Bill’s music

touched so many Jazz musicians, whatever the instrument. Larry Bunker, gave up

a lucrative studio career for about one year to go on the road as Bill's drummer.

When I once asked

him why he took on this opportunity at such financial sacrifice, he laughed and

asked me: “Wouldn’t you have?”

Because piano and

guitar parallel each other in so many ways [each is a chording instrument], I

always thought that the lyrical nature of Bill’s approach to music would be a

natural for the guitar.

But because of his

prior musical preferences – mostly to do with Jazz-Rock Fusion and therefore

little to do with lyrical – I never expected that the guitarist that would come

forth with a treatment of Bill’s music would be John McLaughlin.

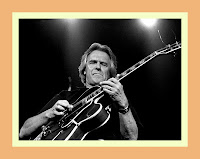

Not only did John

step-up with a superb compilation of tunes associated with Bill, he did so by

putting them into the context of a acoustic guitar quartet and added an

acoustic bass guitar!

John explains how

it all came about in the following insert notes to Time Remembered: John McLaughlin

Plays Bill Evans [Verve 314

519 861-2; paragraphing modified].

© -John McLaughlin/Verve Records, copyright

protected; all rights reserved.

“I can recall

quite vividly the very first time I heard Bill Evans play. I was about

seventeen years old and had already been subjugated by Miles Davis with his

record "Milestones." His following record was the now

"classic" record, "Kind of Blue."

Naturally I bought

this record for Miles, but, was astonished to hear the pianist Bill Evans, who

seemed to me to have a kind of empathic communication with Miles and his way of

playing.

Among the many

qualities Miles had, poignancy was one of his most eloquent; Bill understood

this exceptionally well, and had the capability of encouraging this while

accompanying Miles. Bill played many different kinds of harmonies that, though

I couldn't understand them at all, were so "right." I spent many

hours listening to that recording and, I can add, listen regularly to now.

A couple of years

later I heard his first trio record with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian. This was

a turning point in my life. The next six months were spent listening almost

exclusively to this record, and trying to analyze it while marveling at the

interaction between the three players. It was on this record that I heard

Bill's compositions for the first time and, although incapable of playing them,

did my best to try to understand his harmonic and rhythmic conceptions which

were so new to me. It was only much later, on having discovered the music of

Ravel, Debussy, and Satie, that I began to understand the origins of Bill's

harmonic viewpoint.

Time passed and I

remained as I remain to this day one of his most ardent fans. By the time I

took up residence in the USA London

In the USA Greenwich

Village that has

hosted the greatest jazz musicians of our epoch. I would go regularly to see

Bill play there and I recall one particular night when Bill's trio came on

stage to play the second set, Bill began an introduction to Nardis and he went

into what I can only call a state of grace. He played some of the most beautiful

music I have ever had the privilege to witness. I was there with saxophonist Dave Liebman, and we were both in a state of

total astonishment.

The idea of

recording Bill's music exclusively with guitars dates back at least eleven or

twelve years. The reason behind the exclusivity of guitars is probably due to

the fact that to me, Bill was a thorough romantic. The acoustic guitar is,

without doubt, one of the most romantic instruments, and I felt that I could do

justice to his music in this way.

At the beginning

of 1992, I decided that the time had come and began work on the selection of

Bill's compositions and the conception of how to realize this already long

dream of recording his music in this way. I decided to employ six guitars, five

acoustic and one acoustic bass guitar. This proved to be an arduous task of

even greater proportions that I had imagined.

To help me in this

work I asked for the help of my own student, Yan Maresz, himself a composition

graduate of the Julliard school in New York

In a sense this

work was almost "classical," and to solve this problem, I had the

good fortune to meet a classical guitar quartet - The Aighetta Quartet - in my

part of the world. Prior to my meeting them, they were not familiar with Bill's

music, but subsequently became enamored with the compositions and devoted

hundreds of hours to mastering the parts and particularly the task o/ adapting

their style o/ music.

There remained,

however, the thorny problem of improvisation. For all his classical training,

Bill was a jazz musician and a supreme improviser, and in the majority of his

recorded works, improvisation has equal importance with his compositions.

Naturally I needed

to include this element in my work and whereas in a normal jazz situation, the

group plays the head and then improvise around the changes, this could not

apply to this project.

To solve this

problem, I took the artistic liberty of writing new music for the five other

musicians upon which I would improvise. This also proved to be quite demanding.

If you listen carefully to Bill's records, after the composition and the

improvisation begins, there is always a forward movement, a kind of further

development in the piece.

This is what I

have done in this recording. What was quite tricky was to have Bill's music lead

into mine in the most natural way possible while at the same time giving this

forward movement and allowing me to improvise, while keeping the essential

characteristics of his piece. And of

course, the reverse was necessary, to leave my music and improvisation and flow

naturally back into Bill's tune for the ending.

Altogether this

record was a real labor of love and one that I am very happy to have made.

Firstly for Bill and his music which has enriched my life, secondly for the

guitar, and the combination of these two elements.

I give my heartfelt

thanks to Frangois Szonyi, Pascal Rabatti, Alexandre Del Fa and Philippe Loli

of the Aighetta Quartet, to Yan Maresz for his great work in the preparation of

the scores, to Abraham Wechter for my wonderful instrument, Jim D'Addario for

his strings, and most profoundly of all, to Bill Evans.

John Mclaughlin June

10, 1993 ”

The following

video montage features John, Yan and The Aighetta Quartet on their version of

Bill’s We Will Meet Again.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments here. Thank you.