© -Steven Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“I loved and respected Louis Armstrong. He was born poor, died rich and never hurt anyone along the way.”

- Duke Ellington

When the world was young and college students read books, one of my professors assigned our class a series of period novels.

“How can you understand what the world was like then if you read about it in books written now?”

“Context is everything.”

“These novels will give you the ‘flavor of the times.’”

In addition to offering a detailed view of the stateside and overseas musical journeys of the last two decades of Louis Armstrong life, this is exactly what Ricky Riccardi succeeds in doing in his book - What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years.

He puts Louis’ life in the context in which he lived it: the US

What emerges as a result is a fitting tribute to a man, who by any standard of judgment, was a creative genius and not the Jazz equivalent of Pagliacci, the [operatic] clown, an epithet hung on Pops during his later years by those who never fully understood him or appreciated him.

The magnitude of Louis Armstrong’s achievements during the last 20 years or so of his life and author Ricky Riccardi’s work in documenting them is underscored in the following quotation from Dan Morgenstern , Director of The Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University:

“This is not only a tale of interest to Jazz fans or academics but the climatic portion of the inspiring life story of a man who, against all odds, rose from extreme poverty and discrimination to become, indisputably, one of the stellar figures of the twentieth century…. We need this book.”

Or as, Terry Teachout, the esteemed writer about Jazz and American culture, states:

“The story of Louis Armstrong’s later years is the great untold tale of postwar Jazz. Now Ricky Riccardi has told it to perfection. What a Wonderful World is a unique and indispensable landmark in American scholarship, a weathervane that will point the way to all future writings on his life and work.”

The editorial staff at JazzProfiles is honored that Ricky Riccardi consented to the following interview. You can find out more about Ricky and his continuing activities on behalf of Pops and the Louis Armstrong House by visiting his website.

I would also like to thank Josefine Kals, Publicist at Pantheon and Shocken Books, for her consideration and for arranging the interview with Ricky.

01. Many Jazz fans view Pops’ early career as separate and distinct from the popular figure he became in his later years. What gave you the idea to see the continuity between these two periods?

It was just from doing the listening. Anyone can go out and get a “Best of the Hot Fives” disc, listen to only “West End Blues,” “Potato Head Blues” and “Cornet Chop Suey” and come away with the impression that Louis was a pioneering jazz trumpet player of the 1920s…and that’s about it. Though they did not change the course of jazz, I think it’s important to listen to and appreciate “Sunset Café Stomp,” “Irish Black Bottom,” “That’s When I’ll Come Back to You” and the other more humorous Hot Fives and Hot Sevens.

Second, I did a lot of work with Louis’s scrapbooks and reading about his day-to-day activities. The Hot Fives and Sevens were blips on his radar; he didn’t think he was changing jazz history, he just wanted some quick money! But when you read about him playing pop tunes nightly, singing, getting laughs, doing comedy routines, dancing, you realize that the trailblazing trumpet playing was only one aspect of a man who was a genius all the way around. So, as I ask in the book, why not take all of him?

02. How did you - someone born about a decade after Pops died - ever become interested in Pops’ music to the extent that you have?

I was born in 1980 and have enjoyed very little popular music created after 1980. In elementary school, I was listening to Motown and 1950s rock and roll. In middle school, I went backwards to Al Jolson and ragtime. Thus, I’ve always enjoyed old sounds and especially old movies. When I was 15, I rented “The Glenn Miller Story” with Jimmy Stewart. I knew nothing about Louis, but when he came on and did “Basin Street Blues,” it knocked me out. I immediately asked my mother to take me to our local library and I checked out a cassette, “16 Most Requested Songs,” a compilation of Louis’s 1950s Columbia

03. What is your background in music?

I’ll be 31 in September and I’ve been playing the piano since I was 7 or 8. Just basic lessons and then I taught myself jazz and how to improvise when I was in high school. I formed a trio in my senior year and though the personnel has changed, I’m still leading it out of Toms River, NJ. I love playing but I’ve never taken it too seriously. I’m not an innovator by any means; I just like playing songs I like and bringing the sounds of jazz to an area that really doesn’t know what it is (I once jokingly billed myself as “The Jazz King of Toms River” because I’m the entire Toms River jazz scene!).

04. What was your purpose in writing this book?

I just wanted more people to respect the entirety of Louis Armstrong’s life and career. This is one of our great geniuses; hundreds of years from now, he will be discussed like we talk about Bach and Beethoven. Since he’s died, it’s become okay again to admire the Hot Fives and Sevens, but no one really feels the need to go any further. Online jazz forums barely mention Louis; he might get one article a year in the major jazz magazines. I think too many people take him for granted: “Yeah, he was incredibly important in the 1920s but then he went all showbiz and I never bothered checking anything else out.” Those people are missing out.

And then there’s the people who have problem’s with Louis’s persona and still think he was soft on racism. By using so many of Louis’s private tapes, I’ve tried painting a full portrait of the man, someone who had very complex feelings about racism and a man who was a real Civil Rights pioneer. It’s time he gets respected for that, too.

05. If the reader had to take away three main points about Pops after reading your book, what would these be?

1) Louis Armstrong was nobody’s Uncle Tom and took heroic stands for his race in the 1950s and 1960s. 2) There’s no such thing as the two Armstrong’s: the young genius and the old clown; it’s one man. 3) Louis Armstrong made some of his greatest and most challenging works in those last 24 years of his life….get out and listen to them!

06. Joe Glaser, the impresario, was a key figure throughout Pops’ career. How would you describe the relationship between he and Pops?

Complex. Many people have painted Glaser as nothing but a slave driver, working Louis too hard and getting rich from it. And yes, there’s an element of that. But people don’t realize that Louis had a lot of control; he WANTED to work that hard and would get upset if Glaser gave him too many days off. And Louis was not afraid to stand up for himself, threatening to retire if Glaser couldn’t make things happen for him.

So for all of Glaser’s faults, he gave Louis a stress-free life for the last 36 years of Louis’s life: he never had to worry about money, about taxes, about hiring and firing musicians, about getting gigs, nothing. All he had to do was show up and play and I think a lot of musicians would have killed for a deal like that.

07. It’s not uncommon for fans of an earlier era of a musician’s career to dislike the music of these musicians as their careers progress: Miles Davis comes to mind with his transition from hard bop to fusion & rock; Stan Kenton’s playing of the music of the Beetles during his orchestra’s last decade in the 1970s; Pops’ move to popular songs such as Hello, Dolly, Mack the Knife and What a Wonderful World. Why do you think that this is so?

Ah, I think sometimes an artist is damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. If Louis went around playing in Hot Five settings from 1925 to 1971, people would have wrote him off as someone simply repeating himself and never offering anything new. Louis changed with the times but never compromised his art; he still sounded like Louis Armstrong, whether it was “A Kiss to Build a Dream On” on Decca, “Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy” on Columbia, singing the Great American Songbook on Verve or doing “Hello, Dolly.” Louis loved ALL kinds of music and always said that where he came from, a real musician was taught to play different kinds of music, not just one style.

So people and critics might grab on to one part of a musician’s career—the Hot Fives and Sevens make up about three total hours of Louis’s life in the 1920s—and bemoan everything else as this great change, but they don’t realize that artists change themselves. Lester Young got it in the 1940s and 1950s because he wasn’t the swashbuckling playing of “Shoe Shine Boy.” So what? He was Lester Young and he had a story to tell and you should listen to it. Same with Louis; he matured over the years and learned how to say more with less. In 1956, he was claiming he was playing better trumpet than ever before in his life, but it’s like people expected him to say, “Boy, I’m not playing like I used to in the 1920s, I might as well keep making commercial songs.” No, Louis was still doing great things and he knew it. I quote a lengthy conversation Louis had with a disc jockey who described one of Louis’s Decca pop records, “I Laughed at Love,” as a “commercial” number. Louis scolded the D.J. and said there was “nothing that can outswing it.” There’s this thing where people feel, “Well, I don’t like it so the artist must not have liked it either.” Not true. So you have to stop listening with preconceived notions and appreciate who the artist was in those moments, not who he or she wasn’t.

08. Over the years, Pops played with many musicians. Who among them were his favorites and why?

He seemed to have a thing for trombonists: he absolutely adored Trummy Young, Jack Teagarden and Tyree Glenn and they all became his closest friends when each was an All Star. He was often hard on his drummers, though, and really did not get along with Earl Hines during his tenure with the All Stars. But those trombonists, they were super close with Louis.

09. In coming to know Pops as you have through your research, what were you say were some of his strong points both as a person and as a musician; what were his weak points?

Got time for another book? There’s too many strong points to list but I’ll make a go of it. As a person, he was just an incredible human being. He treated fans like he had known them for years. He was incredibly generous. He demanded respect—and if you didn’t give it to him, watch out for his temper!. He decried social injustice and had no tolerance for violence of any kind. He put his audiences first and lived to make them happy. He was a complete professional who worked strenuously to make sure his live performances were top notch, giving 110% even if there were a handful of people in the room. And as a musician, I don’t think there’ll ever be another who had such an impact as a trumpeter AND as a singer.

But of course, he was no saint. He smoked marijuana religiously, he cheated on his wives at pretty much every chance he got. He could be stubborn. And perhaps he didn’t speak up enough for certain things he believed in, such as some ideas that George Avakian had for Louis to record at Columbia, but Joe Glaser killed them without a fight for Louis. I write about Louis singing the word “darkies” as late as 1951 and that’s nothing to be proud of. So the man did have his faults and I’m not afraid to call out a recording that I find so-so. But the good far outweighs the bad.

10. In your book, you identify Pops’ May 17, 1947 concert at Town Hall in NYC as a sort of a turning point in terms of what was to follow later in his career. Why this performance and not a different one?

Town Hall is where the writing on the wall really became apparent. Louis had success with Edmond Hall’s sextet at Carnegie Hall in February, but his big band shared the bill on that one. And he played with small groups on a “This is Jazz” radio broadcast, and another broadcast with Jack Teagarden, on the same day in April 1947. But Town Hall was an entire evening devoted to small group performances. It surrounded Louis with some of the finest musicians then on the scene. The concert sold out immediately and was a hit with critics. The big band era was dying out and that one evening at Town Hall made it abundantly clear that this was the way to go.

11. Although Jazz critics viewed them as “commercial,” why was Pops’ so comfortable with A Kiss to Build A Dream On, Lucky Old Sun, Blueberry Hill, Mack the Knife, Hello, Dolly, and, What a Wonderful World.

Because these were songs where he could “see the life of them,” as he put it. Louis, as I mentioned, believed in playing all kinds of music. He didn’t think he just had to play straight jazz or standards. He loved sentimental songs and novelties. So he never prejudged a tune. When he was handed “Blueberry Hill,” he thought about “some chick” he once knew. When he was handed “Mack the Knife,” he thought of some characters out of New Orleans Corona Queens . So he never complained, “Oh no, what is this, I should be recording nothing but instrumental hot jazz!” He found something to relate to in every song he performed, which is why when you listen to Louis in such settings, he always sounds completely connected to the tune and never like he’s just slumming.

12. When they were appearing together in the 1953 movie, The Glenn Miller Story, the legendary actor, Jimmy Stewart, said of Pops: “That man really is Jazz personified.” What did Jimmy Stewart mean by that remark?

To probably the great majority of inhabitants of the planet earth in 1953, that if you heard the word jazz, you thought of Louis Armstrong. And it’s true. Think of that whole package, the trumpet playing, the high notes, the solos, the improvisations, the compositions, the singing, the scatting, the repertoire, the man WAS jazz. And obviously, I still feel that way though I think that to the majority of people who hear the word “jazz” today, they’ll think of Miles or Monk or Coltrane. Louis has kind of been put on the back burner a little bit and that shouldn’t be. Why? Because he was funny and recorded pop songs? He was just as serious about his music as the rest of them.

13. What brought about Pops’ 1954-55 “Columbia

It’s more of a “who” brought them about: it was the legendary producer George Avakian, still going strong at 92. George had ideas to have Louis and his working group, the All Stars record material by great composers such as W. C. Handy and Fats Waller, stuff that wasn’t in Decca’s plans for Louis. After some wrangling with Joe Glaser, Avakian was allowed to make two albums, “Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy” and “Satch Plays Fats,” two of the greatest albums Louis ever made and really, two albums that belong in the pantheon of great jazz works created in the 50s. Both albums were critically lauded and sold well so Glaser let Avakian record Louis exclusively for almost a full year, starting in September 1955. Avakian came up with a hit record when he had Louis record “Mack the Knife,” then followed it with the turbo-charged album, “Ambassador Satch,” capturing my favorite edition of the All Stars at their peak on a variety of live and studio performances. But just as Avakian was getting rolling, Louis’s popular started climbing into the stratosphere. In the book, I detail how Glaser strung Avakian along for a while but refused to sign an exclusive contract, knowing that there was more money to be made by using Louis as a free agent, available to only the highest bidders. So the Columbia

14. Besides the obvious monetary relationship, what do you think accounts for Joe Glaser’s unflagging support of Pops’ during the “[racial] showdown of 1957”?

I think Glaser truly admired Louis and you can even say he loved him. That didn’t stop him from taking advantage of him and stuff like that but I think he admired Louis’s courage in taking that stance against Eisenhower and the government. Others, such as Louis’s road manager, a cronie of Glaser’s named Pierre “Frenchy” Tallerie, tried to downplay Louis’s words to the press but Glaser never budged and was quoted in newspapers and magazines such as “Jet” saying how proud he was of Louis for saying this. I’m sure deep down, he was having a heart attack over it, but he knew he wasn’t going to change Louis’s mind so he did the next best thing and stood behind his prized client during a pretty tenuous situation.

15. “Entertaining” and “show business” were always a big part of Pops’ life. How would you describe Pops’ philosophy of entertaining and why was it so important to him?

Louis was a natural “ham actor,” as he once put it. Even in his early days, when he was supposed to be such a “serious” artist, he was known just as much for his onstage antics as he was for his trumpet playing. He was a true entertainer and saw no problem with mixing music and showmanship….especially because he took his music so seriously. As he once told an interviewer, getting applause for showmanship and jokes is nice, but it doesn’t matter if you’re not playing the notes correctly.

And remember, yes, Louis was heavily influenced by musicians like King Oliver but he also never got tired of talking about his love of vaudeville entertainers such as Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Bert Williams. Some people try making it a “minstrel” thing but Louis just loved comedians. His personal record collection was filled with albums by Redd Foxx, Moms Mabely and Pigmeat Markham. And his private tapes are filled with hours and hours of Louis and friends telling jokes offstage…always with Louis telling them the best and laughing the loudest. He even typed about his favorite jokes in a 100+ page manuscript that is absolutely fascinating (and available to researchers visiting the Louis Armstrong House Museum Queens College

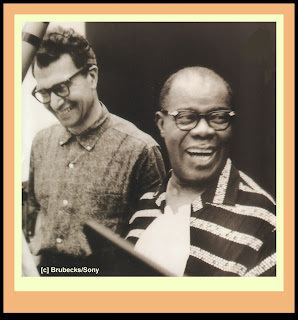

16. Why was Pops’ performance in Dave and Iola Brubeck’s The Real Ambassadors such a moving and meaningful experience for him? Does this project have a special significance in Pops’ life beyond the music itself?

I think it does. First, there was the challenge of learning an entire score of new material, something he really had never done before. Even on Verve albums with Ella such as “Porgy and Bess,” I’m sure he was at least familiar with some of those great songs. But the Brubecks wrote all these new songs with Louis in mind and Louis rose to the challenge by nailing it. Also, there was the subject matter, songs about race, politics, religious, etc. This was deep stuff and Louis responded with more seriousness and sensitivity than even Brubeck imagined bringing tears to those who heard Louis in the studio or those who witnessed the only live performance of “The Real Ambassaors” at Monterey in 1962. I really think he considered it one of the highlights of his life (he dubbed it many, many times on his private tapes, right up to the end of this life) and proudly told reporters that Brubeck had written him “an opera.”

17. To elaborate further on a portion of an earlier question, what were the factors that made Hello, Dolly such a wildly unexpectant hit for Pops?

It’s one of life’s great mysteries but the simple explanation is that it’s a fun, catchy, swinging Louis Armstrong record. No one knew the song; the play wasn’t even open when Louis recorded it. The Beatles were all over the place, not small-group Dixieland complete with banjo. And Louis hadn’t even stepped foot in a recording studio in two years so it wasn’t like his records were exactly hot commodities. But the stars really aligned for that record. Some people bought it as soon as they heard Louis’s personal touch, “This is Louis, Dolly.” Those in his band said Louis wasn’t a big fan of the song but again, he gave it his all, played some fine trumpet and when all was said and done, he had the biggest hit of his lifetime, at 63-years-old. It’s quite stunning but if you just taken it for granted, give “Hello, Dolly” a fresh listen and I guarantee you’ll find it pretty irresistible.

18. Why did Patrick Scott’s 1965 Toronto Globe Mail article and Richard Meryman’s 1966 Life Magazine profile have such a huge impact on Pops’ later life?

Those articles didn’t have as much of an impact on Louis’s later life as they reflected Louis’s mental state in what was a pretty rough time for him. He had major dental work in the spring of 1965 and when he got back to playing, things weren’t exactly the same. He still sounded great but he could no longer execute his solos and ideas 100% as he had just a few months earlier. He was in his mid-60s and tired and needed more rest. But at the same time, because of “Hello, Dolly,” he was more popular and more in demand than ever before so he kept pushing himself, even though internally, he was getting more depressed.

The Scott and Meryman articles are important because they caught Louis with his guard partially down and Louis’s depressed state comes through loud and clear. The Scott article recounted events from the summer of 1965, while the “Life” piece, though not published until April 1966, was also done around September 1965. And in both pieces, Louis wonders if he should have stayed in New Orleans

But I do think it must have gotten back to Glaser. Because in 1966, you start seeing more days off in between tours of one-nighters and in one remarkable stretch, Louis had a steady gig at Jones Beach in Long Island between June and September 1966, getting to stay at his home every night for four months. So I do think Glaser made an effort to give Louis a little more breathing room but there were still plenty of grueling tours left. Two All Stars, Billy Kyle and Buster Bailey, even died in 1966 and 1967 respectively.

The postscript to it all is Louis finally got his wish in 1968 when ill health forced him to pretty much retire for two years. He made TV appearances and the occasional record but really just lived at home, practiced a bit of trumpet and worked on his hobbies. But once doctors gave him clearance to play with his All Stars again, he came to life and even though those few engagements probably contributed to his death, he was back onstage and for all the depressing thoughts he told Scott and Meryman, he lived to be on that stage, entertaining his fans.

19. If the general public associates Pops’ with one, particular tune, it may be What a Wonderful World. How did this recording come about?

The producer Bob Thiele took credit for it. After “Dolly,” Louis began making a series of erratic recordings for Mercury and Brunswick Corona Queens and grew to love the tune. However, the president of ABC records thought it was suicide and didn’t want to release it. He eventually did but gave it zero promotion in the United States U. S.

20. On page 277 of you book you state: “Before singing What a Wonderful World on the 1970 David Frost Show, Armstrong said about the lyrics, ‘They mean so much.’ Is Pops’ comment an appropriate summation for the main theme of your work: “The Magical World of Louis Armstrong?” Put another way, did Pops’ view his life as a “magical world?”

I think he did and he didn’t. In many ways, he downplayed a lot of what he did, referring to himself as a “salary man,” living in a modest home, wanting to be treated as any ordinary working citizen. He felt he got as far as he did through hard work and by not being lazy and in that sense, he probably didn’t see any “magic” in it. But at other times, he did look at his life and express some amazement at where he came from and what he became. When asked about being called an “Ambassador of Goodwill,” he once replied, “It’s nice because, I mean, the kid has come a long way.” And he knew the effect he had on his fans around the world. It truly was magical. “A note’s a note in any language” he was fond of saying. He could go behind the Iron Curtain, where you couldn’t find a single Louis Armstrong record, and end up a hero, winning standing ovations and being mobbed for his music. He stopped a Civil War in the Congo