© -Steven

Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

As has been the

case recently with many of the earlier postings that have appeared on the blog in multiple or sequential formats,

the editorial staff at JazzProfiles has taken the

opportunity to combine these into single feature to make them more accessible

in the blog archives.

I have also

standardized the fonts and enhanced the accompanying graphics and images.

Lastly, I have

added two videos to give the reader a sampling of the actual music under

discussion.

This feature

originally posted to the blog in two parts feature on July 6,2008 and July 8,2008, respectively.

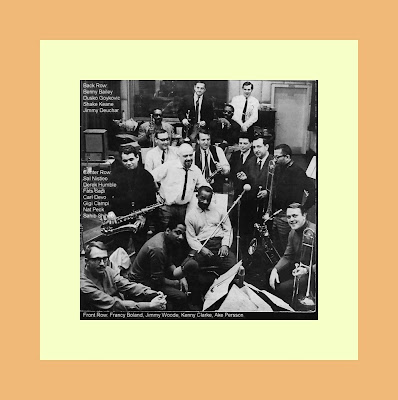

The Improbability of the Clarke Boland Big Band – Part 1

For a variety of

reasons, I missed the Clarke Boland Big Band [CBBB] during most of its

existence on the 1960s Jazz scene . Although I recall that many of my friends

raved about the band, and I remember seeing their initial Atlantic LP – Jazz

is Universal – on display in record stores, I never actually heard the

band’s music until over 20 years after it had ceased to exist in 1972.

Thanks to the

glorious era of re-issuance that followed the development of the compact disc,

I now know what all the fuss was about.

What a band! One of the all-time great bands in the history of Jazz.

Yet, judging by

the opening paragraph from the chapter on the band in Mike Hennessey’s, Klook:

The Story of Ken ny Clarke [London

And given Mr.

Hennessey’s description of how the band came together and what it took to

maintain it during the 12 or so years of existence, the fantasy world

implication of the Disney art that adorns its More Jazz Japanese

release may be more fitting than comical.

Of course, as a

former drummer, how can you not love a big band that has two? But that’s

another part of the improbable story as told by Mike Hennessey.

© - Mr. Hennessey , copyright protected; all

rights reserved.

“Almost everything about the Clarke‑Boland

Big Band was improbable. It was invented, nurtured, nourished, fussed over,

financed, promoted and absolutely adored by a German-born Italian socialist

whose qualifications for band management were that he was a trained architect

and owner of a flourishing coffee bar in Cologne United States

And Pier‑Luigi

'Gigi' Campi, the man who made it happen, is quite emphatic that the band

simply could not have existed without Ken ny Clarke. 'We needed his magic touch he

told me.”

As a teenager in

Italy

But it was

when Campi heard a Charlie Parker record in 1948 that he started to become a

real jazz devotee. In 1949 he attended an international meeting of young

socialists from all over Europe

and, as he alighted from the train in Zurich France

political

meeting that evening and attend the concert instead. Gigi recalls:

There was another group

mentioned on the poster but the names meant nothing to me. Django played the

first half and I was really excited by the music. But in the second half, this

group of black musicians played ‑ and the music sounded strange, but wonderful.

I remember coming out of that concert feeling absolutely exhilarated. I was

telling myself, 'Django was fine ‑ but those black musicians, they were really

fantastic.' Three years later, James Moody and his group were touring Germany Munich

The

drummer, of course, was Ken ny Clarke, who'd been a member of the band that

had played

the second half of the Django concert in 1949. And Gigi discovered that the men

with Ken ny at that time had been Miles Davis,

Charlie Parker, Tommy Potter and Tadd Dameron, fresh from the historic first

Jazz Festival.

‘I went backstage after the concert/ Gigi says, 'and had my first

close‑up of what you

later called "the thousand‑candle‑power-grin". Ken ny impressed me enormously, not only as a

drummer but as a person.'

The success of his coffee bar enabled Gigi Campi to indulge his

love of jazz by

organizing concert tours and producing jazz records. He set up a

tour for the Chet Baker Quartet and recorded Lars Gullin, Lee Konitz and Hans

Koller for his Mod label. His enthusiasm, however, outstripped his entrepreneurial

flair as a jazz promoter. He lost $10,000 on a 1956 Lee Konitz tour.

But I learned something from

being on the road with Lee. My friends and I were big fans of cool jazz at that

time, but Lee would always be singing Lester Young solos on the train. I think

that tuned me in again to the swing‑band era. He also said that the next time

he came on tour, I should make a point of hiring Ken ny

Clarke to play drums. But, after this tour had flopped, I decided to cut my

losses and quit the jazz business. However, I remembered Ken ny

Clarke, of course, and I resolved that if I decided to get involved with jazz

production and promotion again, the first thing I would make sure of was that I

had a good rhythm section.

At the time

that Campi was beating a retreat from jazz promotion, Francois 'Francy' Boland,

a twenty‑ six‑year‑ old pianist, composer and arranger from Namur , Belgium United States

Francy had

also written arrangements for the German orchestras of Kurt Edelhagen and

Werner Muller and it was through Edelhagen that Gigi Campi first became aware

of his arranging skills. Kurt Edelhagen was the leader of one of Germany's most

successful big jazz bands, a multi‑nation outfit which he assembled in 1957 and

which, though a touch bombastic and lacking in subtlety, was one of the most

impressive large jazz ensembles of its time in Europe and boasted some fine

soloists ‑ including, at various times, Dusk Gojkovic, Jiggs Whigham, Carl

Drevo, Peter Trunk, Jimmy Deuchar, Shake Keane, Ronnie Stephenson, Wilton

Gaynair, Ferdinand Povel, Benny Bailey, Peter Herbolzheimer, Derek Humble and Ken Wray.

Edelhagen

had a contract with the West Deutsche Rundfunk in Cologne

Said Campi,

Francy was sending all the arrangements he

was writing for Basie to Edelhagen as well, including 'Major's Groove', which

later became 'Griff's Groove', a feature for Johnny Griffin. I had met Francy

in 1955 when he was working with Chet Baker after the death of Chet's pianist,

Dick Twardzik, and I remember enjoying his piano playing. Now, having listened

to some of his arrangements, an idea was forming in my mind.

Later

Francy, who had returned from the States after some disagreement over payment

for the Basie arrangements, came to Cologne Ken ny Clarke and a group of musicians from the

Edelhagen band: Chris Kellens (trombone), Eddie Busnello (alto), Fats Sadi

(vibes) and Jean Warland (bass). Recordings by this group were later issued by

the German Electrola Company as Don Wails with Ken ny.

The first

real Clarke‑Boland recording, however, was made in Cologne Ken ny and Francy with Raymond Droz on alto

horn, Chris Kellens on baritone horn, Britain's Derek Humble on alto, Austria's

Carl Drevo on tenor and Jimmy Woode on bass. That was the firs manifestation of

what was to become the regular rhythm section of the Clarke‑Boland band. Campi

sent the tape to Alfred Lion of Blue Note who hailed it as 'fantastic' and

released it under the title The

Golden Eight.

Both the Electrola and the Blue Note albums had been recorded by a brilliant engineer,

Wolfgang Hirschmann, who was to become the engineer of the CBBB over the

next decade. Campi, Boland and Clarke all had the highest regard for

Hirschmann. Ken ny once said that the three sound engineers

he really respected were Hirschmann, Rudy van Gelder and a German technician at

the old Paris Barclay studios called Gerhard Lehner, because they all used just

one mike above the drums to capture his sound. 'Sometimes they would use extra

mikes for the hi‑hat and snare drum, but I preferred just one,' Ken ny said ‑ which is another illustration of

his belief in the efficacy of simplicity.

It was

seven months later, in December 1961,

that the Clarke‑Boland Big Band came into being in the Electrola

Studios in Cologne ‑ and its recording debut was fortuitous. The session had

originally been a date for Billie Poole, who

was playing at the Storyville Club in Cologne Riverside Ken ny and Francy, to assemble 'a little big

band' for the date. Francy wrote the arrangements and the line‑up was Benny

Bailey, Roger Guerin, Jimmy Deuchar and Ahmed Muvaffak

Falay (trumpets); Nat Peck, Ake Persson (trombones); Carl Drevo, Zoot Sims

(tenors), Derek Humble (alto), Sahib Shihab (baritone), Francy Boland (piano),

Jimmy Woode (bass) and Ken ny Clarke (drums).

All was set

for the record date, when, one week before the musicians were due to assemble

in Cologne Atlantic , and aptly titled Jazz is Universal.

Campi told

me,

The opening track on that

album, 'Box 703 ,

Washington DC

I said, 'You mean you're not

happy with the fee? You want more?

'No. I mean that I should be

paying you for the privilege of playing in a motherfucking band like this after

all these years.'

And that was the kind of

spirit that developed ‑ the music and the feeling became more important than

the money ‑ a really remarkable thing when you consider how hard musicians

sometimes have to fight to get paid, or to get paid adequately.

What was

especially important about Jazz is

Universal was that it proved beyond a doubt that jazz was no

longer the exclusive preserve of American musicians. 'The thoroughly integrated

sound that emerged from this band,' wrote 'Voice of America' producer and

presenter Willis Conover in the liner note for the album, 'is convincing

evidence that international boundaries have no meaning at all to the practicing

jazz musician.'

Seven of

the thirteen musicians in the band were European and their ability to hold

their own with their American colleagues did no damage at all to the cause of

winning a just measure of appreciation and recognition for some of the

excellent European jazz musicians who were emerging. An indication of how the band's

enthusiasm for the music was as abundant as its musicianship is the fact that

the album was recorded in just four hours!

It was

always Campi's goal, with the CBBB, to create a band which had an immediately

recognizable identity ‑ which was why he wanted Francy Boland to write all the

band's arrangements. Boland's very special concept of arranging helped to

achieve this aim, and the brilliant solo and section work of a band whose

members loved to play together and who developed such a great personal and

musical rapport, did the rest.

The key

elements, according to Campi, were first of all the rhythm section: 'I knew

when I heard Ken ny, Francy and Jimmy play together for the

first time that I simply had to build a big band around them.' A second crucial

element was the magnificent lead trumpet and solo work of Benny Bailey ‑ a

musician for whom both Dizzy Gillespie and Thad Jones expressed admiration

tinged with awe. The third was the immaculate lead alto saxophone and

brilliant, serpentine solo work of Derek Humble. And a fourth was the massive

loyalty and surging enthusiasm of the big Swede, Ake Persson, who was an

indefatigable champion of the band. Ake was also a formidable trombonist. Nat

Peck once said, 'Every time I sit down with him it's like I'm hearing him for

the first time Thrilling! I've never worked with anyone who has

stimulated me so much.'

Encouraged

by the success of the Universal album, Gigi Campi decided to assemble an

even bigger band for the next record date on 25, 26 and 27 January

1963 . Two albums

resulted from this session made with a twenty‑one‑piece orchestra ‑ six

trumpets, five trombones, five saxophones and an augmented rhythm section with

Joe Harris on percussion ‑ Now Hear

Our Meanin' released on CBS,

and Handle with Care, released on the Atlantic

label. Britain United States New York

The band

needed a bass trombonist ‑ and nobody seemed to be able to come up with a suitable

candidate. Then Ake Persson came to see Nat Peck, clutching an album. 'I've got

him,’ he said. 'Listen to this.' And he played a track from the Gil Evans

album, Out of the Cool. Nat

was impressed. Persson pointed out the name on the sleeve and they called Campi

in Cologne New York

During the

session Keg did a pretty good job, but somehow, Peck and Persson thought, he

wasn't quite matching his playing on the Evans album. After the first day's

recording was over, Persson and Peck had drinks with Johnson. They told him how

they'd heard him on the Gil Evans album. 'Some of the best bass‑trombone

playing I ever heard in my life,' said Nat Peck. 'Absolutely fantastic,'

confirmed Persson.

'Well,

thanks,' said Keg. 'But actually, that wasn't me. I didn't play bass trombone

on that album. As a matter of fact, I'm not really a bass‑trombone player at

all. I had to borrow the instrument for this date.'

The bass‑trombone

player was actually Tony Studd. But Ake and Nat took a year to break the news

to Campi.

Talking to

me about the album in November 1966 when I was preparing an article on the band

for Down Beat, Ken ny Clarke said it was one of the most satisfying dates of his

career. He said:

The record is proof positive that there are

as good musicians in Europe

as there are in the States. I have never felt that the standard in Europe

was much lower than in America Germany

I've worked around the studios in the

States and I really think that music here in Europe

is on a higher plane.

When I asked Klook how the Clarke‑Boland compared with big band of

Dizzy Gillespie he smiled the inimitable Klook smile and said, 'There is no comparison. That was the

greatest band I ever played with in my life. I have never played in a band that

was so inspirational and dynamic. It will never happen again in my lifetime.

But we can come pretty close.'

It was not

until May 1966 that the Clarke‑Boland Band played its first live concert ‑ in Mainz , West Germany Baden-Baden

The Clarke‑Boland Band showed

that musically and technically they are masters of their craft. The

compositions and arrangements were excellent and the solos displayed a

combination of vitality, a beautiful smoothness and command of musical range

... What strikes one after close listening is the classic harmony of the

brilliant soli and tutti passages, played with elegance and confidence and

distinguishing the band from all other big jazz ensembles.

Boland's

arranging style did indeed make excellent use of the soli [a section of the band playing in harmony] and tutti [literally,

“all together; the entire band or a section in unison] devices,

and they became something of a CBBB hallmark. He used them in 'Get Out of Town'

on the Handle with Care album,

and they were dramatically in evidence on the Clarke‑Boland Band's third

album, recorded in Cologne 18 June 1967 for the Saba (later MPS ) label of Hans Georg Brunner‑Schwer. For

this album, which featured Eddie 'Lockjaw' Davis Chinatown ' and called 'Sax no End'. It was a masterpiece of saxophone

scoring ‑ and it needed a saxophone team of the calibre of Derek Humble, Carl

Drevo, Johnny Griffin, Ronnie Scott and Sahib Shihab to do it justice. After

Eddie Davis solos over four choruses with just the rhythm section and Fats

Sadi's bongos, the saxophone section, masterfully piloted by Humble, plays

three complex and intricate soli choruses

with fine precision, co‑ordination and compatibility. Two roaring tutti choruses

follow. Saxophonist Ken ny Graham, reviewing the Sax

no End album in Crescendo in Mav 1968, said:

One particular bit did my old

ears a power of good ‑ a saxophone chorus brilliantly led by Derek Humble. I

just love hearing saxophones having a chance to play a well‑written chorus

instead of riffs, figures and the boosting‑up‑the‑brass chores that they

usually find themselves doing Maybe that's what Francy Boland is really all

about. Nobody does saxophone choruses these days ‑ they're not on. F.B.,

oblivious of trends etc., bungs' em in. This and similar notions of his come

off a treat because he believes in

them.

Sax

no End was a major

landmark in the band's progress towards its ultimate corporate identity and it

was followed by a number of other arrangements featuring saxophone soli, such as 'All the Things You Are',

'When Your Lover Has Gone', 'You Stepped out of a Dream', and many more. Ronnie

Scott remembers those soli passages

only too well. He says of 'Sax no End', characteristically self‑critical,

They

were very difficult to play ‑ in fact, I never really got ‘Sax no End’

down. But they were beautifully written and sounded marvellous. Derek was the

navigator in chief ‑ and, of course, Shihab was a great anchor man. After about

the first four times, he never had to look at the part.

Certainly

the arrangement made a big impression and was always a favourite at live

performances. Oscar Peterson was so taken with the chart that he actually

recorded a trio version for his MPS album Travellin' On.

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Sax no End album was

that all seven titles were recorded in seven hours.

'It was

almost always a first‑take affair when the band recorded’ Gigi Campi says. 'We

hardly ever played anything more than three times ‑ and then we usually found

that the first take was the best.'

In between

the big‑band dates Clarke and Boland made a number of sessions with smaller

groups featuring different members of the band ‑ Johnny Griffin, Fats Sadi,

Sahib Shihab ‑ and an octet album with singer Mark Murphy. The band also began

to make more live appearances, playing festivals and concerts in Germany Switzerland Austria Italy Holland , Belgium France Hungary Finland Denmark Sweden Yugoslavia Czechoslovakia Britain

Campi

worked tirelessly to project and promote the band and, recognizing early on the

importance of getting airplay for the CBBB's music, he concluded an agreement

in 1967 to sell a monthly half‑hour programme by the band to radio stations in Helsinki Stockholm Copenhagen Hilversum Brussels Vienna Zurich Baden-Baden Munich Stuttgart Frankfurt , Saarbrucken , Hamburg Berlin Cologne

The Improbability of the Clarke Boland Big Band – Part 2

© -Steven

Cerra , copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Between 1967 and 1969 the CBBB recorded a

series of fine albums, including Faces,

Latin Kaleidoscope (with Phil Woods) Fellini

7112 and Off Limits for the MPS label which were excellent showcases for

the arranging and compositional talents of Francy Boland and for the band's

exceptional 'togetherness'.

The vintage year of the Clarke‑Boland Band

was 1969 and by common consent the peak performances of the band's career were

heard ‑ and, happily, recorded ‑ during an unforgettable two‑week engagement at

Ronnie Scott's Club in London

The band broke attendance records at the

club and, says Campi, only then did the musicians really feel the full extent

of the power of which they were capable. To have the opportunity of playing

together night after night for two weeks made it possible to achieve a rapport

and a mutuality of feeling that even this intuitively integrated band had not

equaled hitherto.

By this time the CBBB had an additional

drummer. Recruiting a second drummer for a band that has Ken ny Clarke in its rhythm section would seem

to be setting a new standard in futility. But it worked. British drummer Ken ny Clare, a noted session musician, with

excellent technique and good reading ability, had first come into the band as a

sub when Klook had other commitments. He handled the job so well that he was

taken on the 'permanent staff.’ There

are various explanations as to why this happened and, in all probability ‑ as

is usually the case ‑ there is an element of truth in most of them.

Whenever it was suggested to Klook there

was one drummer too many in the band, he vigorously disagreed. Two drum-heads,

he argued, are better than one. He told Max Jones in a Melody Maker interview published on 15 March 1968 :

It

came about because of my teaching. From my experience with students

I thought that maybe drummers can play

together without being noisy or confusing. So I tried it out at the Selmer

school in Paris

Between the two of us, I

think that Ken ny

and I can play anything in the world ...

He is someone who thinks exactly the same way I do about drumming. He's

one of the most intelligent drummers I've ever met ... We're two soul brothers.

I would

suggest that this may be another example of Ken ny's tendency to retrospective

rationalization. Ronnie Scott's recollection is that Ken ny Clare's presence in the band was intended

to take some of the pressure off Klook, 'who wasn't the greatest reader in the

world. The arrangement allowed Ken ny Clarke to coast from time to time ‑ and it worked because they

were so compatible. It would have been disastrous otherwise.' And in best

Ronnie Scott style he instanced the massive all‑star band organized by Charlie

Watts in 1987 which had not two drummers but three. 'Someone asked the

vibraphone player what he thought of the tempo of a piece the band was

rehearsing. "Fine," he said, "I liked all three of them."'

They gave me a couple of notes on

vibraphone which I invariably played wrongly ‑ well, they figured that I'd

always be available to do anything that Klock wouldn't be free to do. I could

do sundry percussion. Then one number was a Turkish march thing and I played

snare drum. When it was played back it sounded very much together, like one

drummer. They talked it over. Next time I came, would I bring my drums as well?

See if we could make it with both of us playing. It worked ‑ and it's been like

that ever since.

There is no

doubt that driving the CBBB took a lot of energy and endurance and the addition

of Clare not only added to the rhythmic foundation but also spread the heavy

percussion load.

Playing

along with the greatest drummer in the world was a pretty intimidating

experience for Clare. He once told me of the first gig with Klook in Ostend

He left the

theatre after the rehearsal full of gloom and depression and decided that the

best thing to do for the sake of the band would be to slip silently away. He

went to book a flight back to London

'I started

the first number full of apprehension ‑ but from the very first beat, it all

came together miraculously. I just couldn't believe it!'

And that

was the beginning of a beautiful percussion friendship. From then on, Clare

became an integral part of the rhythm section and missed only one gig with the

band. Strangely enough, Clare said he was never able to play the same away from

the band. 'There are many drummers who would love to get the same springy kind

of beat that Klook gets. I'm one of them. When I'm with him, I can play that

way without even thinking about it. As soon as I'm away from him, I can't do it

any more.'

True to

character, Klook gave every encouragement to Ken ny Clare and undoubtedly one of the

important reasons why they worked so well together was that they had such a

warm relationship off the stage, as well as on.

British

drummer Frank King, reviewing the two Polydor albums that resulted from the

Scott engagement, wrote in Crescendo: 'The perception and telepathy

between Ken ny Clarke and Ken ny Clare is magnificent. They have such a

fantastic togetherness that in places it is miraculous.'

With Jimmy

Woode unavailable, Ronnie Scott's bassist, Ron Mathewson, was brought in for

the club engagement and with Clare, Scott, Tony Coe (on tenor and clarinet),

Humble and Tony Fisher (trumpet, depping for Jimmy Deuchar), the British

contingent in the band was as big as the American. Yugoslavia

Gigi Campi

had to miss the first week of the engagement, but when he walked into the club

on the Monday of the second week, Johnny Griffin told him, 'Gigi, you're gonna

hear some shit tonight!' Campi sat at a table with writer Bob Houston, my wife

and myself and beamed as his 'family' took the stage. ('Italians/ he'd

explained to me once, 'always try to wrap everything up in a sense of family ‑

and that's how I regard the band.') Campi had heard practically every note the

band had played since its debut. But when it hit, with a high‑voltage version

of 'Box 703

For Ronnie

Scott those two weeks were undoubtedly one of the major highlights in the

history of the club, as well as being musically inspirational. 'It was

marvellous. People used to applaud in the middle of the arrangements ‑ showing

their appreciation of some of the tutti or soli passages. It was really one of the greatest musical

experiences of my life.'

The year

1969 was certainly a banner one for the Clarke Boland Big Band. It played the

Pori Festival in Finland Rotterdam Britain

At the Prague Jazz

Festival in October, the CBBB 'totally eclipsed' the Duke Ellington band,

according to Melody Maker's Jack

Hutton: 'This year's Prague Festival proved one thing conclusively to me ‑ the Ken ny Clarke‑Francy Boland Big Band is the

finest big band in existence.’

And after a

Paris

The CBBB is a triumph, at the highest level

of talent and professionalism.

The warmth, the commitment and the

enthusiasm of the musicians is refreshing and a marked change from the

lackluster and blasé performances of the Ellington and Basie bands which we

have become used to over the last few years.

In October 1970

the CBBB was back in Britain London

There

followed a three‑week European tour which had Dizzy Gillespie as special guest

and which culminated in an appearance at the Berlin

In fact

there were now signs that the band was beginning to run out of steam and, no

doubt, one of the factors which undermined its momentum was Campi's failure to

conclude an agreement to take the band to the United States Ken ny Clarke ‑ and for all concerned with the

CBBB. But, for a variety of reasons ‑ predominantly financial ‑ plans to have

the band appear at the Village Gate in New York, followed by concerts in Boston

and Chicago, an appearance at the 1970 Newport Jazz Festival and a tour of

Canada, did not come to fruition.

'I'd really

love to take the band on the road in the States/ Ken ny Clarke told me in 1967, 'just to prove

the point about the high standard of European musicians.' But it was not to be.

What

finally caused Ken ny Clarke to acknowledge that the days of

the CBBB were numbered, however, was the untimely death of Derek Humble on 2

February 1971 at

the age of thirty‑nine. 'The band was never the same without Derek/ Ken ny said, voicing a sentiment that was

shared by the whole CBBB family.

In June

1971 the band made its last recording, Change

of Scenes, with Stan Getz as guest soloist and, in March 1972 in

Nuremberg, played its last concert date when, according to Gigi Campi, 'it was

a sorry shadow of its former self'. He went on:

Johnny Griffin USA Europe

to try to put the band together again. I called on Idrees, Nat Peck, Tony Coe

and Johnny Griffin and finished up in Montreuil

And that's

when even Campi's apparently unquenchable enthusiasm gave out. It was April

1972 and the Clarke‑Boland Big Band had breathed its last.

But, as Bob

Houston, who was closely associated with the band through most of its lifetime,

wrote afterwards, though the demise was a matter for regret, that the band had

existed at all was a matter for celebration ‑ 'as with all phenomena which

survive on excellence against the tides of current fads and fashions ... The

CBBB was one of the most enjoyable manifestations of the last decade in jazz.

Be grateful that it happened at all, and that we have it on record to enjoy.'

And Ken ny Clarke said, 'It was a fantastic, unique

experience from which I learned a lot. It was not only a great band, it was a

community, a congregation of friends ‑ and one of the happiest bands I've ever

worked with.'

The Clarke‑Boland

Big Band left a rich legacy of its repertoire on record. In the eleven years

of its existence it recorded thirty‑nine albums.

Says Johnny Griffin,

The CBBB couldn't have lasted with a Benny

Goodman or a Buddy Rich leading it ‑ because there were too many bandleaders in

the band. It wouldn't have worked if the leaders had been dictators. I mean,

the vibrations from the egos! My God, imagine ‑ three trumpet players all Leos:

Idrees Sulieman, Benny Bailey and Art Farmer. It was like an armed truce.

It was amazing with all those different characters and the strength in each

one. And it would mesh! There was no one on the band that you could pick on! It

was really like a zoo, with tigers, lions and gorillas in it!

'I never

met anyone who stayed so calm/ Ken ny Clare said of Klook in an interview with Crescendo's Tony

Brown. 'You should come along to a recording session. All pandemonium let

loose, everybody talking or blowing like a bunch of madmen. Ken ny never raises his voice or gets excited.

He is a wonder.'

Ronnie

Scott confesses that he was always a little bit in awe of Ken ny Clarke. 'But he was always so amiable

and pleasant. He didn't come on like your typical extrovert bandleader. He just

sat there, and played ‑ and that was enough.'

Gigi Campi

remembers times when Ken ny would arrive late for rehearsal or recording due to plane or

train delays. 'We would all be waiting in the studio ‑ and as soon as Ken ny walked in you were aware that there was

suddenly more power in the room. His presence ‑ quiet, dignified and calm ‑was

such a positive force.'

Jimmy Woode

says that it was simply not Klook's way to get out in front of the band and pep‑talk

the musicians. 'He might speak quietly. to you individually ‑ but his

leadership was implicit in his solid integrity. Francy and Klook were not

exactly charismatic leaders like Duke.'

Ron

Mathewson remembers Klook as a man who commanded respect from all the members

of the band without any attempt to pull rank: 'He was really helpful to me when

I came into the band for the gig at Ronnie's. He said, to me, very nicely,

"Keep a straight four. Let the guys feel you, because you're new. They

want to trust the rhythm section. Just play it cool and let it happen."'

Francy

Boland's co‑leadership consisted entirely of creating the band's inimitable

book, writing not for the instruments but for the musicians, and providing

support and solos from the keyboard that were consistently streets ahead of his

own evaluation of them. Boland carries self‑effacement almost to the point of self‑erasure.

He told me, 'Ken ny didn't really have a lot to do with the

music. And I wanted it that way because I was the arranger.'

And without

any apparent awareness of the sublime irony of a Boland being struck by someone

else's inclination to maintain a low profile, he added, 'Ken ny was a very reserved person and he kept

his thoughts to himself. He never expressed enthusiasm when I came in with a

new arrangement; though he might give me a compliment ‑ a small compliment ‑from

time to time.'

Clarke and

Boland, during their association together, were never in any danger of

engulfing one another in explicit mutual admiration. But had it not been there

in some abundance, the band simply would not have flourished. Whatever Boland

may feel about the measure of respect and appreciation he received from Ken ny, Gigi Campi remembers an incident which

speaks eloquently of Klook's high regard for his partner.

The band was rehearsing and

swinging like a demon ‑ without a drummer. Ken ny

was standing out in front, rolling a joint. Suddenly he looked up in mock

disbelief and genuine joy, and said, 'This band doesn't need a drummer. That

Belgian motherfucker swings it just with his writing, goddam it!

'For Ken ny,' Campi adds, 'there were two great arrangers in Tadd Dameron

and Francy Boland.'

Hi Steve,

ReplyDeletelistening to the track on the video my first Impression for the sax sextion was they sound like Supersax.

I also found 2 new covers in your video which adding to my list makes it now 38 Items (Hennessy mentioned 39).

Willie

Thank you very much for the information provided! I was looking for this data for a long time, but I was not able to find the trusted source..

ReplyDelete