[C] Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

"In 1989, JoAnne Brackeen was about to do a solo performance at Maybeck Hall, a small and exquisite location in Berkeley, California, with an excellent piano. She called Carl Jefferson to ask that he record it. Fortunately for the world, he did, and the resulting album became the first of a remarkable series of Maybeck Hall recordings.

The series has become a singular documentation of the state of jazz piano in our time. Carl has not-so-slowly been documenting in sound the astonishingly rich state of jazz piano as our century nears its end. He has let this brilliant body of pianists go into a sympathetic hall and show just what it is they can do when they play solo.

It is helpful to picture the room. It is not large; indeed it seats only about 50 persons. Those in the front row are very close to the player; there is no sense of distance between the performer and the audience. The room is beautifully wood-paneled and its acoustic properties are outstanding."

- Gene Lees

For some Jazz fans, solo piano is the ultimate conceit. Unbridled and unrestrained, to their ears it represents a kind of Jazz-gone-wild. Unchecked by the structure of having to play within a group, they view it as simply a vehicle for pianists to show off their techniques, or to just show-off. And unless the solo pianist is particularly adept at dynamics, tempo changes and repertoire selection, solo piano can develop a sameness about it that makes it deadly boring, to boot.

For others, solo piano represents the ultimate challenge: the entire theory of music in front of a pianist in black-and-white with no safety net to fall into. For these solo piano advocates, those pianists who play horn-like figures with the right-hand and simple thumb and forefinger intervals with the left [instead of actual chords] are viewed as being tantamount to one-handed frauds.

Can the pianist actually play the instrument or is the pianist actually playing at the instrument?

Ironically, at one time in the music’s history, solo piano was a preferred form of Jazz performance. As explained by Henry Martin in his essay Pianists of the 1920’s and 1930’s in Bill Kirchner [ed.], The Oxford Companion to Jazz [New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 163-176]:

In New York, the jazz pianist of the early 1920s was called a “tickler”‑as in “tickle the ivories.” Since Jazz was part of popular culture, the audience expected to hear the hit songs of the day, stylized and personalized by their favorite players. Often hired to provide merriment as a one‑man band, the tickler was a much‑honored figure of the era. He was wary of departing too often or too radically from the melody, since this could alienate listeners. As recordings were relatively rare and not especially lifelike, the piano was the principal source of inexpensive fun - a self‑contained party package for living rooms, restaurants, bars, and brothels. The ticklers exploited the orchestral potential of the piano with call‑and‑response patterns between registers and a left‑hand “rhythm section” consisting of bass notes alternating with midrange chords. This “striding” left hand lent its name to “stride piano,” the principal style of the 1920s." [p.163]

In particular, beginning in the 1920s and continuing well into the 1930’s, solo piano recitals by James P. Johnson, Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines, Thomas ‘Fats’ Waller and Teddy Wilson were a source of much delight and admiration for listeners when Jazz was still the popular music. Later in this period, the boogie-woogie piano stylings of Jimmy Yancey, Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, Meade Lux Lewis and Joe Turner were all the rage.

Indeed, the first 78 rpm’s issued by Blue Note Records, which was to become the recording beacon for modern Jazz on the East Coast in the 1950s and 60s, would be by Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis. The 18 performances that were recorded on January 6, 1939 singly and in duet by Ammons and Lewis have been reissued as a CD entitled The First Day [CDP 7 98450 2] and are examples of solo blues and boogie-woogie piano at its best.

Perhaps the epitome of Jazz solo piano was reached in the playing of Art Tatum, or as Henry Martin phrases it – “the apotheosis of classic jazz piano” – whose dazzling command of the instrument was a constant source of wonder and amazement to the point that some thought that they were listening to more than one pianist at the same time!

And while Erroll Garner, Nat Cole, Lennie Tristano, George Shearing and Oscar Peterson continued the tradition of solo piano into the modern era, pianist Bud Powell’s use of the right hand to create horn-like phrasing as an adaptation of the bebop style of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie transformed many pianists into essentially one-handed players in an attempt to mimic Powell’s artistry.

What’s more, over the second half of the 20th century, solo Jazz piano became something of a lost art with fewer and fewer pianists performing in this style and still fewer listeners seeking it out.

So, in the face of what had become a mostly languishing form of the art, the Concord Jazz, Maybeck Recital Hall series stands out as somewhat of an anomaly.

For not only does it revive the solo Jazz piano form, it does so in grand fashion by offering the listener forty-two [42] opportunities to make up their own mind about their interest in this genre. And, in the forum that is the Maybeck Recital Hall, it does so under conditions that are acoustically and musically ideal.

Maybeck Recital Hall, also known as Maybeck Studio for Performing Arts, is located inside the Kennedy-Nixon House in Berkeley, California. It was built in 1914 by the distinguished architect Bernard Maybeck.

"The 50-seat hall, ideal for such ventures, was designed as a music performance space by Bernard Maybeck, one of the most influential and highly revered of Northern California architects. Maybeck, who died in 1957 at the age of 95, was a man renowned for his handcrafted wooden homes in what became known as "The Bay Area Style." An architect whose principles included building with natural materials, Maybeck constructed the hall of redwood, which allows for an authentic, live sound that neither flies aimlessly nor gets swallowed up, thus making for an optimum recording environment." - Zan Stewart, Vol. 35, George Cables

The hall seats only 60 or so people, and before assuming that it’s name reflects some form of political reconciliation between the major opposing parties, the hall was designed by Maybeck upon commission by the Nixon family, local arts patrons who wanted a live-in studio for their daughter Milda’s piano teacher, Mrs. Alma Kennedy. Hence the name – Kennedy-Nixon House.

The room is paneled, clear-heart redwood, which contributes to an unusually rich and warm, yet bright and clear acoustic quality. There are two grand pianos: a Yamaha S-400 and a Yamaha C-7.

In 1923, the hall was destroyed by fire, but was quickly rebuilt by Maybeck.

The house was purchased in 1987 by Jazz pianist Dick Whittington, who opened the hall for public recitals.

In 1996, the house was purchased by Gregory Moore. The recital hall is no longer open for public concerts, although it is used for private concerts that are attended by invitation only.

Between 1989 – 1995, Whittington and Concord records produced and recorded the previously mentioned 42 solo piano, Maybeck Recital Hall performances. Each featured a different Jazz pianist and Whittington made a concerted effort to include in these recital pianists whom he felt deserved wider public recognition. In addition, Concord also released CDs of 10 jazz duets that were performed at Maybeck during this same period.

At this point, 13 years later, some of the Maybeck Recital Hall, solo piano discs issued in the Concord series may require a bit of a treasure hunt to locate, but the editors of JazzProfiles thought it might be in the interests of the more adventurous of its readers to at least make information about the complete series available through a listing, cover photo and brief annotation of each of the discs in the series.

These performances represent a all-inclusive overview of solo Jazz piano at the end of the 20th century, as well as, an excellent opportunity for the listener to make up their own mind about this form of the music as played in a more modern style.

One wonders if such an all-inclusive opportunity will exist in the 21st century or if the historical record is now closed for future solo piano recitals to be offered and recorded on this scale?

“A performance by JoAnne Brackeen, whether alone or leading a group, is an automatic assurance of authority, of energy, of adventurous originality. This has been clear ever since her career as a recording artist began. She has been making albums under her own name since 1975 in addition to notable contributions during her early stints with Art Blakey and Stan Getz. With the release of Live at Maybeck Recital Hall her ability to establish and sustain a high level of interest, unaccompanied, throughout a recording, is demonstrated with unprecedented eloquence.” ‑ Leonard Feather

Volume 2 – Dave McKenna [CCD-4410]

Dream Dancing, the first tune he played, set the tone for the afternoon. McKenna appeared, looking distracted. He seated himself, with the usual air of surprise that we'd come to hear him, and the usual "don't mind me" smile. Then the saloon cocktail player‑whatever got down to work, spinning out a melodic line, supporting it with his signature rumbling bass. In his combination of power and delicacy, he makes you imagine a linebacker who's also a micro-surgeon.

Midway through, he leaned into the keyboard and began to swing. The audience boogied in their chairs. When you’re in McKenna’s capable hands, the world goes away and you can dream, forget your troubles and just get happy.” – Cyra McFadden

Volume 3 – Dick Hyman [CCD-4415]

After all, for nearly 500 years European instrumental music has included some sort of keyboard instrument and for three of those centuries an instrument called a ..piano‑ has been accepted as the most complete of all instruments ‑ its keyboard the cry basis of musical composition. its players. more often than not, also composers.

When considering great pianists ‑ and Dick Hyman is a great pianist ‑ one should not qualify the praise by making it great jazz pianist. Hyman. like all our best instrumentalists. is a master of the piano ‑ skilled in playing, able to utilize both his astonishing physical abilities and remarkable musical mind to produce some of the grandest sounds and most distinctive interpretations to be heard in contemporary music.

Because he is a skilled composer, orchestrator and arranger in a number of musical categories. including jazz, Hyman's solo piano performances emerge as monuments to his astonishing virtuosity as a complete musician.

For more than 40 years Hyman has been an active participant on the American musical scene. as deeply involved in scores for television and film, as in recordings, jazz festivals, concert production, solo and collaborative recitals (on piano and organ) and the dozens of other areas which attract his musical curiosity.

Hyman's talents have long been known in the profession and by the jazz underground, but until the 1980s he seldom ventured out of the greater New York area as a solo performer. By the time he was hired into the Berkeley, California hills where the Maybeck Recital Hall is located, he had become immensely popular as a result of his appearances in San Francisco's "Jazz in the City"' series as well as at the Sacramento Dixieland Jubilee.” – Philip Elwood

Volume 4 – Walter Norris [CCD-4425]

“It is ironic that a pianist as vividly innovative as Walter Norris can remain obscure in the United States, and that many who know his name remember it only because he was Ornette Coleman's first (and almost only) pianist, on a 1958 record date.

Perhaps he was in the wrong places at the wrong times: in Little Rock, Ark. (home of Pharoah Sanders), where he gigged as a teenaged sideman; in Las Vegas, where he had a trio in the '50s, or even Los Angeles, where his gigs with Frank Rosolino, Stan Getz and Herb Geller did not lead to national renown.

His New York years were a little more productive. After a long stint as music director of the Playboy Club he worked with the Thad Jones Mel Lewis band, with which he toured Europe and Japan. But since 1976 Walter Norris has been an expatriate, working in a Berlin radio band from 1977 and teaching improvisation at the Hochschule since 1984. These are not stepping stones to world acclaim.

Luckily, while he was in the Bay Area a few months ago visiting his daughter, plans were set up to record him in the unique setting of Maybeck Hall, which Norris admires both for its architecture and its very special Yamahas.

"This was a very moving experience for me, "he said in a recent call from Berlin. "I had some memorable times working in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s. And Maybeck Hall is like a work of art."

That Norris can claim gifts far outreaching his fame becomes immediately clear in this stunning collection, surely one of the most compelling piano recordings of the new decade.” – Leonard Feather

Volume 5 – Stanley Cowell [CCD-4431]

“Once, recognizing Tatum in his audience at a night club, Fats Waller introduced him, saying, "I play the piano, but God is in the house tonight." Working with funding he calls a "theology grant," in 1988 Cowell developed a program of 23 pieces from Tatum's repertoire, studying the Tatum style and incorporating its essential devices into his own versions.

Cowell's improvisation is now rich with the spirit and inspiration of Tatum, perhaps the only jazz artist universally worshiped by pianists of all persuasions. In this Maybeck recital, Cowell is full of that spirit. The devices are not displayed as ornaments, but are absorbed into Cowell's approach and attitude toward jazz improvisation, which have undergone a philosophical change.

When Cowell arrived on the highly charged New York jazz scene in the sixties, he was a competitive player in those tough, fast times with their heavy freight of racial and social frustration. The urban and social revolution and the unrest and riots that accompanied it had much to do with the outlooks of many musicians in the free jazz movement. Cowell was in the middle of a branch of that movement that included players like Archie Shepp, Marion Brown, Sunny Murray, Rashied Ali and others consumed with the quest for justice. For them, the politics of the day superseded concerns with traditional, conventional values of music.

"A note was a bullet or a bomb, as far as I was concerned. I was angry," Cowell says. "But the ironic thing was that no black people ever came to our concerts; only white people. And they liked the music. So, I said, 'wait a minute, this is stupid; what are we trying to do?' I just felt that I was misdirecting my energies. I, and eventually all of these players, went back to dealing with the tradition, the heritage of jazz and other music. We looked for more universal qualities ... beauty and contrast, nonpolitical aspects. Ultimately, music is your politics anyway, but you don't have to be one‑dimensional about it."

Beauty and contrast abound in the music at hand. And, to clearly stake out the pianistic territory from the start, Cowell gives us technique in the service of beauty and contrast.” – Doug Ramsey

Volume 6 – Hal Galper [CCD-4438]

“This concert at Maybeck Recital Hall took place at a pivotal moment in Hal Galper's life. It was the last week of July, 1990. After ten years, he had just left The Phil Woods Quintet. His first performance after that departure was this solo concert and recording.

"I was approaching it with a perfectionist attitude, like I had to have everything worked out. And I was getting more and more uptight about it. So I threw all my plans out the window! I went in with 20 or 25 songs that I had sort of done things on, and I winged it!.

For somebody who's been in the rhythm section of one of the world's best bebop groups, this is a lot of adventurous piano. "I realized that nobody's really heard me play!" says Hal. "I've been accompanying guys for 30 to 35 years, but basically I've been watering myself down as a professional accompanist. So I decided to throw the professionalism out the window and to say what I want to say musically." – Becca Pulliam

Volume 7 – John Hicks [CCD-4442]

John Hicks had heard of Maybeck Recital Hall long before he made his debut in the intimate room in August, 1990, to record this, his first solo piano album. JoAnne Brackeen, whose Maybeck album launched this quickly expanding and unprecedented series of solo piano recordings, had raved about the place to Hicks. When he sat down to play, he felt right of home.

Maybeck isn't on the map of usual jazz hot spots, but on a narrow, winding residential street in the Berkeley hills, near the University of California campus. Inside, it doesn't resemble a jazz club either Designed, as it's name implies, as a recital hall for pianists (the classical variety) 80 years ago, it was used mostly for private affairs. Since Berkeley school teacher Dick Whittington and his wife Marilyn Ross bought it a few years ago, they have staged weekly concerts, mostly solo, occasionally classical, but more often with some of the finest improvisers in jazz.

Because Maybeck holds only 60 listeners, musicians come not to make money so much as to have that rare opportunity to play what they want to, for an audience open to new sounds.

The high‑ceiling performance space is made almost entirely of natural wood, much of it handcrafted by architect Bernard Maybeck's builders. That sense of human touch and care gives the room its ambience, one that leads musicians to play music that is at times spirited, at others spiritual. The recordings that have come out of Maybeck on Concord Jazz are proof that the muse of the improvising pianist has had direct contact with the artists who have performed there.

Unlike most of the recordings he has made under his own name (ones that feature his compositions), for the Maybeck date, Hicks said, "I wanted to do some more standard compositions. Playing solo gives me a chance to extend my repertoire and play some songs I don't normally play in a group setting. By myself, I can take them in directions you just can't got to when there are other musicians involved.

"For Maybeck," Hicks said, "there were certain things I wanted to record, but really the recording aspect was incidental to the performance. I arrived with a list of songs I wanted to do. But once I started, I picked songs based on the feeling I got from the audience.” – Larry Kelp

Volume 8 – Gerald Wiggins [CCD-4450]

“Wig ... I love this album.

Wig and I have been friends since the early 40s. I've respected his talent and listened to him grow ever since. Of course, in the business, you aren't in close contact unless you live in New York (where you meet on the street more often). Out here in LA it is very spread out and sometimes hard to go see other musicians.

I've always loved Wig's playing for several reasons. First of all, he doesn't take himself too seriously. To do that is a big mistake ... I've learned from experience. He also enjoys playing good songs. He has fun when he's playing. Music is really about having fun. If not, why do it? You study hard, then have fun using what you've learned. And ideally, you make money doing what you love to do.

Wig has another great quality, natural relaxation. Art Tatum had it, and it shows in Gerald. (They were good friends.) That is one of the most important things in playing. It has its effect on people and they enjoy it without realizing why. That goes for both the audience and musicians alike and is one of the reasons everyone enjoys playing with Wig.

Wig is respected because he has all these qualities plus a beautiful touch and he never overplays.” – Jimmy Rowles

Volume 9 – Marian McPartland [CCD-4460]

“The night before she was scheduled to play the ninth jazz piano concert recorded for the "Live At Maybeck Hall" series, Marian McPartland sat down at the Baldwin in her hotel room, not far from the concert hall on a hill, and toyed with a few tunes. She had a long list ranging from standards written in the 1920s and 1930s to an offbeat, rollicking blues by Ornette Coleman and also a whirling improvisation of her own ‑ "the kind of modernistic things I like," she says of the latter songs. She headed toward the concert hall in high spirits, because she knew she would have a good audience in a wonderful, small hall with a nice piano. But she still hadn't decided what to play. "Well, play this thing," she told herself. "It's all going to work out."

Miss McPartland brought her characteristic strength and classiness to each tune. To her fastidious technique, forceful sound and emotional depth, add her ‘au courant’ imagination and far‑ranging intellectual curiosity about all musical material, and you will arrive at some conclusions about why her concert, which she programmed intuitively on the spot for her audience, turned out to be a standard – a vision – for great jazz piano.” – Leslie Gourse

Volume 10 – Kenny Barron [CCD-4466]

“Kenny Barron has been playing piano out there for two thirds of his life. This son of Philadelphia began work barely out of high school, partly through his late brother Bill’s solicitude. Kenny played with homeboy Jimmy Heath and Dizzy Gillespie in his teens, Yusef Lateef and Ron Carter in his thirties, sax‑man Bill often. In recent years he’s co-founded the Monk‑band Sphere and duetted prettily with romantic soul‑mate Stan Getz.

Nevertheless, opportunities to attack the keyboard all alone are (blessedly?) rare‑ even gigs at Bradley’s have room for a bass player! Flying solo challenges a pianist. "It’s difficult for me," admits Barron: ‑ "this is only my third solo album." Barron approached this recital as a chance to expatiate on personal history; he plays jazz etudes, pieces which focus on specific aspects of the music. Some glance back to acknowledged influences (Art Tatum, T. Monk, and Bud Powell), some explore his present trends. The excursion exposes Barron’s deep roots in bebop and flourishing Hispanic traces, and establishes a tenuous balance between relaxation and tension.” – Fred Bouchard

Volume 11 – Roger Kellaway [CCD-4470]

“Roger Kellaway and I have been writing songs together ‑ his music, my lyrics ‑ since 1974. I've known him since 1962, when he played piano on the first recording of one of my songs.

When you write with someone, you get to know how he thinks. Roger and I influenced each other profoundly, attaining a rapport that at times seems telepathic.

Contrary to mythology, most jazz musicians have always been interested in 'classical" music, adapting from it whatever they could use. This is especially so of the pianists, almost all of whom had solid schooling in the European repertoire. But Kellaway has gone beyond his predecessors.

He is interested in everything from Renaissance music to the most uncompromising contemporary ‘serious’ composition, and all these influences have been absorbed into his work. While a few other jazz pianists have experimented with bi-tonality, and even non-tonality, none has done it with the flair Roger has. Roger respects the tonal system as a valid language that should not be abandoned, and recognizes that the audience is conditioned to it, comfortable in it. When he ventures into bitonality (and he began doing so when he was a student at the New England Conservatory, thirty‑odd years ago), he does so with an awareness that he is making the listener "stretch." And he seems to know almost uncannily how long to keep it up before taking the music, and the listener, back to more secure terrain. Roger, furthermore, has a remarkable rhythmic sense. He can play the most complicated and seemingly even contradictory figures between the left and right hands of anyone I know.

The independence of his hands is marvelous. He is himself rather puzzled by it. All this makes for an adventurous quality. It is like watching a great and daring skier.

There are two other important qualities I should mention: a whimsical sense of humor and a marvelously rhapsodic lyrical instinct, both of which inform his playing, as well as his writing. His ballads are exquisitely beautiful.” - Gene Lees

Volume 12 – Barry Harris [CCD-4476]

“When Barry Harris' name is mentioned, other pianists usually react with awe. This is esteem which has been earned over a lifetime of making exquisite music; since he was the house pianist at Detroit's Blue Bird Club nearly 40 years, Harris has commanded the stature and respect due the consummate artist.

He has granted a NEA Jazz Masters Award in 1989, and his eclectic talents and versatility are probably best illustrated by the fact that he has also composed music for strings ….

Often viewed as the quintessential bebop pianist, his playing does maintain the tradition of Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. However, his consistency, grace, energy, and style transcend the bop idiom. Barry Harris' approach is polished and insightful, and there is a humanity and warmth in his music that truly touches the heart, even when he's playing at a breakneck tempo.

He is also a highly respected educator, who travels around the world performing and giving intensive workshops (he was in Spain, on his way to Holland at the time these notes were written). Students flock to Harris wherever he is because of his talent and reputation and his singular ability to communicate. He enjoys the teaching process, and conveys that spirit and his love of music directly to his students.

That same spirit is clearly evident in his playing, and never more so than at this concert at the Maybeck Recital Hall. His first recording on the Concord Jazz label, it shows the full spectrum of his talents, highlighting the softer, introspective side of his art with numerous ballad interpretations as well as displaying the electrifying speed with which he can construct a magnificent solo (no one can carry the furious pace of a bebop chase with more aplomb).” – Andrew Sussman

Volume 13 – Steve Kuhn [CCD-4484]

Kuhn's last solo piano album was the 1976 studio recording, "Ecstasy." Live at Maybeck Recital Hall is his real coming out as a solo pianist, a perfect showcase in a warm and intimate room, with a packed house and the complete freedom to play whatever he felt.

"At Maybeck, I had a list of 25 or so songs, but I didn't know what I'd play until I sat down and started." Even then, while the tune itself may be fixed as to basic melodic and harmonic structure, Kuhn reinterprets the piece depending on the spirit of the setting and moment. "Each time I've performed these tunes, I've played them differently. And when I play alone, they can change drastically."

The one constant in the Maybeck series recordings is owner Dick Whittington's introduction of the pianist. From there the artist takes over, often revealing facets and depths of inspiration unheard of in previous group recordings. That's the beauty of this series, taking both well‑known and less familiar pianists and giving them free rein to create.

Solar is composed by Miles Davis. "I heard it in 1954 on Miles'recording with Kenny Clarke and Horace Silver. It was structurally unusual at the time. A 12‑bar form, but it's not a blues. Rather than a harmonic resolution on the final bar, it goes right into the next chorus... a sort of circular form. And, it's got a dark, somber mood to it, I do it with the trio; it's a good vehicle for improvisation."

It's also a good example of how Kuhn reworks a tune to fit his own style. He begins with a one‑hand, single‑line introduction, and slowly works into the actual tune, the spareness adding an austere, lonely feel. Then he picks up to almost swing tempo for the midsection, eventually taking off with a fast‑walking left‑handed bass line, while the right hand romps all over the harmonic structure, then shifts down for a more thoughtful conclusion.

Although it's easier to discuss how he leaps over preconceived notions of song forms, his uniqueness stems from his ability to draw the listener into a specific feeling or mood, gradually running the emotional gamut. It's the overall experience, not just the beauty of the playing, that makes Kuhn's performance memorable.” – Larry Kelp

Volume 14 – Alan Broadbent [CCD-4488]

Alan is a superbly lyrical talent, whether in his incarnations as arranger, composer or player. I am very drawn to such artists. They speak to me in voices I crave to hear. They are about gentleness and love and compassion. We need them in a world groaning under the burden of ugly.

"I feel," Alan said, "that jazz is first of all the art of rhythm. I might have a particular musical personality that comes through, but for me it has to emanate from a sense of an inner pulse. Everything I play is improvised, so as long as my melodic line is generated by this pulse, my left hand plays an accompanying role that relies on intuition and experience as the music demands. The apex of this feeling for me is in the improvisations of Charlie Parker. Regardless of influences, he is my abiding inspiration, and it is to him I owe everything."

The piano occupies a peculiar position in jazz and for that matter music in general. It is inherently a solo instrument. It can do it all; it doesn't need companions. In early jazz, when it came time for the piano solo, everybody else just stopped playing. Later Earl Hines realized that part of what the instrument can do has to be omitted if it is to be assimilated into the ensemble. You let the bass player carry the bass lines and let the drummer propel the music. Hines had great technique, but deliberately minimized it when playing with a rhythm section. So did Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Mel Powell, and all the other good ones.

When bebop arose, the common criticism was that the new pianists had "no left hand." So to prove this wrong, Bud Powell one night in Birdland played a whole set with only his left hand.

Alan is, at a technical level, an extraordinary pianist. He is a marvelous trio pianist, but like all pianists, he necessarily omits in a group setting part of what he can do. This solo album permits him to explore his own pianism in a way that his trio albums have not. And to do so in perfect conditions.” – Gene Lees

Steven Cerra [C] Copyright protected; all rights reserved

Paul Berliner in his Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994] underscores the point that:

“As the larger jazz tradition constantly changes, certain junctures in its evolution generate turbulence in which artists reappraise their personal values, musical practices, and styles in light of innovations then current.” [p.276].

No where in Jazz is this more true than in piano styles which evolved from the orchestral Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller to the stride of James P. Johnson and Luckey Roberts to the octaves and tremolos of Earl Fatha Hines to the boogie woogie rumblings of Jimmy Yancey and Meade Lux Lewis to the single note melodic runs of Count Basie and Teddy Wilson to the horn-like bebop phrasing of Al Haig and Bud Powell to the block chords of Milt Buckner to the octaves apart single note lines of Phineas Newborn, Jr. and to the post bop chordal and modal innovations of Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock, respectively.

Along these way, these stylistic transitions or “new ways of improvising raise the passions of advocates and adversaries alike, causing a realignment of loyalties within the jazz community.” [Berliner, p. 277].

Some follow into the new styles while others “… remain largely faithful to their former style, continuing to deepen their knowledge and skill within the artistic parameters they had defined for themselves.” [Ibid.]

As Tommy Flanagan shares in Berliner:

“What Herbie and Chick did was just beyond me. … It was something that just passed me by. I never bothered to learn it, but I love listening to it.” [Ibid.]

The Maybeck Recital Hall/Concord series provides the listener with the chance to explore all of these stylistic options in the context of solo piano: are new movements being incorporated into older styles; does the artist seem to value change or does tradition seem to prevail; is the artist experimenting and exploring or does the artist display a singularity of vision in his/her improvisational approach?

To continue the Treasure Hunt metaphor that is part of the initial theme of this piece, but place it in another context, the listener also gets to search out in the music on these recordings how solo Jazz piano has stylistic evolved in the second half of the 20th century.

All of us are far richer because Dick Whittington of the Maybeck Recital Hall and Carl Jefferson of Concord had the wisdom and the courage to make these solo piano recordings.

And besides a great grouping of Jazz pianists playing solo in a fantastic setting, the series also makes available the insightful and instructive insert notes written by the likes of Gene Less, Doug Ramsey, Leonard Feather, Jimmy Rowles, Burt Korall, Willis Conover, Grover Sales and Don Heckman to enrich the listener’s appreciation of the music.

Volume 15– Buddy Montgomery [CCD-4494]

For the past several years, Montgomery has spent significant amounts of time playing a regular hotel gig in New York City; the fruits of that work are evident here, not only in the intriguing historical range of material, from Fletcher Henderson's Soft Winds to Gwen Guthrie's This Time I'll Be Sweeter, and from melodies that are thoroughly ingrained in the popular consciousness (Since I Fell For You, The Night Has A Thousand Eyes, What'll I Do) to challenging originals (Who Cares, Money Blues), but especially in the sure and sensitive way that he creates moods and sculpts sound.

Montgomery's romanticism can be heard in his almost rhapsodic approach to such ballads as Something Wonderful and You've Changed, and an abiding traditionalism emerges in his deliberate use of his left hand, with occasional faint echoes of Harlem stride. But just as prevalent are the modernism of his harmonic choices, the judicious use of space and silence, and a wonderful unpredictability in his intermingling of two handed styles (the variations on A Cottage For Sale, for instance), his shifts from dramatic block chords into rippling arpeggios, wry infusions of blue notes, and spare, effective use of lean single note runs. (The compact disc is graced with a little more of everything through the eclectic treatment of The Man I Love, the warm meditations on How To Handle A Woman, and the many moods of By Myself.) - Derk Richardson

Volume 16– Hank Jones [CCD-4502]

"Maybeck Hall is unique," said Hank Jones. "I was amazed at the sound, the presence. It's a small room, and yet you get that cathedral sound - the acoustical properties are truly fantastic. And the piano, of course, was in excellent condition." So, I might add, was Hank Jones.

Hank Jones has been a central piano figure on the world scene for close to a half century; I had the pleasure of introducing him on records, as a sideman in a 1944 Hot Lips Page date. He was the eldest of three brothers: Thad Jones followed him on the path to fame, as a Count Basie sideman, from 1954. Two years later Elvin Jones moved from Pontiac, Michigan, the brothers' home, to New York, where he became a member of the Bud Powell Trio.

Hank, like most other pianists of the day, was strongly impressed by Bud Powell, but like Tommy Flanagan and others from the Detroit area, he transcended the bop idiom to become an eclectic interpreter of everything from time-proof ballads to swing and bop standards.

"I don't want to sound dogmatic," Hank said recently, "but in my opinion the greatest songs were written in a period between about 1935 and 1945. A lot of the finest writers are no longer around."

Over the decades Hank Jones has recorded in a multitude of settings, from small combo dates to big bands to accompanying Ella Fitzgerald and other singers. However, all that is needed for a complete demonstration of his singular artistry is a well conceived repertoire, fine acoustic conditions, and a piano worthy of him. On this occasion Hank blended these three elements into what is undoubtedly a highlight in the fast-growing and invaluable Maybeck Hall series. – Leonard Feather

Volume 17– Jaki Byard [CCD-4511]

I first heard Jaki Byard in the summer of 1940 at a storefront saloon called Dominic's Cafe in Worcester, Mass. I was a high school freshman studying classical piano, but getting distracted by that other, earthier sound. The word was out among professional and aspiring swing musicians around town: Drop by Dominic's; there's an 18-year old kid on piano who does it all.

The club door was open to the humid night and what poured out was a jubilant, cocky, articulated sound that leaped and shouted and drew me in. The pianist, big and heavy-shouldered, was sitting a ways back from the keyboard, looking down at it fondly as his fingers dug in. I sat in a corner of the funky little club and listened for two hours with a goofy grin on my face.

A week later I had deserted Bach and Chopin and was studying with Jaki. He became the sole bright flame by which local pianists could warm and nourish themselves, and we all suspected he wasn't long for Worcester. We were right. By his mid-twenties there seemed nothing he couldn't do on piano, and he soon gravitated, via Boston, to New York, where he knocked out session players with his prodigious two-handed command and began his association with the more adventuresome of the modernists: Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus and Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

It's all here, the lyrical and the rollicking, the finely-tuned comic flair and roving, impish imagination filtered through a bedrock sense of swing and surpassing technical command. For those who haven't heard Jaki Byard before - I can't imagine there are many - this album will serve as an introduction to perhaps the most resilient and resourceful pair of hands in the business. – Don Asher

Volume 18– Mike Wofford [CCD-4514]

Here is yet another presentation in what are already being referred to as "historic" Maybeck Recital Hall recordings. This array by Mike Wofford is at once riveting and delicate, powerful and sensitive, humorous and serious. "I wanted this recital to be a personal statement, an honest expression, and to be as spontaneous as possible," Mike commented.

Wofford interweaves many elements of piano history throughout his program. Listen for snippets of stride, for example, in Too Marvelous for Words, or his approach to the semi classical Impresiones Intimas No. I by Spanish composer F. Mompou.

His high regard for other pianists is evident in his selections of Ray Bryant's funky Tonk and Bill Mays' For Woff (composed with Mike in mind) and One to One. Unintentionally, Wofford chose six of his twelve selections from the decade of the 30s, offering a diverse spectrum of styles: Impresiones Intimas No. 1, Little Girl Blue from the movie Jumbo, Too Marvelous for Words from the movie Ready, Willing and Able, Rose of the Rio Grande, Topsy, and Lullaby in Rhythm. Duke Ellington's slightly later Duke's Place (42) is also known as "C Jam Blues" and Mainstem ('44) has gone by other titles, such as "Altitude," "Swing Shifters," "Swing," and "On Becoming A Square."

In a 1980 Piano Jazz radio interview with host Marian McPartland (another Maybeck Recital Hall pianist, Volume 9), Oscar Peterson said, "I think that most pianists are ambidextrous, in their thoughts anyway. If you're accompanying yourself ... there are two separate lines going. Regardless of the simplicity, there is split thinking there. You just increase that split thinking to your own particular needs." This is particularly true of Mike's playing throughout this entire recording, and especially arresting in Stablemates and in Rose of the Rio Grande. – Jude Hibler

Volume 19– Richie Beirach [CCD-4518]

More than just a concert recording, Beirach's performance at Maybeck is a snapshot of the artist in a moment of creation. Not yet an elder statesman, but no longer a newcomer to the world of jazz, Beirach stands now at a plateau, from which he can look back on the traditions that defined his early development - the textural genius of Miles Davis, the technical rigors of European classical repertoire, the probing harmonic imagination of Bill Evans - while also mapping the horizons of his own distinctive style.

From the opening notes of All The Things You Are, his method is clear: Whether playing standards, original tunes, or free improvisations, Beirach considers the essential structure of each piece much as a chess player ponders the positions of his pieces. Where can this phrase lead? How can this chord be expanded in a way to suggest different perspectives on a well-known theme? On the next cut, On Green Dolphin Street, the same approach applies, though here the question involves expansions of the melodic concept over an intentionally spare harmonic base: With the left hand restricted to playing two notes, an open fifth, how far can the right hand stretch without disrupting the implied chord changes? Answer: In Beirach's hands, far.

Each cut on this album offers, in its own way, another lesson on how a profound musical intellect can transform well-known material into fresh and highly personal artistic statements. All Blues swings with a vengeance, Some Other Time eulogizes the classic Bill Evans interpretation, Spring Is Here brilliantly amplifies the harmonic suggestion of the motif, and Elm is a feather in the air, breathlessly suspended.

Yet all of it bears Richie Beirach's imprimatur - passion tempered by discipline, exhaustive analysis in order to give the seeds of his inspiration their most fertile settings. More than most pianists, Beirach has mastered these paradoxical aspects of creativity. That they survive on this album is his credit, and our good fortune .- Robert L. Doerschuk

Volume 20– Jim McNeely [CCD-4522]

McNeely singles out Getz as a primary influence: "He showed all the people who worked with him, by example, how to develop and shape a solo, how to give it a sense of content." The pianist credits Mel Lewis as his "time" guru. "I learned a lot about time and the pulse from Mel," McNeely says. "Just being around him helped; he was very giving."

It is curious to note, considering his ample technique, McNeely has had no formal "classical" training as a pianist. However, he has always thought a great deal about "tone," what colors you can extract from the piano. Unlike most pianists, he sometimes uses drum exercises during practice sessions. For as long as he can remember, he has been fascinated with the rhythmic aspects of his instrument - this is everywhere apparent in this recital. Rhythms basic to other cultures - i.e. Africa, Indonesia - are a continuing interest. His training as a composer also has been a factor in the directions he has taken as a pianist. The act of composing, a major aspect of jazz improvisation, activates his ever-developing sense of color and progressively increases the diversity, range and subtlety of his piano work.

"The first pianist who had an effect on me was Wynton Kelly," he says. "I loved the fluid swing of his lines. His great strength was as an accompanist, both for players and singers."

You can hear love and respect for piano genius Art Tatum in McNeely's playing. "Art Tatum looms over you," he explains. "Like Parker and Coltrane, he remains a formidable force, setting an example for pianists and all musicians, for that matter. Arnold Schonberg had that kind of hold on composers earlier in this century." He paused then continued: "You either follow in the path of the great inventor or consciously try to avoid his influence."

In McNeely's case, it's been a matter of weighing and evaluating what he learns from others, assimilating what is best and most functional for him and using it his own way. This applies to Tatum and all those who have helped shape him - from George Wiskirchen, his band director at Notre Dame High School in Niles, Il.; to the ubiquitous Thelonious Monk; to such other pianists as Herbie Hancock and McCoy Tyner - the latter two defined by McNeely as "the post-boppers who helped create a new harmonic language." – Burt Korall

Volume 21– Jessica Williams [CCD-4525]

It's all there in the first track. Within a few choruses, Jessica Williams shows her hand, or hands: the harmonies in seconds (hit way off to the side of the piano), the punchy attack, the dust-devils in the upper octaves, the nutty quotes. it's familiar Jessica, but she's got plenty up her sleeve for the rest of this remarkable entry in the Maybeck menagerie.

She came to my awareness as a word-of-mouth legend, a Baltimore-bred genius whose history and personality were said to be as mysterious and unpredictable as her keyboard inventions. As soon as I got to hear her, I was into the reality of her spontaneous magic and not much concerned with the legend.

Williams impressed a bunch of visiting virtuosi as house pianist at the long-lamented original Keystone Korner in San Francisco's North Beach. Her recordings from the late '70s and early '80s confirmed her technical and compositional skills for her followers and a few new converts (including kindred spirits and album contributors Eddie Henderson and Eddie Harris).

But she remained a best-kept secret of the Bay Area and Sacramento, her long-time home, commanding awe and quiet in the clubs she visited alone and with her most consistent trio-mates, bassist John Wiitala and drummer Bud Spangler (who helped engineer this current project).

Aside from the first offering, you'll find several other standards that have been earlier treated by Monk. Although Williams echoes the past master's kinky intervals, "wrong" notes, and swaggering stride, she plays around more than he did with time and with all parts of the piano, extending her long arms to strum the strings from time to time.

She's also more concerned than Monk and many jazz pianists with keyboard technique, from barrelhouse trills to cascading Chopinesque runs. As the critics have noted, Williams is a very physical player.- Jeff Kaliss

Volume 22– Ellis Larkin [CCD-4533]

Ellis Larkins has long been a venerable member of that exalted breed that Basie dubbed "the Poets of the Piano," a special class that includes Roger Kellaway, Alan Broadbent, Jessica Williams, Walter Norris ,Adam Makowicz, Jaki Byard, Jim McNeely, and others recorded by Concord’s Maybeck Series These pianist-composers are distinguished by their ability to sustain a solo program without the support of bass and drums, by a keyboard prowess as thorough as that of any classical pianists, and by an eclecticism that embraces the standard ballads, bebop, and the legacy of Earl Hines, James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk.

They are sometimes known as "pianist's pianists," that polite way of describing a towering but inadequately recognized talent. Until Concord, few had recorded for a major label, and few if any were known outside the clan of musicians, critics and jazz lovers. None have been more unjustly overlooked than Ellis Larkins, and few have been as long honing their art.

One of John Hammond's innumerable discovery-proteges, Baltimorian Ellis Larkins, fresh from Juilliard, made his professional debut in 1940 at Cafe Society Uptown at age 17 to make an instant impression on Teddy Wilson, Hazel Scott and other fixtures at Barney Josephson's mid-town Manhattan showcase. For the next half century his delicate-yet-firm classical touch and springboard beat put him in demand in the recording studios with Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Sonny Stitt, Edmund Hall, Ruby Braff, and most of all, the singers: Mildred Bailey, Sarah Vaughan, Maxine Sullivan, Anita Ellis, Chris Connor, Helen Humes, Joe Williams, and Larkins' "particular favorite to work with," Ella Fitzgerald.

Leonard Feather's Encyclopedia of Jazz hailed Larkins as "a favorite of virtually every singer he has accompanied. His articulation is exceptionally delicate, and his harmonic taste perhaps unmatched in jazz." Bill Evans' manager-producer Helen Keane told Gene Lees: "When I was booking talent for the Garry Moore Show, I would cringe with apprehension whenever a new, unknown singer would come in to audition with Ellis Larkins, because I'd have no way of knowing whether that singer was any good or not." …

Carl Jefferson of Concord Records deserves our thanks for rescuing the likes of Ellis Larkins from the relative obscurity of the minor labels, to bring these Poets of the Piano to the larger audience that is rightfully theirs.” - Grover Sales

Volume 23– Gene Harris [CCD-4536]

When Count Basie died in 1984 he took with him the rarest of piano skills - that is, the ability to play and sustain a blues groove, regardless of tempo, using as many or as few notes as the moment inspired. Basie understood implicitly the minimalist underpinnings of great art, that addition by subtraction is key to the process of crafting powerful statements.

Of the many pianists who have followed Basie's stylistic guidelines, Gene Harris may be closest in spirit to the great bandleader. He possesses a refined touch and timeless sense of drama, borne from the desire to let his music unfold and reveal itself naturally, organically, like a flower opening to light.

On this, volume twenty-three of Concord's Maybeck Recital Hall series, Harris gets a chance to be his own band, to wax full and orchestral. Note, for instance, how thoroughly he deploys his left hand on Blues For Rhonda, eagerly matching his bass bottom walks with sprightly offerings from on high. He recognizes the fundamental infectiousness of stride, especially here, where he colorizes his blues with modern trimmings.

But to offset the notion that his métier implies only the blues ‘n’ boogie, Harris provides some melody-rich readings of songbook standards.

That he chooses for scrutiny the evergreens old Folks, or My Funny Valentine, or Angel Eyes, underscores the breadth of his talent. His treatment of Valentine, in particular, with its surprising quote from "The Greatest Love of All" (a minefield of unchecked sentimentality in less skilled hands) aligns perfectly with Maybeck’s innate loftiness and generosity of spirit.

That should be no surprise, for Harris has the ability to tap his surroundings, to concede music's great power and permit it to flow through him.- Jeff Levenson

Volume 24– Adam Makowicz [CCD-4541]

“Adam has chosen well. May he do it again. Soon.”

I wrote those words about Adam Makowicz and the music he chose to play for his previous record. Thank God and Carl Jefferson (not a redundancy) for this new performance of music Adam has chosen to play.

A few more words about Adam are repeated here: His name is pronounced "ma-KO-vitch," not "MAK-o-wits." And: Adam told me he had been studying classical music at the Chopin Secondary School of Music in Krakow, Poland, when at the age of sixteen he heard my Voice of America broadcast of Art Tatum playing piano. Immediately, he said, he decided to become a jazz pianist.

Among the musicians who visited nightclubs to see and hear Art Tatum were George Gershwin, Vladimir Horowitz, David Oistrakh, and Sergei Rachmaninov. Tatum said, "Rachmaninov once told me, 'Mr. Tatum, I can play the same notes you play, but I cannot maintain the same tempo."'

Today, Adam Makowicz does what few pianists dare: he makes Tatum his standard. Not his model. While he acknowledges his teachers, school's out.

All alone at a piano, Art Tatum was an orchestra. So is Adam Makowicz. Willis Conover

Volume 25– Cedar Walton [CCD-4546]

In the course of a distinguished career, Cedar Walton has been heard mainly in a variety of instrumental settings - most notably with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers in the 1960s, with the Eastern Rebellion group in the '70s, and with the Timeless All Stars in the '80s. He has toured the USA, Europe and Japan leading his own trio. All these activities may have obscured the fact that Cedar's piano talent is totally self-sufficient, as this Maybeck Hall session makes vividly clear.

"This is a wonderful place to record," Cedar says. "The hall is unique, with two Yamahas that are kept in top shape, and an intimate ambiance. I thought I'd relax and warm up in front of the audience by just playing the blues." On this opening cut, The Maybeck Blues, Cedar starts out on a slightly old-timey note but soon moves into a more contemporary groove with boppish left hand punctuations. This totally improvised performance at once establishes Cedar's mastery of the art of swinging and creating without accompaniment.

All the compositions in this live - very live - performance have some special meaning for Cedar. Sweet Lorraine, for example, is a tune he has always admired but never got around to recording previously. He remembers it mainly from the Nat King Cole version, though he probably also heard Art Tatum help convert it into a jazz standard. …

Much as I have admired Cedar Walton's work over the years in many different contexts, the experience of hearing him on his own - and particularly on a fine piano in this elegant setting affords a very special pleasure, adding a lustrous plus to the long and consistently successful series that Maybeck Hall and Concord Jazz have made possible. - Leonard Feather

Volume 26– Bill Mays [CCD-4567]

Elastic imagining distinguishes one musician from another. Stretching musical ideas to fit his own interpretive loom is accomplished so frequently by Bill Mays that he could become another definition of 'amazing' and have it spelled 'a-MAYS-ing!'

In the inveterate historic Concord Jazz Maybeck Recital Hall recordings, Bill Mays' Volume 26 sets forth a blistering standard of excellence. Included are two original songs: Boardwalk Blues and Thanksgiving Prayer, plus an array of ten other tunes that bounce with vitality. Mays dents and fattens notes until they enter an altered, but recognizable state, leaving no doubt as to either the song title or to the man who created that particular rendition.

Bringing diversity to his playing with contrasts ranging from stride to bebop, from spirituals to swing, Bill Mays is never at a loss for interesting pianistic statements. He evokes emotions which can move the listener to tears, to laughter, or to any other mood he creates. His sense of time and his inquisitive mind take him into depths of sounds so inventive that one wonders how he will find his way back to the point of origin. Not to worry. His musical journeys are at once fascinating and fulfilling.

"The audience at Maybeck is wonderful. They are up for it. They are very quiet and appreciative; the piano is excellent. The acoustics are just about perfect. All that wood. Boy," he concluded.

And all that Bill Mays. Boy! - Jude Hibler

Volume 27– Denny Zeitlin [CCD-4572]

Andre Gide once wrote that all great art has great density - whether it occurs in the loony antics of Fritz the Cat, the deceptive simplicity of a Mozart melody, or the textural complexities of a Shakespeare drama.

Solo performance has always been the vehicle of choice for uncovering a jazz pianist's true creative densities. Unlimited by the need to follow any musical path other than their own, most pianists revel in the opportunity to explore the outer limits of their skills.

There is no better example than Denny Zeitlin. Typically, for a man whose career has been devoted to a pursuit of the elusive fascinations of music and the mind, pianist/psychiatrist Zeitlin was delighted to perform a solo program at a Maybeck Recital Hall concert. It was, for him, a unique occasion in which to display the symbiotic connections between both disciplines.

"The great excitement in solo piano playing, for me, is in being the only person there," said Zeitlin, "-in knowing that my task is to usher myself into a merger state with the music itself and with the audience.

"I think there are fluctuating states of consciousness that people get into when they perform, and the one that feels most successful to me is when I can have a sense of the music sort of coming through, almost as though I'm a conduit for the music. If the audience accepts the invitation to participate in the merger state, then a special rapport occurs. And when that happens, then - as a solo pianist, in particular - I just feel as though I'm in the audience listening to the music."

Zeitlin clearly did a great deal of interactive listening in this performance. Not only are his improvisations inventive and varied, as might be expected, but they also reveal a remarkable integration of his myriad musical experiences - from bebop in the fifties, to avant-garde in the sixties, electronics in the seventies, and eclectic free-grazing in the seventies and eighties. Just past his 55th birthday, and after twenty albums and many decades of international touring, Zeitlin has achieved the status of creative elder, gathering together his nearly 40 years of seasoning into a mature, richly textured, esthetically dense musical expression.

The concert included originals and standards. "The program" said Zeitlin, "sort of coalesced over a few weeks of just thinking about what I'd like to do, and browsing through my record collection with the idea of finding what would be exciting and challenging.

"I wanted to present some aspects of the whole range of my interests. I knew it wouldn't be tilted toward the avant-garde, but I also felt that it would be alright to include a little dissonance as well."

And the dissonances are there, in fact - but never for their own sake, and always either as piquant sprinklings of spice or as dramatic, attention-getting dashes of pepper. – Don Heckman

Volume 28– Andy LaVerne [CCD-4577]

If we were to trace the evolution of jazz piano, the line would begin in the realm of rhythm, where Jelly Roll Morton, Fats Waller, and the early giants laid the foundations of swing syncopation. From there, it would wind into melodic territory; here, such players as Earl Hines, Nat Cole, Bud Powell, and Erroll Garner, brought the art of theme and variation to a level of sophistication that even Bach and his disciples would have appreciated. Finally, our line would lead over the harmonic horizon. In this land of vivid textures and muted shades, contemporary innovators test the capacity of traditional repertoire to absorb complex elaborations on basic chordal ideas.

With all three musical bases covered, where else can the jazz piano line go? There are two choices: It can wander into the wilderness of the avant-garde. Or it can feed back into itself, follow its own path back through the rhythm and melody and harmony, like a thread sewing the fabric of familiar ideas into fresh patterns. There is danger in choosing either option. But those with real talent can still prosper, no matter which direction they choose. Cecil Taylor, for one, continues to startle. And, among other players with a less experimental disposition, Andy LaVerne surprises us again and again.

In his Maybeck Hall recital, LaVerne displays a wide range of rhythmic and melodic expression. But, above all, he reaffirms his command of jazz harmony. Specifically, he follows the lead of Bill Evans in taking tunes we've heard a hundred times, examining each one's structure with respect to its chordal implications and coming up with voicings that we've never quite encountered before. – Robert L. Doerschuk

Steven Cerra [C] Copyright protected; all rights reserved

Although Carl Jefferson [the owner of Concord Records] is listed as the producer for all of the Maybeck Recital Hall solo piano recordings, and deservedly so, the series would not have materialized as it did without the loving devotion of Dick Whittington and his partner Marilyn Ross. Aside from Whittington being the originator of the project in the first place, both he and Ms. Ross assumed some producer-related functions throughout the seven years of its duration.

From the start, all three of these principals had to deal with many unusual demands and requirements as these 42 performances were both miniature concerts, as well as, recording sessions.

The combination of performing before only 60 or so invitees and the relatively small and intimate nature of the hall itself combined to create an almost recording-studio quality for each of these recitals. This combination also places some unusual demands on the solo Jazz pianist who on the one hand doesn’t have the ‘luxury’ of watching his miscues and failed experiments go up in vapor, nor conversely, the ability to have a recorded performance played back and re-done before a publicly acceptable version is decided upon by the artist.

So not only do we have 42 pianists performing in a largely unaccustomed or, at least, infrequent solo piano setting, which is challenging under the best of conditions, but each had to do it in front of a very small, discerning audience while being recorded with no chance to correct their mistakes with re-takes afterwards!

When Bill Weilbacher began producing his Master Jazz Recordings in 1967 [see Mosaic Records – The Complete Master Jazz Piano Series – MD4-140] he described the following as the ideal circumstances for the role of the producer.

“What was evident in the studio in every recording session is that playing the piano alone is hard work. When you play solo piano there is really no place to hide. There is a fundamental difference between recording and playing live before an audience. There is no necessity to be a persona in the recording studio, nor to entertain an audience. What is necessary is to do the job right. Because the job that must be done night will be played back for all to hear moments after the performance Is completed, and then, if released, heard by many others, the recording takes on an intensity and a seriousness that are different in kind from public performances. The recording becomes a permanent record of the performers work and, since these artists earn their living by playing piano, the recordings are extremely important to them.

No matter how we romanticize our jazz performers and their work, watching them in a recording studio gives a new and quite different view of how they earn their living.”

Unfortunately, in terms of the distinctions that Mr. Weilbacher draws between live performances and the recording studio, there’s was no such luck as far as the Maybeck Recital Hall project was concerned, both for the producers and for the performers.

Given the lack of these conditions for Carl Jefferson, Dick Whittington, and Marilyn Ross and the pianists who performed these solo recitals, it is a testimony to the creative and artistic talents and skills of all concerned how well these performances turned out.

The JazzProfiles editorial staff has been pleased to present this overview of this once-in-a-lifetime occurrence and hopes that the reader will seek out some, if not all of the previously reviewed 28 solo piano recordings in the series as well as the following 14 that conclude this review of the Maybeck Recital Hall solo piano series on Concord.

[For some additional insights into the piano in the Jazz tradition in general, and solo piano recitals at Maybeck in particular, see Gene Lees’ opening remarks in the insert notes to Don Friedman’s performance as contained under # 33 below].

Volume 29 – John Campbell [CCD-4581]

From the start, all three of these principals had to deal with many unusual demands and requirements as these 42 performances were both miniature concerts, as well as, recording sessions.

The combination of performing before only 60 or so invitees and the relatively small and intimate nature of the hall itself combined to create an almost recording-studio quality for each of these recitals. This combination also places some unusual demands on the solo Jazz pianist who on the one hand doesn’t have the ‘luxury’ of watching his miscues and failed experiments go up in vapor, nor conversely, the ability to have a recorded performance played back and re-done before a publicly acceptable version is decided upon by the artist.

So not only do we have 42 pianists performing in a largely unaccustomed or, at least, infrequent solo piano setting, which is challenging under the best of conditions, but each had to do it in front of a very small, discerning audience while being recorded with no chance to correct their mistakes with re-takes afterwards!

When Bill Weilbacher began producing his Master Jazz Recordings in 1967 [see Mosaic Records – The Complete Master Jazz Piano Series – MD4-140] he described the following as the ideal circumstances for the role of the producer.

“What was evident in the studio in every recording session is that playing the piano alone is hard work. When you play solo piano there is really no place to hide. There is a fundamental difference between recording and playing live before an audience. There is no necessity to be a persona in the recording studio, nor to entertain an audience. What is necessary is to do the job right. Because the job that must be done night will be played back for all to hear moments after the performance Is completed, and then, if released, heard by many others, the recording takes on an intensity and a seriousness that are different in kind from public performances. The recording becomes a permanent record of the performers work and, since these artists earn their living by playing piano, the recordings are extremely important to them.

No matter how we romanticize our jazz performers and their work, watching them in a recording studio gives a new and quite different view of how they earn their living.”

Unfortunately, in terms of the distinctions that Mr. Weilbacher draws between live performances and the recording studio, there’s was no such luck as far as the Maybeck Recital Hall project was concerned, both for the producers and for the performers.

Given the lack of these conditions for Carl Jefferson, Dick Whittington, and Marilyn Ross and the pianists who performed these solo recitals, it is a testimony to the creative and artistic talents and skills of all concerned how well these performances turned out.

The JazzProfiles editorial staff has been pleased to present this overview of this once-in-a-lifetime occurrence and hopes that the reader will seek out some, if not all of the previously reviewed 28 solo piano recordings in the series as well as the following 14 that conclude this review of the Maybeck Recital Hall solo piano series on Concord.

[For some additional insights into the piano in the Jazz tradition in general, and solo piano recitals at Maybeck in particular, see Gene Lees’ opening remarks in the insert notes to Don Friedman’s performance as contained under # 33 below].

Volume 29 – John Campbell [CCD-4581]

“A grand piano and a grand pianist in the most intimate setting: the combination of these elements has placed the Maybeck Recital Hall series among the most respected undertakings in modern jazz. But while the piano and the hall remain impressive constants, the pianist John Campbell may need some introduction.

Yes, he has appeared on albums by Clark Terry and Mel Torme and the Terry Gibbs-Buddy DeFranco band; and yes, he has even released two previous dates under his own name. But in the first 30 years of his life, John Campbell followed a path familiar enough to students of jazz history, perfecting his art in the quiet and undemanding surroundings of the Midwest - as a child and college boy in southern Illinois, and then as a local legend on Chicago's savvy jazz scene - before heading east for greater exposure and acclaim. As a result, even some of the more knowledgeable followers of jazz have yet to discover his galvanic approach to the jazz tradition.

For the best introduction to Campbell, though, turn to the music - in particular, his spectacular romp on the bebop warhorse Just Friends, which opens this album. Without fuss, he quickly introduces a surprising and invigorating touch by transposing keys midway through the first chorus, and then follows that pattern throughout the song, rocking between those two tonal centers. Clever, but not smug. Upon this skeleton he drapes an improvisation filled with delightful riffs and fragments that maintain their own structural integrity - such as the ascending triplet figure that first surfaces at the end of the fourth chorus, only to re-emerge as a full-fledged melodic device leading from the fifth to the sixth.

Many listeners resist that kind of micromanaged analysis of the music they enjoy. And with Campbell, you can easily just settle back while the music carries you on its journey, happy to close your eyes and absorb the picaresque sweep of his soloing. But you do so at the risk of missing so many remarkable details. The surprising twist in a smoothly skimming melodic line, for instance. Those lightning transpositions of key. The brilliantly inserted sequence. The sudden explosion of doubled time, as if the improvised passage had built up enough tension to override the safety valve of musical meter.

Despite his other musical gifts, John Campbell is first and foremost a melodist, his music dominated by the eastern half of the piano keyboard. …” Neil Tesser

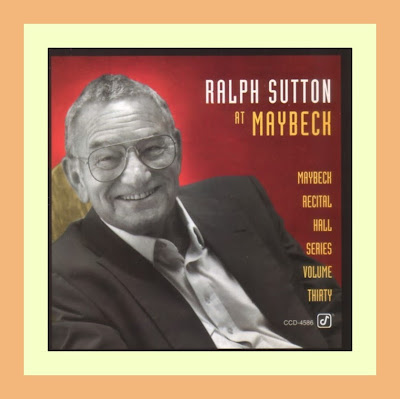

Volume 30 – Ralph Sutton [CCD-4586]

“….Fats Waller was an early idol, though Ralph says regretfully "I never saw him in person, but of course I was aware of his career on records." (Waller died when Ralph was 11.) Honeysuckle Rose includes the verse and eventually moves into stride. Although Ralph has a reputation built largely on his proficiency in ragtime and stride, he is in fact an all-around pianist whose expertise extends to the classics.

His range becomes evident as he moves from Fats Waller to Bix Beiderbecke, whose In A Mist he has interpreted for years with flawless fidelity. "I was working with Teagarden when Jack sent me over to Robbins Music to pick up a Bix folio. That was the first I knew of his compositions. I still have that folio."

Ralph returns to Waller with Clothes Line Ballet, a delightful work which Fats recorded in 1934. "I first heard Fats when I was nine. I bought a folio of his tunes too."

In The Dark is one of the piano pieces written but never recorded by Beiderbecke. It has the same haunting quality and harmonic subtlety that marked all of Rix's works, which were decades ahead of their time.

Fats Waller's Ain't Misbehavin' is a melodic Waller marvel that made its debut in the revue "Connie's Hot Chocolates" in 1929. Again Ralph includes the verse, with its unpredictable harmonic line.

Echo of Spring is the most attractive of the many works left us by Willie "The Lion" Smith. Both Ralph and I recall sitting beside the Lion as he played this elegant work and following its beautiful melodic contours. That rolling left hand is an essential part of its charm, which of course Ralph retains.

Dinah, a pop hit of the 1920s, has touches of the Lion in Ralph's performance. Love Lies is probably the most obscure song in this set; Ralph learned about it during his Teagarden days. It was written by one W. Dean Rogers in 1923.

Russian Lullaby is simply a song Ralph heard around. "I never saw the music on this one. Who wrote it? Irving Berlin? No kidding - I didn't know that."

St. Louis Blues was the most famous of the W.C. Handy blues series.. Written in 1914, it starts as a regular 12 bar blues before moving into a 16 bar minor strain. Sutton starts with a series of dramatic tremolos, then takes it at an easy lope.

Viper's Drag finds Ralph again retaining the spirit of Fats Waller in a 1934 tune, the title of which was an early term for a pot smoker. It's one of Fats's relatively few numbers in a minor key.

Finally there is After You've Gone, which goes all the way back to 1918 and was originally played, as I recall, in the slow tempo with which Ralph introduces it, as a 20 bar chorus. Later he shifts gears into the now more generally accepted long-meter, 40 bar treatment.” – Leonard Feather

Volume 31 – Fred Hersch [CCD-4596]

"Describing music -any music -is largely a bureaucratic function. It involves categories and qualifications, not to mention paperwork. This is especially true of jazz, for which tradition lends heft to files marked "swing" and "bebop."

A higher ideal, and a truer litmus test, is improvisation. At best, the musical improviser frees us from our baggage, so we are free to explore new worlds. Pianist Fred Hersch has always recognized this truth, and that recognition combined with virtuosity and technical skills - has been a liberating force fueling the development of his sound.

"When I'm playing music that I connect with," Hersch says, "the form and the changes don't limit me, they inspire me to say something original and personal." These statements have taken shape in a wide variety of settings (from jazz trio to classical orchestra) and across a broad sweep of musical territory (from Cole Porter to Scriabin to Monk, for instance). "When I play in a group, I choose musicians who will surprise me."

When the opportunity to record this live solo album arose, Hersch knew he'd need to surprise himself. Before sitting down at the grand piano beneath the wood and leaded glass of Maybeck Hall, he announced to the audience that "half of the tunes I'll play are songs I know intimately, the other half are songs I don't know that well." With that, Fred Hersch took his place alongside the thirty distinguished pianists already documented in this series. …. This was his first solo recording." – Larry Blumenfield

Volume 32 – Sir Roland Hanna [CCD-4604]

"Volume Thirty-Two of Berkeley's Maybeck Recital Hall series - Concord's exalted project of recording under optimum conditions those "Poets of the Piano" mostly confined to minor labels - is the summing up of Sir Roland Hanna's career that spans nearly four decades.

This album is Sir Roland's life: the sanctified church, rhythm n' blues, classic piano literature, the grand Romantic tradition of the 19th Century, French impressionism, ragtime, Harlem stride, Tatum, bebop, Garner, the Blues, funk, avant-garde, and the explosion of song-writing genius that blessed America in the Twenties and Thirties. More than half the Maybeck recital affirms Sir Roland's love affair with George Gershwin.

What is most immediate in this recital is Sir Roland's uncanny sense of structure, his flair for drama and for breathtaking climax. Each number unfolds as a completely realized composition. A consummate mastery of the keyboard permits his fertile imagination and puckish wit to run riot. – Grover Sales

Volume 33 – Don Friedman [CCD-4608]

"The keyboards are unique in the family of instruments. Keyboard instruments can function alone. So can the guitar, but in a more limited way, and keyboards, including harpsichord and organ and, later, the piano, have dominated Western music since before baroque times. Since Mozart's time, the piano has been the king of these instruments. All other instruments have an essentially ensemble character: they need friends around them to fill out the harmony. Piano doesn't.

If you listen to early jazz records, you will find that when it came to allowing the pianist a solo - Earl Hines, for example - no one knew how to go about it. So everybody stops playing while the pianist does his thing.

Eventually the piano was absorbed into the jazz ensemble by limiting the way the pianist played. But pianists can do much more than they are usually called upon to do in jazz. Secretly, Oscar Peterson has suggested, they dream of going out there and doing it alone instead of comping chords for horn players.

In 1989, JoAnne Brackeen was about to do a solo performance at Maybeck Hall, a small and exquisite location in Berkeley, California, with an excellent piano. She called Carl Jefferson to ask that he record it. Fortunately for the world, he did, and the resulting album became the first of a remarkable series of Maybeck Hall recordings.

The series has become a singular documentation of the state of jazz piano in our time. Carl has not-so-slowly been documenting in sound the astonishingly rich state of jazz piano as our century nears its end. He has let this brilliant body of pianists go into a sympathetic hall and show just what it is they can do when they play solo.

It is helpful to picture the room. It is not large; indeed it seats only about 50 persons. Those in the front row are very close to the player; there is no sense of distance between the performer and the audience. The room is beautifully wood-paneled and its acoustic properties are outstanding.

Don Friedman's is the 33rd in this series of Maybeck Hall recordings, and he reacted like everyone else before him.

"I loved the room and I loved the piano," he said. "And the audience was wonderful. I couldn't have been more comfortable."

Then, too, for Don it was a bit of a homecoming. Though he lives in New York City, he is a Bay Area boy, having been born in San Francisco in 1935.

The term "under-appreciated" gets worn with time, but there are few musicians it fits more accurately than Don. He has worked with an amazingly disparate group of jazz players, from Dexter Gordon to Buddy DeFranco, from Shorty Rogers to Ornette Coleman. He worked with Pepper Adams, Booker Little, Jimmy Giuffre, Attila Zoller, Chuck Wayne, and Clark Terry. That is flexibility, not to mention versatility. Yet this is not widely appreciated. …

If Don is indeed, as many musicians think, under-recognized, this latest album in the distinguished Maybeck Hall series should help correct this." - Gene Lees

Volume 34 – Kenny Werner [CCD-4622]

"I try to be prepared for whatever comes through me," Werner explained. "The purpose of the concert is to get to what I call an ecstatic space. Hindus call it shakti, and Bill Evans called it the universal mind."