© - Steven A. Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“Possessed of both his own conception, which made Mobley's music readily identifiable, and the equally rare inspiration that also made listening to his work eminently satisfying, Mobley was perpetually eclipsed throughout his career by more extroverted and influential stylists. ...It has only been in the years since he stopped recording (...), and especially since his death in 1986, that the exceptional quality of his playing and writing has begun to receive a commensurate measure of respect.”

- Bob Blumenthal, Jazz author, columnist and critic

"The most lyrical saxophonist I've ever heard. He sang into his horn."

- Benny Golson, tenor saxophonist and composer

At this point, my ongoing Mobley Quest moves away from features that focus on one of Hank’s many recordings as a leader for Blue Note [There were 24 in all.] and reverts back to the larger studies on Hank, all of which have been posted on the blog to date including Simon Spillett pieces -”Hank Mobley’s recordings with Miles Davis - UPDATED” and “Looking East: Hank Mobley in Europe 1968-1970,” the John Litweiler interview that appeared in Downbeat in 1973, Derek Ansell’s book Workout: The Music of Hank Mobley which was published by Northway in 2008 and the two Jazz Monthly essays by Michael James from 1961 and 1962, respectively.

The only extensive writing on Hank’s career which has not been presented so far in my MobleyQuest are the following booklet notes by Bob Blumenthal’s to the Mosaic Records box set of Hank’s 1950s Blue Note recordings.

An especially beneficial aspect of Bob’s Mobley essay is that it contains many references to MY GROOVE, YOUR MOVE, a limited-edition program compiled by Kimberly Ewing and Don Sickler for a concert of Hank Mobley's music presented in Carnegie Hall's Weill Recital Hall on October 29, 1990.

I’ve said this before but it bears repeating: during the many years that he wrote about Jazz for The Boston Globe, CD Review, The Atlantic Monthly, Downbeat and numerous other publications, Grammy-Award winning author, columnist and critic Bob Blumenthal became one of my most consistent teachers about all-things-Jazz

For his long affiliation with it and studied application of it, Bob knows the music.

Equally important is his ability to communicate this knowledge and awareness in a writing style that is clear, cogent and concise.

Bob’s a mensch and a mentor and it’s always a privilege and a pleasure to represent his work on these pages.

© - Bob Blumenthal: copyright protected; all rights reserved; used with the author’s permission. [Paragraphing modified in places.]

“On the back cover of MY GROOVE, YOUR MOVE, a limited-edition program compiled by Kimberly Ewing and Don Sickler for a concert of Hank Mobley's music presented in Carnegie Hall's Weill Recital Hall on October 29, 1990, the baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter is quoted about Mobley's aspirations. Most of the tenor saxophonist’s wishes have to do with the conditions performing jazz musicians seek yet find all too rarely — clubs with dressing rooms, good pianos and accommodating acoustics — but Mobley also was looking for an upgrade in listening attitudes. "Somewhere to play where people aren't just comparing you to someone else!" was the way Nica put it.

Few musicians had greater cause to seek such a forum for their playing than Hank Mobley, who could serve as Exhibit A when building a case against the poll-driven, King of the Hill approach to jazz appreciation. Possessed of both his own conception, which made Mobley's music readily identifiable, and the equally rare inspiration that also made listening to his work eminently satisfying, Mobley was perpetually eclipsed throughout his career by more extroverted and influential stylists. Throughout the period represented by the present collection, his work was often downgraded as a lesser version of Sonny Rollins; and in 1960 and '61, when he worked with Miles Davis and recorded what are his greatest sessions under his own name, he was dismissed for not measuring up to his predecessor in the Davis band, John Coltrane. When the avant-garde innovators dominated the attention of jazz critics a few years later, Mobley's playing was often dismissed as old hat and irrelevant. It has only been in the years since he stopped recording (his last session, co-led with Cedar Walton, took place in 1972), and especially since his death in 1986, that the exceptional quality of his playing and writing has begun to receive a commensurate measure of respect.

Mobley may have been doubly cursed. He was a great tenor saxophonist in an era that enjoyed an abundance of great tenor saxophonists, and his particular skills were not as attention-grabbing as those of several peers. Consider his friend John Coltrane, who recorded with Mobley on three occasions during the period covered by the present collection. Even at this stage of his career, when Coltrane's ideas were often partly formed and imperfectly executed, his fervor is often more immediately arresting than Mobley's more subtle approach to harmony and rhythm. Mobley's penchant for doing things his own way only reinforced the difference.

In the invaluable interview/article "The Integrity of the Artist — The Soul of the Man" that Down Beat published in 1973, Mobley told John Litweiler: "When I was about 18, [my uncle] Dave told me ‘if you're with somebody who plays loud, you play soft, if somebody plays fast, you play slow. If you try to play the same thing they're playing you're in trouble.' Contrast. If you play next to Johnny Griffin or Coltrane, that's hard work. You have to out-psych them. They'd say, 'Let's play CHEROKEE,' I'd go, 'Naw naw — ah, how about a little BYE BYE BLACKBIRD?' I put my heavy form on them, then I can double up and do everything I want to do."

This philosophy plus his talent should have won Mobley more respect in the 1950s; but, then again, it was a golden era for tenor players. Mobley recorded with several of the best — Coltrane and Griffin on the latter's Blue Note album A BLOWING SESSION and Zoot Sims and Al Cohn plus Coltrane on Prestige's TENOR CONCLAVE — not to mention perennial poll winner Stan Getz, the two Sonnys (Rollins and Stitt), Lucky Thompson and still-inspired patriarchs of the horn like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and Ben Webster.

Mobley found his own voice amidst these giants, notwithstanding the discernible influence of Rollins in the '50s and Coltrane a decade later. He had a sound on the horn which he himself identified as "round," a gorgeous, centered tone filled with soul and tenderness. "The most lyrical saxophonist I've ever heard," Benny Golson said. "He sang into his horn." Mobley's musical knowledge was highly refined, and emerged with particular clarity in his sophisticated harmonic approach. Horace Silver recalled that "He'd write some different, alternate changes, and they'd always be so inventive and so creative, so beautiful. A very musical mind, a harmonic mind."

As far as his rhythmic concept went, Al Grey captured the impact of Mobley's playing as well as his writing when he noted that "All of [Mobley's] tunes flow so freely, you can really swing with them — I mean really swing!" In addition, Mobley possessed organizational skills unusual in a musician who spent so much of his career as a sideman. He had a special knack for writing material for the blowing sessions of the period, often coming up with compositions in the studio on the spur of the moment. These pieces, frequently containing harmonic wrinkles that set them apart from mere rewrites of standards, were designed with the specific players on the date in mind, to the point that in conversations with Don Sickler, Mobley recalled melodies that Sickler would hum by naming musicians who had played on the original recordings.

He was also a master ensemble player, particularly skilled in blending with talented trumpet partners. This made him highly attractive to the independent jazz labels in the mid-50s, when both the new hard-bop style and the advent of the 12" long-playing album generated a recording boom; and it ultimately won Mobley the role, particularly during 1957, of de facto house tenor for Blue Note Records.

Recalling the busy days in Rudy Van Gelder's original Hackensack, New Jersey studio, Mobley told Litweiler that "Savoy recorded on Fridays, Prestige on Saturdays, Blue Note on Sundays, something like that. They'd buy the whiskey and brandy Saturday night and the food on Sunday — they'd set out salami, liverwurst, bologna, rye bread, the whole bit. Only Blue Note did it; the others were a little stiff. If we had a date Sunday, I'd rehearse the band Tuesday and Thursday in a New York studio.... We'd be making a tape, and sometimes my horn might squeak, and Frank Wolff would say, 'Hank Mobley! You squeaked! You squeaked!' — and the whole band would crack up, we couldn't get back to the tune. And old Alfred Lion would be walking around, (snap) 'Mmm!' (snap) — 'Ooh!' (snap) — 'Now vait a minute, it don't sving, it don't sving!' So we'd stop and laugh, then come back and slow it down just a bit. Then he'd say, (snap) (snap) — 'Fine, fine, dot really svings, ja!'"

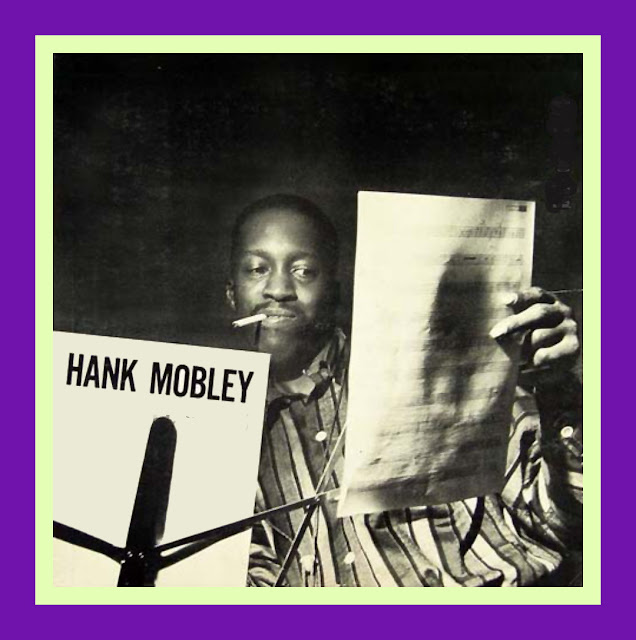

Mobley's relationship with Lion, Wolff and Blue Note, which began shortly before the first music included here was recorded and continued through 1970, was as important to the saxophonist's career and his legacy as any hook-up with a fellow musician. During its active life, most people took the pairing of artist and label for granted. Today, when both the sound and the look of Blue Note albums has taken on iconic status, Mobley's music and his visage are at the center of the legend. He graces the cover of The Blue Note Years: The Jazz Photography of Francis Wolff (Rizzoli, 1995), and 13 additional images inside make him the dominant presence in the book.

Mobley loomed large in the recording studio as well, particularly in the incredible 15-month span of 1956-8 that dominates this collection. At the dawn of the 12" era, Lion and Wolff found (albeit in a more harmonically complex and less romantic concept) the focal point for a series of studio jam sessions that Prestige was employing so successfully with Gene Ammons.

Unfortunately, another factor led to the extensive documentation of players like Ammons and Mobley at the time. "I had the knowledge," Mobley confessed to Litweiler in 1973 regarding the heroin habit that frequently interrupted his career. "When I got strung out it was my own fault. A person getting strung out at age 18, that's a problem. He doesn't even have a chance to learn what life is about. By the time I got strung out, I had learned my instrument, I was making money." For great players like Ammons and Mobley, drug addiction left them more inclined than they otherwise might have been to record frequently, and the wealth of material generated allowed jazz labels to sustain the public presence of these musicians when problems physical and legal made them otherwise unavailable. It is tempting (yet hardly fair in the case of such respected producers from the period as Lion, Orrin Keepnews and Lester Koenig) to view this situation as one of record company exploitation; at the same time, the realities that faced musicians like Mohley in the 1950s must be kept in mind lest we ascribe periods of particular inspiration or lack thereof to when albums were recorded. In the present case, Mobley became a key player in the Blue Note orbit at a point when his particular skills and the emerging format for studio jazz recording were in a most complimentary zone.

This yielded music that has been doggedly sought out by many jazz fans and has eluded too many more through limited availability. Of the nine albums represented herein, two were never released and four others were never reissued domestically. Those fortunate enough to have tracked down all nine of the original albums (including the two that first appeared in Japan) will find nine alternate takes included (and programmed after the originally issued material, which makes for better casual listening and will not impede any comparison-minded student of the music willing to employ a CD player's program function). This is not all of the music Mobley made during his first recording phase and — given his talent, consistency and ubiquitous presence in so many important bands and on so many labels — it is not all of the best Mobley from the '50s. What we have here is a magnificent overview of the period, with some of the most memorable players of the day giving themselves to the indelible concepts of a musician who is finally getting his due as a magnificent tenor saxophonist and composer.

Hank Mobley was born on July 7, 1930 in Eastman, Georgia, and raised in Elizabeth, New Jersey. There was much music in his family, particularly piano music. The aforementioned uncle, Dave Mobley, played piano among other instruments, and his mother and grandmother also played keyboards (his grandmother was a church organist). Piano became Mobley's first instrument; then he picked up the tenor sax at age 16 and basically taught himself the horn. On his uncle's advice, he listened initially to Lester Young and then to Don Byas, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt. "Anyone who can swing and get a message across," as Mobley explained his influences to Leonard Feather in 1956.

By his late teens, Mobley was working as a professional musician. He was hired by Paul Gayten and worked the rhythm and blues circuit with him between 1949 and '51, having been recommended by Clifford Brown (who had not heard Mobley play at the time but was aware of his growing reputation). "Hank was beautiful, he played alto, tenor and baritone and did a lot of the writing," Gayten recalled. "He took care of business and I could leave things up to him." The Gayten band also included baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne and future Ellingtonians Clark Terry, Aaron Bell and Sam Woodyard. Working with the last three no doubt eased the way for Mobley's two-week stint as Jimmy Hamilton's replacement in the Ellington Orchestra during 1953. ("I didn't play clarinet, but I played some of the clarinet parts on tenor," he later recalled). While the band recorded, the material did not feature Mobley as a soloist.

Mobley's jazz recording debut was the product of a job he held in the house band of a Newark nightclub after leaving Gayten in 1951. Another promising youngster and future Blue Note artist, pianist Walter Davis, Jr., was also a part of the group, and the opportunity to back visiting stars including Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Billie Holiday, Bud Powell and Lester Young was invaluable to their rapid development. Max Roach hired both Mobley and Davis after appearing at the Newark club, and brought them into rooms like the Apollo Bar before recording with them for Debut in March 1953. The session (now available on OJC) included both quartet and septet tracks and captures an already recognizable tenor stylist and composer. There were three melodically appealing Mobley originals, including the striking minor-key KISMET, while his imaginative chordal substitutions and fluent shifting of accents also enlivened the standard GLOW WORM and the Charlie Parker blues CHI CHI. Roach reportedly tried to summon both Mobley and Clifford Brown to California to form what would become the Brown/Roach quintet in the summer of 1953, but was only able to locate the trumpeter.

Back on the East Coast, Mohley gained further experience with Davis, Tadd Dameron, Milt Jackson and J.J. Johnson. For much of 1954 he worked with Dizzy Gillespie, and participated in four of the trumpeter's recording sessions. While among the lesser-known items in Gillespie's extensive discography, these tracks show Mobley to good advantage in a rare big-hand setting on Chico O'Farrill’s MANTECA SUITE (where Mobley plays the half-chorus solo on the THEME movement covered by Big Nick Nicholas on the original 1947 recording) and as a clearly formed stylist on the sextet titles RAILS and DEVIL AND THE FISH.

After leaving Gillespie in September 1954, Mobley joined pianist Horace Silver's quartet at Minton's Playhouse, a group completed by bassist Doug Watkins and drummer Arthur Edgehill. "On weekends Art Blakey and Kenny Dorham would come in to jam, 'cause they were right around the corner," Mobley recalled to Litweiler, which led to Silver's first quintet session for Blue Note with Dorham, Mobley, Watkins and Blakey in November 1954. The compositions were all Silver's; but the entire quintet was dazzling, with Mobley's solo catapulting off band breaks on ROOM 608, preaching at medium-slow tempo on CREEPIN' IN, flying against the seesaw momentum of STOP TIME and laying bare the saxophonist's soulful blues conception on DOOLIN’. The session was issued as Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers, working a variation on the Messengers name that Blakey had employed for a larger ensemble several years earlier; and the five musicians decided to work in a cooperative relationship whenever any one of them was offered work.

It did not take long for the Messengers's blues-and percussion-driven new strain of modern jazz to take hold, or for Mobley to establish himself as one of the music's primary new voices through additional appearances on Blue Note. He recorded in a Dorham sextet that also included Silver and Blakey in January 1955, and with Silver and the Messengers again in February on a session that included the funky hit THE PREACHER (where the audacious entry of the tenor sax is a highlight) and Mobley's own typically "heavy form" HANKERIIN'. In March, Mobley and Blakey participated in Julius Watkins's sextet session, nine days before Blue Note gave the tenor saxophonist his own first opportunity to appear on vinyl as a leader.

(A) MARCH 27, 1955

Mobley considered his debut session - The Hank Mobley Quartet [BLP 5066] to be his best early recording and indicated that significant preparation had preceded the actual visit to Van Gelder's studio. The date features his tenor sax with the Messengers rhythm section, and has been particularly hard to find since its 1955 release as Blue Note 10" LP 5066. United Artists reissued the session in a rare facsimile edition 20 years later and it was sold only in Japan and Europe. Otherwise, it has been available as one side of a Japanese 12" LP (sharing a disc with George Wallington's Blue Note session) and on a Japanese compact disc where the two alternate takes first appeared.

At this point in the insert booklet annotations, Bob launches into a detailed, track-by-track descriptions of the nine LPs [and three CD reissues] that form the Mosaic Complete Blue Note Hank Mobley Fifties Sessions [MD6-181] and concludes with this statement:

“When it came to music, Hank Mobley was extremely sure-footed in this period. If his drug problem created a less than steady personal life and slowed his recording activities significantly for much of 1958 and 1959, he was able to bounce back with Blue Note, when he entered a truly golden age on albums like Soul Station, Roll Call and Workout.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments here. Thank you.