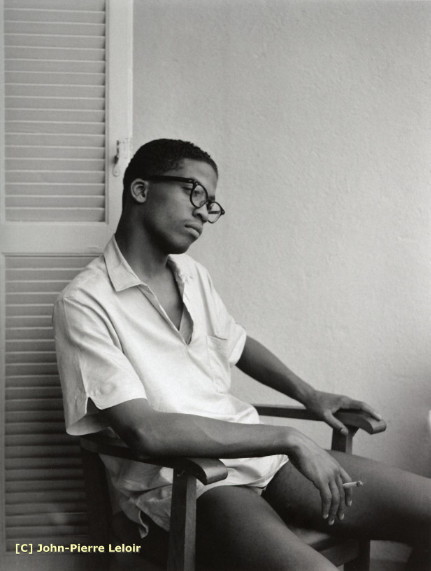

It’s hard to believe that this interview was published half-a-century ago in the Jan. 21, 1971 edition of Downbeat.

Herbie was just finishing his first decade on the Jazz scene.

But then, as now, Herbie’s ability to articulate what’s happening in the Jazz World in general and in his music in particular is straightforward and full of insights.

“Herbie Hancock had been doing SRO business all week at the Cellar Door in Washington, D.C., and it seemed inconceivable that things could get any better. The crowds were receptive and the group—consisting of Eddie Henderson, trumpet, fluegelhorn; Julian Priester, trombone; Benny Maupin, tenor sax, flute; Hancock, keyboards; Buster Williams, bass; Billy Hart, drums— really swung. It was Saturday night and the Cellar Door was as jammed as I had ever seen it, but there were two people present in the audience who probably helped to inspire the group to even greater heights than usual: Dizzy Gillespie, seated in a chair on the aisle, and Bill Cosby, seated on the front stairs. It was just that crowded.

As expected, the group really let it all hang out on "Fat Albert Rotunda." There are magic moments in a jazz listener's life when a certain combination of factors produces a truly memorable experience. It was after this performance, the last set of an exceptionally fine week, that I interviewed Herbie Hancock. I had been particularly impressed with the way in which the rhythm section seemed to work, and the thought struck me that they played so well together and got so much out of three pieces that there did not appear to be that much need for anything else. I was curious why Herbie wanted the sextet sound and feeling; thus my first question to him and the start of a rather revealing interview.

Brooks Johnson: One of the first questions that comes to mind, particularly when I heard the trio work, and the way it was swinging, is what are your basic motivations for performing with a group consisting of six pieces?

Herbie Hancock: Well, when I did the sextet album, I liked the sound of that particular combination of instruments. So right then and there, I decided that if I got a group together, it would have to be that. In using this instrumentation, I've got the same flexibility a small group has and yet I have a vehicle for getting orchestral colors the way a large group might. I've got three horns—that's almost like a lower limit for making what we call harmony. You can do it with two instruments, but three is the least comfortable number of instruments for getting harmonic colors. Let me explain that just a little bit: The three instruments being trombone, fluegelhorn and alto flute for the ensemble, I can use, I get a chance to experiment with woodwind color, which a saxophone will not give you. And then the fluegelhorn has enough of a trumpet quality, yet enough of a more blending quality because of its mellowness so I can use it with the alto flute. It sort of overlaps in sound, and then the trombone gives it a little brassiness. This way, I get a chance to really use different kinds of colors, not just because of the harmony I can use, but because of the instruments that I have.

B.J.: Now, assuming that you had a concept in mind, or a type of sound you wanted, I'd like to know when you started to choose your personnel, and let's review them individually, by what criteria; what were you looking for, what did you hear? Let's start with Billy Hart—what attracted you to him?

H.H.: Well, actually, I'd heard him with Wes Montgomery and Jimmy Smith. That alone didn't convince me that he would be the right drummer for my band. It was just that I had to have a substitute drummer one day, and Buster Williams told me to call Billy Hart—he said he's out of sight. I said OK. I really didn't know he was going to work out.

When he swings, when we're doing a thing that's supposed to swing, he swings hard. And when we're doing things that are... well, I guess I can break it down by saying the scope of the band is very broad. We do things from finger popping, swinging things through things that are more like rock or rhythm and blues, on through impressionistic-type things, and then on up to very far out things. So we cover a very wide area, and I want to have somebody who can do all of that—just play music for the sound of the music, not a guy that can play a bossa nova, and he can play a rock beat, and he can play this or that, not that, but a guy who has a style that encompasses everything. Now that applies to all the guys in my band.

B.J.: What particular quality do you hear and feel most from Buster Williams?

H.H.: His walking style. When he walks on the bass, he places the note - in exactly the right place in the beat so that he really swings. His musical conception is what really knocks me out.

B.J.: How about Julian Priester—he's a recent addition to the group, right?

H.H.: Right. Julian is probably more steeped in tradition, I think, than the other guys in the group. He worked with Max Roach quite a few years ago, and with Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington. But he knows the trombone. He just brought up, a couple of days ago, his bass trombone, and he's going to bring an alto trombone in addition to a tenor trombone, so he's going to play all of those on the gig. It was funny, the first few days he worked with us, I didn't know whether he was going to give me what I needed.

B.J.: And Eddie Henderson?

H.H.: Well, there's a certain lyrical quality about Eddie's playing that is the kind of thing I was looking for. He doesn't just play the changes and run chords off the changes. He constructs melodies that stand alone without the changes, and builds them a lot on composition.

B.J.: We talked earlier about the particular use of the fluegelhorn. Do you want to elaborate on that and how it brings in the certain tone quality and texture that you're looking for?

H.H.: The fluegelhorn has a sound that to me is somewhat between a trumpet and possibly a French horn. It's sort of a mellow trumpet because of the construction of the horn itself. It blends better with the alto flute and the trombone — better than the trumpet does. We use the trumpet when we need a lot of pure power. But on the other things, we use the fluegelhorn because it blends better with the other instruments.

B.J.: The saxophone player is Benny Maupin. What is it that particularly recommends him, or his playing, to you?

H.H.: Well, Benny plays pure sound. He gets inside of the music that's going around and grabs out the core. You know, he uses the chord changes only as a point of reference in most cases, and I mean a point. You hit that point and he goes off someplace else and comes back and hits that point and goes off someplace else. In addition to that, his style—all the guys' styles broaden the scope of the band.

B.J.: OK, now you have five talented musicians and yourself, which makes six. Now you've had it both ways — as a side-man, part of a rhythm section, you had a studio thing, and now you have your own group. Can you point out the things that you dig that are special and peculiar about having a group?

H.H.: I get a chance to play my music and, as a group, we get a chance to evolve the music. You can't do that at a recording session that is a one-time thing — you have to play tunes over and over in different settings on different occasions. Subsequently, the tune will change shape depending on the individual feelings of the musicians who are playing it.

B.J.: What are some of the problems about being a leader?

H.H.: Well, I'm responsible for paying the guys and making sure that they work so l can keep a hand. That's one rough thing, because I have to worry not only about my family, I have to worry about six families— I have to be aware they're there, and if I'm going to keep a band, I have to make sure that we're working so that they can feed their families as well as I feed mine. Secondly, I guess the leader, depending on the I guys in the group, can run into problems with personality, and I guess it's up to the leader to really keep the situation open enough so that personality conflicts don't erupt, keep some kind of harmony in the band. It's kind of rough.

Also — well, this isn't much of a problem with this band — a bandleader could run into the problem of not allowing enough of the personality of the individual players to be present in the music. They have to all feel that they are responsible for doing the best they can. If they don't feel the responsibility, if they don't feel that they're really contributing, then they may feel that they're sort of dead weight in the band—just holding an instrument and not serving a real function. So their personality has to be present in the music.

B.J.: What about the experience or the influence that your stay with Miles Davis might have had? For example, what things about Miles, as a sort of group leader, do you yourself think were worthwhile salvaging in terms of bringing together your own group?

H.H.: One thing I just mentioned — the openness of the music. With Miles' band we were all allowed to play what we wanted to play and shaped the music according to the group effort and not the dictates of Miles, because he really never dictated what he wanted. I try to do the same thing with my group. I think it serves this function that I just mentioned-—that everybody feels that they're part of the product, you know, and not just contributing something to somebody else's music. They may be my tunes, but the music belongs to the guys in the band. They make the music — it's not just my thing — that's one thing.

Miles showed me some other things, even the construction of the music. I used to bring tunes to Miles and he would take things out and put different bass notes on certain chords and extend certain phrases, and put spaces in there that I hadn't even conceived of. It's kind of hard for me to describe exactly what he does, but he uses certain devices in order to make the tune more meaningful and make it — actually, make it slicker. Miles really knows how to make a tune slick, and I learned a lot about that from watching how he goes about making a tune. He doesn't put too much in it or too little, you know, and none of his stuff is commonplace.

B.J.: There seems to be a trend in music, probably exemplified by your band, toward playing music that a lot of people can relate to. It's not so far removed that the listener can't get into it. Would you care to address some remarks to that — what do you think the trend is and the feeling is in terms of, say, just as a music, and in terms of the audience returning to the clubs?

H.H.: Well, let's start with my group. I personally have always been involved with a variety of music from things that I did with Miles to the things I did with Wes Montgomery to the things that Mongo Santamaria got involved with, and so I've had a chance to experience firsthand a broad scope of things. One thing I wanted the group to be involved with is the whole, total picture of music. I think everybody in the group enjoys that as well as I do. This keeps the group interesting to its members and keeps the music interesting to the audience. Now that's just part of the picture.

Another part is that when we play, we're not playing for ourselves, purely. We are conscious of the fact that there are people out there. It has nothing to do with the people who are paying to hear us or whatever it is. It's just the fact that the people are there and they are part of the surroundings that produce the music. We're just a vehicle that the music comes through, so the audience plays a definite part — we don't try to shut them out of the musical situation.

B.J.: They're part of the whole catalytic process then, and the creation on any given night to some degree reflects whatever is coming from the audience itself?

H.H.: Right. To get into the other more general question you were asking about the direction of jazz today. There was a time when you could say that there was a direction in jazz, and the people who didn't follow that direction usually stood alone, you know. But there was a general direction that everybody went in. Not so much today. I think there are many directions happening in jazz, and you can't pin it down to one. There is what's called the avant-garde; there's what's called the jazz-rock idiom; there's what's called I guess you'd have to say a post-bebop flavor to music. Then there are some groups that are involved with total theater — involving not just music but some visual things too. Right now, I'm thinking of the AACM in Chicago, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, and it's really hard to pin it down.

There are certain people like, for example, Miles Davis, Tony Williams, Cannonball Adderley and myself who have gotten into using electronic instruments— you know, electric bass, electric piano and exciting instruments like the bass clarinet in my band, and in Miles' band, he's got Airto Moreira. he's a Brazilian, playing all kinds of Brazilian instruments. And in Cannonball's band, he's got the electric bass and sometimes they even play guitar. The bass player, Walter Booker, plays guitar sometimes, and Joe Zawinul plays the electric piano.

But these groups are influenced by things that are happening in rock, and we've found ways to use some of the things we've heard in more commercial aspects of black music that can be employed to expand our horizons. But that's not the only direction that the groups that I've mentioned are going in. Miles is still as far out as he's ever been—farther out, if anything. The same thing with my band, and Cannonball's too. In addition to that, there are also the more lyrical-type things that we also do that may be linked with impressionistic flavor, if anything.

B.J.: My feeling is that the thrust or partial thrust of some of the music is going to bring a lot of the people back in—people like myself, who are used to hearing changes and things like that. Do you think this is going to continue to be the case?

H.H.: Well, we don't play changes the way we used to anymore. But we are, in most cases, aware of the changes. In most cases, we're not just playing a melody and then just going off and playing whatever we feel at the moment. There usually is a chordal basis that underlies whatever direction that we go in.

B J.: There is a common denominator that has some substance and some form that runs through all music, and I think the audience eventually picks it up. There's got to be a certain common denominator of familiarity. But too often the avant-garde went beyond the range of familiarity for listeners and even in some instances, musicians as well.

H.H.: Could be. On the other hand, I think that since our involvement in the avant-garde, the music in that particular direction is really beginning to take shape. It's not amorphous anymore, I mean, the sound is not totally unfamiliar to the musician anymore, so that certain things have been established, even in the avant-garde. There are certain things that are part of it. One thing seems to me to be the energy that comes out of the rhythm section. You take a guy like McCoy Tyner, and Elvin Jones or Freddie Waits or whoever he uses on drums. Even though they may start out with a song, and after the song is played, they leave the changes and just play what you might call a through-composed piece — it just goes straight ahead — the energy level sustains the interest of the audience. There are ways of using dynamics in playing your melodies no matter how jagged or how weird they'll be that can stimulate some inner feelings within yourself as a listener that, even though you may not he able to relate to the notes or the chords or the sounds that are being played in a way that you're used to relating to them, you still react because that emotional element is there. It can be quite a shock to walk into a club and hear some music that you’ve never heard before, but you are totally stimulated by.

B.J.: So the person should listen for and feel for, not the familiarity of the changes, but look to the energy, the dynamics as a source of familiarity as opposed to looking for the progressions and things like that?

H.H.: Actually, the person shouldn't listen for anything. The person should just go in there and listen to whatever is going on and then make his decision. He should try not to walk in with criteria in his arms, but just walk in empty-handed and listen to whatever's going on. If it feels good, he digs it —doesn't deny it — but if it doesn't feel good, familiar or unfamiliar, nobody should object if he is not able to accept it. But so much of what's happening today in the most modern aspects of jazz does feel good — I think even more so than in the past.

B. J.: Let me ask you this, then, in some note of closure. What — either primary or secondary, defined or undefined — goals or objectives do you envision for your group? What is it you want to accomplish?

H.H.: Well, I'd like to bring more people into listening to my music, so that whatever direction we might take in the future, they might have an easier time following that direction. I think that the material we're using now should help that situation. In other words, part of what I want lo do is find that part of my musical being that relates to the most people because I'm a "people,” too, you know, so part of me is part of them, and there must be some part of me that they understand just as there is a part of them that understands. You know, we're all really the same, and I'm searching for that part of my musical experience that relates to them. If they can grasp that, then as the group takes further musical steps, that can be a reference point. As has happened in the past with any performer, Miles started out playing a certain way and he evolved, but he gathered his audience in the beginning, and as he evolved, the reference point was the first point. It's just like arithmetic: you learn the first lesson, then you learn the second one, then the third. You might have a hard time jumping in there on the ninth lesson to begin with, without knowing the first lesson. That's not always the case, but once you can grab onto the moving train, you're on the train.

B.J.: Is there anything you want to say in closing? Anything you want to make sure we get in?

H.H.: Well, I guess the main thing is that jazz is not dead. The music has continued to evolve. I think it's better now than it's ever been—I really do.”