“Jarrett's spontaneous structuring of his music, his ability to incorporate and express basically European ideas in the jazz idiom, and the ecstatic heights to which he pushed his tone and melodies opened up new territory for other pianists to explore.”

- Len Lyons, Jazz author and record producer

“There are some simple virtues in his playing which any listener can surely respond to: gorgeous melodies, patiently evocative development which can lead to genuinely transcendent climaxes, beatific ballad playing. But it can be hard to tune out musical (and non-musical) matter which is likely to have dismayed as many as it has enraptured.”

- Richard Cook’s Jazz Encyclopedia

If I understand the situation correctly - there is so much rapidly transmitted misinformation these days - Keith Jarrett has been unable to perform since suffering a stroke in February 2018, and a second stroke in May 2018, which left him partially paralyzed and unable to play with his left hand.

Given this situation, I thought a look back to when it was first happening for Keith might be an interesting way to understand his Jazz Journey.

Most of this information and the actual interview itself are drawn from Len Lyons, The Great Jazz Pianists [DaCapo 1983].

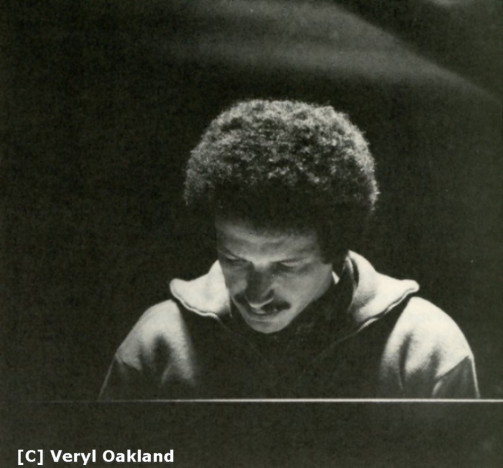

“During the 1970's Keith Jarrett was the enfant terrible of jazz piano. He commanded the highest fees ever for solo performances, many of which were staged at opera houses and concert halls that had previously been the exclusive turf of classical artists. He played the role of prima donna to the hilt, sometimes complaining to the audience that the piano or the sound system was inadequate. His smug, quasi-philosophical pronouncements, which might interrupt a concert at any time, elicited oohs and aahs from some fans but probably embarrassed those with less impressionable minds.

When Keith Jarrett played the piano, he broke every rule in the book of good form. Never mind hand position - he did not even sit down much of the time. In especially rhapsodic passages, which abound in his seamless improvised compositions, his genuflecting and gyrating in front of the keyboard made Elvis Presley look like a mannequin.

Nevertheless, Jarrett made the piano sing a new song, and nearly everybody loved it. No one did more to stimulate interest in jazz piano among a broad audience than Jarrett did in his decade of prominence. His Köln Concert album of lengthy solo improvisations was a major factor in establishing the viability of the ECM label. Its sales of a quarter million units or so revived confidence in the commercial potential of the piano in jazz. Most important, Jarrett's spontaneous structuring of his music, his ability to incorporate and express basically European ideas in the jazz idiom, and the ecstatic heights to which he pushed his tone and melodies opened up new territory for other pianists to explore.

One of five children, Jarrett began piano lessons at the age of three and was judged to be a prodigy by some of his teachers. At seventeen he enrolled in the Berklee College of Music in Boston, but he soon moved to New York, where he and his wife lived in Spanish Harlem. Keith studied drums and soprano saxophone, instruments he continues to use on records. A jam session at the Village Vanguard led to four months of work in 1965 with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. But Jarrett's passionate and soulful soloing ripened noticeably when he played with the Charles Lloyd Quartet (1966-69), one of the few jazz groups of the sixties to find a broad audience. With drummer Jack Dejohnette, his colleague from the Lloyd group, Jarrett joined Miles Davis's band in 1970. He formed his own quartet in 1972 with Dewey Redman on tenor sax, Charlie Haden on bass, and Paul Motian on drums.

Since 1973 Jarrett has maintained virtually three careers at once: bandleader, composer, and piano soloist. Inspired by diverse influences - Ornette Coleman, Bill Evans, Paul Bley, and modern classical music - Keith has synthesized his sources into a new and bold individuality- No other pianist has dared play entire concerts of spontaneous improvisations. Few could bring them off successfully if they tried.

The following conversation was taped in the general manager's office of KJAZ radio in Alameda, California. After an on-air interview, the customarily reticent Jarrett revealed his views on the piano, the creative process, and the subtle differences between composing and improvising.

How do you feel about the recent trend toward multiple keyboards?

The keyboard idea is one of the immense illusions in music at the moment. The keyboard is being used like a Parker Brothers game, a version of three-dimensional chess which they can sell to people who can't play two-dimensional chess. To simplify: People are making the problem of getting something out of themselves into an exterior problem of finding the right instruments to get it out with. It's like saying the reason I can't paint a masterpiece is that I don't have the right paints.

Should I infer that you don't think there's any good music being made on electric keyboards.?

You can infer that, but not from this. It's a matter of what electricity really is. The world is electric to begin with. The very fact that we move around is because of electric impulses, and we're not plugged in, so obviously there's a bigger kind of electricity than the kind you plug in. I live in the electric world, and making it electronic would be less strong.

You once said, "My first experience in composing involved adding a note to the last chord of a Mozart concerto," Is that composing or improvising? How do you distinguish between the two in terms of your solo concerts?

Well, there's no distinction between the two in the way I deal with it, although there are many differences in the two processes. You might call it spontaneous composition, which would connect the two. When you write something on paper, no matter how preconceived it is, it's still spontaneous because you can always change your mind when the pencil is about to touch

the paper. Even if you edit three hundred times, it's still spontaneous each time.

The difference for me is that when I'm composing, I can concentrate on each of the lines separately. See, no matter what anyone says, the human ear cannot hear more than two lines at the same time. As a composer, perhaps I can arrange them so the listener has the illusion he can hear all the lines. For example, there is a certain way of playing Bach's piano music when he has four lines going at once in which -if the timing is just off precision - you can hear each line more clearly. If you played them exactly as they were on paper with a metronome, you could hear only one line at a time. Your ear makes the choice. In improvising there's no time to deal with that. But there's a feeling you can get while improvising that makes up for that problem. You can do it spontaneously if you can sit far enough back from your own playing, if you don't identify with your own playing and are not what people call completely involved in your music. If you're aware of what you're playing as a listener, you're waiting to be able to distinguish all the lines. Then, as a player, you can give yourself that as a listener.

I had a hard time deciding whether "A Pagan Hymn" on In the Light was a spontaneous composition or written away from the piano.

It was composed completely away from the piano, but that's a good example of the distinction being blurred.

Where do you see yourself within the pianistic tradition? Do you feel influenced by bebop, stride, the romantic classics?

I rarely see myself as a continuation of a pianistic tradition, except to the extent that I use the piano. I have to identify myself with what the piano has made people aware of. If Chopin wrote piano music that no one conceived of before him, I must consider Chopin an influence. But I don't feel influenced by him musically to the extent that I feel like part of a tradition. In the case of jazz pianists, the tradition is improvisation. I was influenced by the need these people had to improvise - improvise something valuable enough to last for years and years.

Who are some of the improvisers that have impressed you?

The funny thing is that it's the process of improvising that impressed me. That's more important than the product. The people who influenced me were people I never heard, which may sound a little strange.

Yes, it does.

I once went to a "blindfold test" in Paris, and I knew who Bud Powell was, even though I never listened to his records. Well, maybe I heard them without realizing it.

Were there other pianists you recognized without ever hearing them before?

Yeah, there were. When I was at Berklee, someone said I sounded a lot like Bill Evans. I'd never heard him. See, the spirit that actually motivates music to come out of somebody has nothing to do with other musicians that have played before.

Do you think you'd play differently if you had been born one hundred years ago?

Of course, but the spirit would be the same. For that matter, I play differently in a basement from in an attic. But these are unconscious influences that are inescapable. I guess that's not what you had in mind.

Are there composers who have influenced your music?

Yes, but mostly because of what they were trying to do, not so much because of what they did. I feel very close to [Charles] Ives, and the reason is his supposed eccentricities, which were the only ways he could get out what he wanted to get out.

Your own piano playing technique is a bit eccentric, standing in front of the keyboard and so on. Is this a looseness you'd recommend? Do you recommend any particular way to acquire technique?

If someone studied piano playing by watching me play - or making films of my playing - he'd make a disastrous mistake. I play the way I do out of necessity, not because it's the best way in the world for anyone to play the piano. It's the only way I can get the piano to do what I want it to do. If I know what I want it to do, that's what's important.

I'd say anyone who wanted to play piano should start where the piano started in order to learn what people have done. Once they know what's been done, they're more capable of dealing with what they can hear. I don't know of many people who are as unaware of the tool they're using as pianists, which is reflected in the idea of keyboards. "A keyboard attached to a piece of wood that has strings on it and a cast-iron frame that goes out of tune more than they like" is probably what they know about it.

You've mentioned that the tone quality you're looking for can be elicited only from certain pianos. Which ones?

Hamburg Steinways. Occasionally the New York Steinway. The Bremen and Lausaune concerts were on seven-foot and nine-foot Steinways. I'd never do a group recording in a studio on a nine-foot Steinway. The Facing You album is on a five-foot-ten-inch Steinway.

You do get unique tone production, which seems characteristic of improvisers with a strong identity. Is there some way that tone can be worked on?

No, you don't work on that. You do the opposite. If you think about it,

you're making a mistake. That's what's happening all over in music. People are asking too many questions, thinking that the answer will be laid on them. You go to hear someone who knocks you out and then go backstage with some earthshaking question that will change your life, if someone answers it. I don't remember ever having those questions to ask of anybody, like: "How do you do this or that?" It's part of the exteriorization process - like electronic instruments. It's a guru thing. You try to find someone who'll tell you what you should have been doing when you weren't "in." Meanwhile, you stay "out," which makes it harder to get back "in," which is where you live.

That's going to make my next question suspicious, but I'll ask it anyway. Do you think playing directly on the piano's strings, as you did in Charles Lloyd's band, is an effect that can be cultivated and practiced?

No. I stopped doing it because I saw people taking it that way. It was just part of the music I was playing. Anything can be used - you can learn a whole new set of things to do on a piano. That's not the problem. The problem is why? Are you doing it because you can't do something else or because you have to do it? There's a difference. People I've heard playing on the strings now - it's not an organic part of their music. It's a divorced effect. When you don't know what else to do, you might do that.

Maybe it's a type of experimentation.

All the experimenting I've done is between concerts. I don't experiment when I play. Experimenting is practicing being conscious. I know I can be conscious when I'm playing music. Playing is the least important thing. It's the most important to the audience, but the least to the artist. It's the end product, and - this may sound negative, but I don't mean it that way - it could be called the waste product: the waste product of the activity of being musical, Being musical with a capital M could simply mean living a harmonious life with your own organism and projecting that to other people. That's why we need music. You can't project being in harmony with yourself without using a medium, and music is the medium which comes closest to showing it.

Do you listen to much music?

I do, although not a lot of music that's being played now. I know what's happening. I have a barometer inside me. I feel responsible for knowing what's going on, so I dip quickly into things that are happening now and wait for something to impress me. When it doesn't, I also feel responsible not to pretend.

What's your feeling about the music business?

I feel disassociated from any business. I deal with it as though I were into

it, but I'm not. I have a responsibility to my audience to make myself available somehow. If I have to do it by using the music business, I will in some ways. In other ways I won't. I won't go on the Johnny Carson show.

You have to draw the line somewhere.

The line comes a lot earlier than that.

Is there anything you'd like to express that we haven't covered?

Now that we're at the end, I'd like to say something about words. Everything I've said has been a response to something you've said or to the subject matter of the interview. It's not based on thinking I can transmit anything through words. The feeling I have at the end of every interview is: "I didn't say it!" because I can't say it in words.”

Selected Discography

Forest Flower: At Monterey (with Charles Lloyd, 1968); AT-1473; Atlantic.

Miles Davis: Live/Evil (1970); CG-30954: Columbia.

Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne (1973); 3-1035; ECM.

The Köln Concert (1975); 1064/65; ECM.

Concerts: Bremen/Munich (1981); 3-1227; ECM.

With Quartet:

Fort Yawuh; AS-9240; Impulse.

Backhand; ASD-9305; Impulse.

Survivors' Suite; 1-9084; ECM.