The following piece by David Hajdu was prepared for publication in 2009 so as to coincide with the 10th anniversary of Michel’s death. Other books by Mr. Hajdu include Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn and How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger.

In an effort to collect on the blog and its related Archive and Labels as much of the Jazz literature in English about Michel Petrucciani, the JazzProfiles editorial staff has posted Mr. Hajdu’s essay to compliment the series about Michel currently featuring on these pages.

It contains a number of critical insights into what made Petrucciani’s playing so distinctive and is an entertainingly written narrative.

Plus Michel Petrucciani – “Keys To the Kingdom”

by David Hajdu

The New Republic

Post Date Wednesday, March 18, 2009

© - David Hajdu, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“One grave away from Chopin and not far from Balzac and Jim Morrison in Pere-Lachaise, the Parisian cemetery and tourist hotspot, lies the French-Italian pianist Michel Petrucciani. He died ten years ago this January in New York, the city where he had made his reputation as a jazz tyro, and when his body was returned to France for his burial, thousands of mourners filled the streets of the 20th arrondissement. One of the French radio channels played no music but his for twenty-four hours. Chirac praised Petrucciani for his "passion, courage, and musical genius" and called him "an example for everyone."

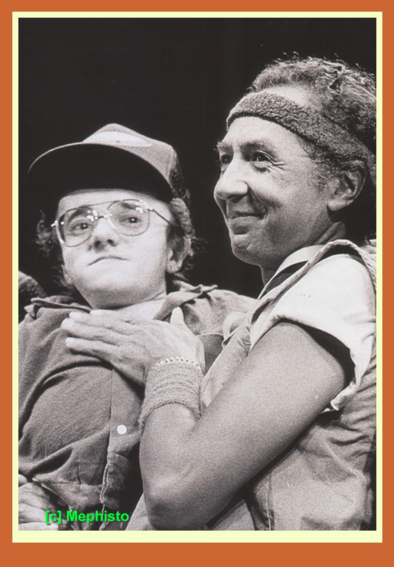

Of what, exactly, was Petrucciani an example? Chirac was no doubt referring to what he described, in proto-Oprahish terms, as Petrucciani's "courage"--the tenacity and the inclination to defiance which seemed, in Petrucciani, triumphs of the mind and the heart over the body. Petrucciani, a musician of rare power and expressive confidence, suffered--truly suffered, in lifelong pain--from osteogenesis imperfecta, the "glass bones" disease. For most of his thirty-six years, Petrucciani could not bear the weight of his own body without leg braces or crutches. He never grew past the height of three feet, and he typically weighed about fifty pounds. He was as fragile as his art was robust, his life as tenuous as his music is durable.

Over the course of this year, Dreyfus Jazz, the French-American label, will issue remastered, repackaged, and in most cases expanded versions of the ten albums that Petrucciani recorded for the label in his last years, as well as a two-DVD set of documentary and concert footage not previously released in this country. The series is an overdue reminder of the ecstatic power of Petrucciani's music. I cannot think of a jazz pianist since Petrucciani who plays with such exuberance and unashamed joy. Marcus Roberts and Michel Camilo have greater technique; Bill Charlap and Eric Reed, better control; Fred Hersch has broader emotional range; Uri Caine is more adventurous. Their music provides a wealth of rewards--but not the simple pleasure of Michel Petrucciani's. With the whole business of jazz so tentative today, you would think more musicians would express some of Petrucciani's happiness to be alive.

The power Petrucciani communicated, as a pianist, was the force of a will, a muscularity of the mind. He admired and emulated Duke Ellington, but had to simulate the effect Ellington and some other strong pianists have achieved by using more of their bodies than their hands. (Ellington, like Randy Weston today, put his lower arm weight into his playing to give it extra heft.) Petrucciani generated power through the speed of his attack. His force was willed; but, in the determined gleefulness of his playing, it never sounded forced.

Giddily free as an improviser, Petrucciani trusted his impulses. If he liked the sound of a note, he would drop a melody suddenly and just repeat that one note dozens of times. His music is enveloping: he lost himself in it, and it feels like a private place where strange things can safely ensue. Today, when so much jazz can sound cold and schematic, Petrucciani's music reminds us of the eloquence of unchecked emotion. "When I play, I play with my heart and my head and my spirit," Petrucciani once explained to an interviewer. "This doesn't have anything to do with how I look. That's how I am. I don't play to people's heads, but to their hearts. I like to create laughter and emotion from people--that's my way of working."

Born in Orange, near Avignon, in 1962, Petrucciani was raised in Montelimar. Essentially the Texas of France, Montelimar has a people who take fierce pride in their southern identity, distrust those northern elitists, speak with a twangy accent, and revel in the telling of tall tales. "Michel was really into bullshitting," remembers one of Petrucciani's friends, the French journalist Thierry Peremarti.”

Michel would lie to your face. That's one of the reasons he didn't get more press. He pissed off a lot of people. He was from the south--you talk, you talk, and you say nonsense." In 1980, Petrucciani told a People magazine reporter that he had raced Harleys with the Hell's Angels and had gone hang-gliding with eggs between his toes.

There are four categories of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a family of disorders involving genetic dysfunction in collagen production. The first is Type I, which is so subtle that it frequently goes unrecognized and untreated. Type II is the most severe, usually lethal upon birth; the victims' bones crumble at first touch. Petrucciani was born with a moderately acute kind of OI in a group overlapping Type III and Type IV: his bones were so weak that they fractured more than a hundred times during his childhood. Any kind of movement was difficult and usually painful. Petrucciani could not walk at all until adolescence, when his bones strengthened somewhat (like those of all teenagers, including OI sufferers). He had physical deformities typically associated with OI: distorted facial features, a protruding chin, bulging eyes, and curvature of the spine. In most cases like Petrucciani's, life span is diminished, and in those instances where the patients reach middle age, deafness usually occurs.

"He was in pain all the time," recalled his father, Tony Petrucciani, a part-time guitarist in the Grant Green mold. "He cried. I bought him a toy piano." The keyboard looked like a mouth to Michel, and he thought it was laughing at him, so he smashed it with a toy hammer, and his father got him an old full-size upright abandoned by British soldiers at a military base. From the age of four, Michel spent virtually all his free time, which was abundant, at the piano.

Petrucciani was twelve years old and looked like a toddler when his father started carrying him into jam sessions around the south of France. He was thirteen when he made his professional debut at the Cliousclat Festival in the southern district of Drome. "My European promoter told me, 'We got to do a tour with this little cat,'" remembers Clark Terry, the trumpeter. "I didn't believe him. When I heard him play--oh, man! He was a dwarf, but he played like a giant. I said, 'Listen, little guy--don't run away. I'll be back for you.'" Within two years, Petrucciani would be performing regularly in French jazz festivals, first with the expatriate American drummer Kenny Clarke and shortly after that with Terry.

During his first years performing and recording professionally, Petrucciani's specialty was youthful over-compensation. His piano playing, though already tinged with the romantic lyricism that would later distinguish it, tended toward defensive demonstrations of virtuoso technique and speed. Without having yet come to a mature understanding of what he wanted to say, he said little but did so really, really fast. He projected swaggering, roguish macho--a youngster's fantasy conception of continental virility. He called everybody "baby" and wore a yachtsman's cap. "He acted tough and pushy, and his playing was tough and pushy," says the writer and trombonist Michael Zwerin, who was living near Petrucciani and met him when the pianist was fifteen. "He knew how to say 'motherfucker' in French."

A fellow named Jean Roche lived near Zwerin and the Petruccianis, and he had experience with audio recording. (When Olivier Messiaen decided to experiment with bird sounds in his music, it was Roche who hid in trees and recorded the chirping.) Roche came into a bit of money and spent a sizable portion of it building a lavishly equipped recording studio near his home in the rural south. To give himself practice at engineering, Roche offered some nearby jazz musicians free access to the studio. Zwerin, Michel and his brother Louis Petrucciani (a bassist), and the French-Italian drummer Aldo Romano, who was vacationing at his parents' home nearby, spent most of a week there making Michel's first album, aptly titled Flash. "It's kind of sloppy and everything needs another take, but it swung, and it certainly shows off Michel well," says Zwerin, who served as titular leader of the sessions.

"We were sitting there wondering what to play," he remembers. "It was kind of hot. And Michel said, 'Anybody know "Giant Steps"?' Neither Louis nor I wanted to admit we didn't really know it. So there was this great silence. And Michel said, 'Well, I do!' And he pounded into a solo version of it at a very fast clip, and it was really amazing. That to me is Michel--'Well, I do!' Man, a confidence you wouldn't believe."

From the moment Petrucciani found he could excel at the piano, I think, what he could do overcame what he was as his source of identity. I play jazz piano, baby, and I do it faster and more fancily than anybody. I do, therefore it doesn't matter what I am.

Near the end of his life, Petrucciani looked back on his early career and called Aldo Romano his "guardian angel." The drummer, a generation older than Petrucciani, describes himself as Petrucciani's second father and remains proud of having helped Petrucciani pull away from the first one. "He wanted to see the world," recalls Romano. "But Michel was very fragile, and so everybody in his family was afraid. And also you have the problem of his father, because his father was an idiot. He didn't trust anybody. He wanted to keep him as a partner, to play music with. He was very jealous. So I had to fight to take him to Paris, because his father didn't want me to, because he wanted to keep him, like you would cage a monster."

After a brief visit to Paris and a return home in the autumn of 1980, Petrucciani moved into Aldo Romano's house in Bezons on the western perimeter of Paris and began his life as an adult professional. His music took on a new warmth and delicacy, a confidence in place of cockiness, and his grown-up personality--not just an emulation of his gangster heroes, but his own amalgam of southern French wile, musical sensitivity, and the bright, sparkling energy often associated with his genetic condition--began to emerge.

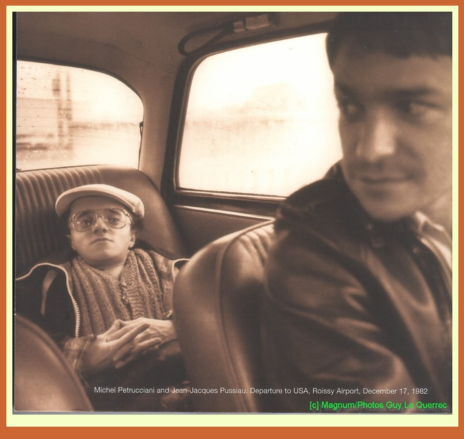

Petrucciani, who was always aware of the limited life span of OI sufferers, worked fast. Through an introduction by Romano, Petrucciani signed a recording contract with Owl Records, a French independent run by Jean-Jacques Pussiau, a former photographer, and he recorded six albums within three years. "He was always in a hurry," recalls Pussiau. "He said, 'Jean-Jacques, I don't want to lose time.'" The albums--especially the last two, Note 'n Notes and Cold Blues (both recorded in 1984)--are irresistibly precocious records, over-stuffed with ideas. Though most of this music is now difficult to find, there is an easy-to-get compilation of fifteen exemplary tracks, The Days of Wine and Roses: The Owl Years (1981-1985).

"We had an exceptional relationship," Pussiau says, "because I carried Michel in my arms very, very often. That creates a very strange intimacy. You know what it is to hold your child in your arms? I could feel his heart beating against my chest. I used to go on the stage and pick him up, and he was full of sweat. I would carry him away, and his sweat would soak through our shirts and onto my skin. Sometimes, when I used to carry him, he would bite my ear. We'd walk into a restaurant, and he'd chomp."

Petrucciani found success easily in France. "We did a tour together (in France), and the first place we played was packed," remembers Lee Konitz, with whom Petrucciani recorded a fine duet album, Toot Sweet, in 1982. "I said, 'Oh, man--my time has finally come.' Then I realized this little guy was the big attraction. He had just skyrocketed." The Petrucciani-Konitz duets, reissued here on the Sunnyside label, capture the maturing Petrucciani in a mode of harmonic exploration. That is to say, he is doing his best Bill Evans (especially on the first track, "I Hear a Rhapsody," which Evans himself had done as a duet, with the guitarist Jim Hall).

In 1981, Petrucciani had himself fitted for leg braces and crutches, rendering him independently ambulatory (at short distances) for the first time in his life, and he left for America, breaking away from both his family and Aldo Romano. "He didn't feel free with me," says Romano. "So he had to kill his second father somehow to move on. He needed to escape. He needed to go very far, as far as he could go, and that was California."

Petrucciani may or may not have stopped in Manhattan for a while. Although I have been unable to find anyone who actually saw him in New York this early, musicians have circulated stories that Petrucciani would tell about his first stint in the city. In one, he scammed his way to New York on bad checks, then had to hide out in Brooklyn with the help of Sicilian family connections. In another, he played piano for trade in a midtown brothel, where he learned the secrets of love. (Music-parlor prostitution in 1981? Where were the riverboat gamblers and runaway slaves?)

In Northern California, Petrucciani met his last mentor: Charles Lloyd, the saxophonist and self-styled mystic who had dropped out of the music scene for most of the previous decade. Petrucciani, then eighteen, visited Lloyd, then forty-three, at his house in Big Sur, and they began playing together. Lloyd decided to return to the road, with Petrucciani as his pianist. "Michel was like a son, and I loved him," Lloyd told me. "In his youthful innocence I recognized a quality one does not often find in another human being. Every inch of his small frame was filled with creativity and intelligence." Put another way, "Michel kicked Charles in the ass," says Peremarti. "Michel had something special, and Charles saw that right away. It made him pick up the saxophone."

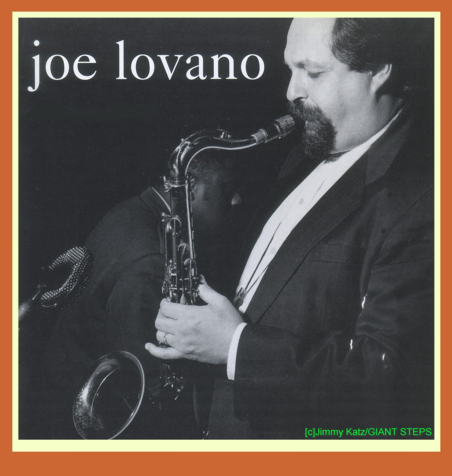

By late summer, in 1984, Petrucciani was ready for New York. "He was one of these total natural cats who could just sit and play with anybody, any time, any tune, whatever we were playing," recalls the saxophonist Joe Lovano. "Michel was the most magical cat I ever knew, man. When all the 'young lions' stuff was happening, Michel was the youngest, baddest lion out there. But because of his condition and he was from France or whatever, he didn't get tied in with all those cats, and he blew them all completely away."

The first time I saw Michel Petrucciani, a friend of his was carrying him into Bradley's, the tiny piano-jazz club in Greenwich Village where I spent most of my nights and salary in the 1980s. I had grown up in suburban New Jersey with a neighbor my age who had osteogenesis imperfecta. His name was Joey Bascai. His parents pulled him around in a wagon, but he used to like playing baseball. His father would pitch to him carefully, since a wild throw to his chest or head would have been devastating; he could swing the bat and do it well, and the rest of us kids would take turns as his runner. When I saw Petrucciani's friend walk past me with Petrucciani in his arms, I read all my old feelings about playing ball with Joey into his eyes: a vertiginous mixture of exhilaration in being part of the kicky little guy's fun and terror in the knowledge that it could end horribly in an instant. The bar crowd cleared a path from the door to the piano, and Petrucciani screamed, "Get out of my way, motherfuckers!"

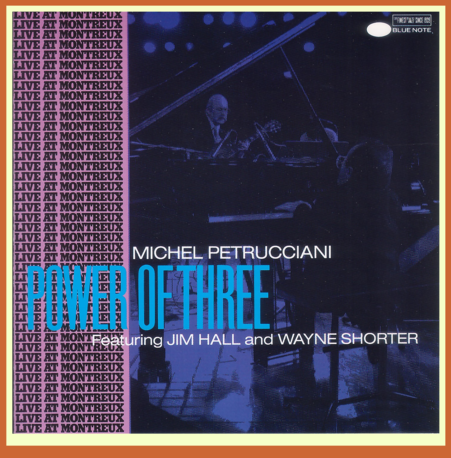

Over the next few years, I saw Petrucciani a dozen times at Bradley's and the Village Vanguard. He recorded roughly an album a year for Blue Note, including some gorgeous work with Wayne Shorter and Jim Hall. Power of Three, the trio album they recorded live in Montreux in 1986, may well be the most robustly emotive work of jazz recorded in the 1980s. Petrucciani's music had reached full bloom. He was improvising with loving, playful winks at every style from Harlem stride to free jazz, and he was composing tuneful, idiosyncratic pieces indebted but not wholly beholden to Monk and Ellington.

"I've never been around anyone who loved to live like Petrucciani--and live life to the fullest," says Mary-Ann Topper, his manager during his breakthrough years in New York. "He said to me, 'Mary-Ann, I want to have at least five women at once, I want to make a million dollars in one night' - things that were probably impossible. But had Michel ever thought that anything was impossible, he would have never done anything he did."

As Petrucciani himself said, "I'm a brat. My philosophy is to have a really good time and never let anything stop me from doing what I want to do. It's like driving a car, waiting for an accident. That's no way to drive a car. If you have an accident, you have an accident--c'est la vie." Fond of wine since his early adulthood in Paris, Petrucciani was now widely known to be drinking to excess and said to be enhancing his appetite for alcohol with cocaine.

In his last years, Petrucciani worked at a manic pace, performing more than a hundred solo piano concerts per year- 140 in 1998 alone. Too weak to stand with crutches, he was now using a wheelchair regularly. "He was working too much--not only recording and doing concerts, but he was always on television, and he was always doing interviews," recalls Bernard Ivain, Petrucciani's manager in his final years. "He got himself overworked, and you could see it. He pushed too much." Late in 1998, Petrucciani decided to slow down. "He couldn't keep up that pace anymore - he was physically exhausted," says Francois Zalacain. A few days into the new year, he was admitted to Beth Israel Hospital in New York, and he died there, of a pulmonary infection, on January 6, 1999.

Among the musicians Petrucciani phoned in his last days was Wayne Shorter. "He and I talked, and he said he comprehended that he was sick- that was an important thing," recalls Shorter. "There's a lot of people walking around, full-grown and so-called normal - they have everything that they were born with at the right leg length, arm length and stuff like that. They're symmetrical in every way, but they live their lives like they are armless, legless, brainless, and they live their life with blame. I never heard Michel complain about anything. Michel didn't look in the mirror and complain about what he saw. Michel was a great musician - a great musician - and great, ultimately, because he was a great human being, and he was a great human being because he had the ability to feel and give to others of that feeling, and he gave to others through his music. Anything else you can say about him is a formality. It's a technicality, and it doesn't mean anything to me."

David Hajdu is music critic for The New Republic.