- Steven Cerra [C] Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

If one can be said to have a genetic pre-disposition to Jazz, when my haploid genome got to the trombone part in its development, it probably found that it was already programmed to find the instrument agreeable because of my father’s love of Jack Teagarden.

For a man who had no formal musical training, my Dad could press the thumb and forefinger of his left-hand to his lips as though he was holding a mouthpiece in place, use the thumb and forefinger of the right to pantomime moving the trombone slide through various positions and accurately blurt out every note of Teagarden’s solos on St. James Infirmary, Rockin’ Chair and When It’s Sleep Time Down South.

I once met Jack in person at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival while he was fueling-up at the all-day buffet in the Viking Hotel which is located very near Freebody Park, the venue for the festival.

Much later, I would encounter this description of Jack Teagarden by Whitney Balliett from the Big T chapter in his American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz [New York: Oxford University Press, 1986] and reading it made me feel as though I was once again standing in Teagarden’s presence in 1956:

“Teagarden’s demeanor and appearance always belied his travails [he had been married four times, all relatively unsuccessfully; had no head for money and was a ‘gargantuan’ drunker]. He was tall and handsome, solid through the chest and shoulders. He had a square, open face and widely spaced eyes, which he kept narrowed, not letting too much of the world in at one time. His black hair was combed flat, its part just to the left of center. He was sometimes confused with Jack Dempsey.” [p. 161].

Gunther Schuller, in his essay entitled The Trombone in Jazz, a chapter in Bill Kirchner [ed.], The Oxford Companion to Jazz [New York: Oxford University Press, 2000] offers this assessment of what Jack Teagarden meant to Jazz trombone:

“Jack Teagarden brought a whole new level of musical sophistication and expressivity to trombone playing. By 1927, Teagarden had moved to New York, where he made his first recordings, amazing his fellow musicians with his versatility, original ideas, and profoundly moving ways of playing the blues.

Teagarden had a very easy, secure high register, and as a consequence was one of the first trombonists to develop and abundance of ‘unorthodox’ alternate slide positions, playing mostly on the upper partials of the harmonic series and thus rarely having to resort to the lower (fifth to seventh) positions. Since many of these alternate positions are impure in intonation, it is remarkable how in tune Teagarden’s playing was for that time.” [pp. 631-632; paragraphing modified].

As it turned out, it was the music from another day of the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival that figured directly into my introduction to the first of the two Jazz trombonists I came to prefer when I decided to purchase the Columbia LP [932; issued on disc as SME/SRCS 9522] that featured the Dave Brubeck Quartet and Jay and Kai at Newport.

Listening to the three tracks by the Jay and Kay Quintet on this LP, I “met” J.J. Johnson for the first time and it was love-at-bass-clef on my part. I had heard Kai Winding earlier on some Stan Kenton 78’s that a friend loaned me, but it was a new experience for me to hear his big, open sound in a small group setting.

Listening to the three tracks by the Jay and Kay Quintet on this LP, I “met” J.J. Johnson for the first time and it was love-at-bass-clef on my part. I had heard Kai Winding earlier on some Stan Kenton 78’s that a friend loaned me, but it was a new experience for me to hear his big, open sound in a small group setting.

Here’s what Günter Schuller has to say about the Kenton trombones and Kai Winding:

Here’s what Günter Schuller has to say about the Kenton trombones and Kai Winding:

“Another remarkable trombone section, totally different than Ellington’s was that of Stan Kenton’s orchestra. Beginning in the mid-1940s, its style initiated and set by Kai Winding, it revolutionized trombone playing stylistically, especially in terms of the sound (brassier, more prominent in the ensemble) and type of vibrato (slower, and mostly lack thereof), as well as by adding the ‘new sound’ of a bass trombone (Bart Vasolona and later George Roberts). The Kenton trombone section’s influence was enormous and continues to this day.

Although the section’s personnel changed often over the decades, it retained its astonishing stylistic consistency, not only because of stalwarts such as Milt Bernhart and Bob Fitzpatrick held long tenures in the orchestra, but because incoming players, such as Bob Burgess and Frank Rosolino and a host of others, were expected to fit into the by-then-famous Kenton brass sound.” [op. cit., p. 637; paragraphing modified].

Although the section’s personnel changed often over the decades, it retained its astonishing stylistic consistency, not only because of stalwarts such as Milt Bernhart and Bob Fitzpatrick held long tenures in the orchestra, but because incoming players, such as Bob Burgess and Frank Rosolino and a host of others, were expected to fit into the by-then-famous Kenton brass sound.” [op. cit., p. 637; paragraphing modified].

With the wonderful rhythm section of Dick Katz on piano, Bill Crow on bass and Rudy Collins on drums, both J.J. and Kai produced a brash, brassy, and vibrato-less sound on trombone that seem to leap out of the NJF recordings.

From what Willis Conover said when he introduced the Johnson-Winding band at the 1956 NJF, I gathered that this was one of the group’s last performance together. I was so excited by the two trombone sound that I searched out other recordings that the Jay and Kai Quintet had made during its existence from 1954-56.

A few years later, when my family moved to Southern California, I was introduced to the other half of my preferred Jazz trombone tandem when I visited The Lighthouse Café in Hermosa Beach, CA and I heard the inimitable Frank Rosolino perform as part of Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars [LHAS].

A few years later, when my family moved to Southern California, I was introduced to the other half of my preferred Jazz trombone tandem when I visited The Lighthouse Café in Hermosa Beach, CA and I heard the inimitable Frank Rosolino perform as part of Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars [LHAS].

Over the next two years, for the better part of 1958 through 1959, I was able to hear Frank five nights a week [with a double set on Sunday] with Bob Cooper [ts], Victor Feldman [piano and vibes], Howard Rumsey [bass] and Stan Levey [d] with Conte Candoli occasionally joining in to make it a sextet.

Frank and I hit it off right away because I knew that his last name was properly pronounced in Italian as “Rose-o-lino” and not the more customary English pronunciation of “Ross-o-lino.”]

It was not until much later that I came to understand J.J. Johnson’s place in the pantheon of be-bop gods as described in the following from Ira Gitler’s Jazz Masters of the 40s[New York: Da Capo, 1982]:

“As the BOP REVOLUTION spread, solo instruments other than the trumpet, alto sax, and piano began to echo the doctrines of Parker and Gillespie. The trombone, largely a rhythm instrument in the dawn of jazz before it was granted true solo privileges, had never been played in the swift, extremely legato, eighth-note style that J.J. Johnson introduced in the mid-forties. Since that time there have been few new trombonists who haven’t shown some manifestation of Johnson's style in their playing.

“As the BOP REVOLUTION spread, solo instruments other than the trumpet, alto sax, and piano began to echo the doctrines of Parker and Gillespie. The trombone, largely a rhythm instrument in the dawn of jazz before it was granted true solo privileges, had never been played in the swift, extremely legato, eighth-note style that J.J. Johnson introduced in the mid-forties. Since that time there have been few new trombonists who haven’t shown some manifestation of Johnson's style in their playing.

An innovator in areas of tone and technique, translator of bop ideas on his instrument, Johnson became the most influential and popular trombonist of the modem era. Whereas most of the giants of the forties were volatile personalities in one way or another, Johnson has always been soft-spoken, modest, and usually reserved, completely different in temperament from Gillespie, Parker, or Powell.” [p. 137]

But what I did know was how much I enjoyed listening to the sound that both J.J. and Frank produced on the trombone.

But what I did know was how much I enjoyed listening to the sound that both J.J. and Frank produced on the trombone.

As for Frank, I had vague remembrances of his playing with Kenton on Frank Speaking and I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good, but once again I was unaware of his ground-breaking significance concerning the instrument per the following quotation from trombonist, arranger and composer – Bill Russo – in Ted Gioia’s The History of Jazz, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997]:

“Crediting Rosolino for broadening the technique of the trombone, Bill Russo recalled: ‘We were all staggered by what he could do, not only at the speed of his technique and that he played so well in the upper register, but that he had such incredible flexibility.” [pp. 268-269].

More background about the development of Frank’s incredible facility on trombone can be found in the following from Ted Gioia, although the source for the citation changes to his West Coast Jazz, Modern Jazz in California: 1945-1960 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]:

More background about the development of Frank’s incredible facility on trombone can be found in the following from Ted Gioia, although the source for the citation changes to his West Coast Jazz, Modern Jazz in California: 1945-1960 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]:

"Rosolino was the son of immigrant parents from Sicily [my father who was from an area around Rome promised not to hold this against him!] who settled in Detroit, where Frank was born on August 20, 1926. His father, a talented musician who played mandolin, clarinet and guitar, started instructing him on guitar at age nine and encouraged him to study the accordion at thirteen. The old-country instrument did not appeal to the youngster. Instead, he convinced his father that he was big enough to learn the trombone. Beginning on a $25 model purchased at a pawnshop, Rosolino spent much of his practice time mimicking the exercises his brother Reso played on the violin. ‘Maybe that’s why I started thinking of playing with speed,' Rosolino later mused.” [pp. 221]

Over the years, as I heard Frank night after night with the LHAS, and later with the Terry Gibbs Dream Band at The Summit or with his own quartet with Victor Feldman on piano which appeared one night a week at Shelly’s Manne Hole, it became very easy to agree with the following assessment of Frank’s playing by Gene Lees in his Meet Me at Jim and Andy’s: Jazz Musicians and Their World [New York: Oxford University Press, 1988]:

“Frank Rosolino was … [o]ne of the finest trombone players in the history of the instrument, he had a superb tone, astonishing facility, a deep Italianate lyricism, and rich invention. Frank was very simply a sensational player. In addition he had a wonderful spirit that always communicated itself to his associates on the bandstand or the record date.” [p. 111].

Or as Bob Gordon succinctly phrased it in his Jazz West Coast: The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950s [London: Quartet Books, 1986]:

“… Frank Rosolino remains ‘sui generis,’ a trombonist with a truly unique style.” [p. 146].

And all this time, here I was messing around with these two trombonists having no idea that they were two giants; I just loved listening to them play.

Because of my proximity to Frank’s playing, J.J., who was based in New York at this time, kind of got pushed into the background a bit until one day when a copy of J.J. Inc [Columbia 1606] arrived at the door courtesy of the Columbia Record Club.

What an album! I still have the original LP and it is a miracle that it plays given the number of times a needle has cut through the vinyl.

What an album! I still have the original LP and it is a miracle that it plays given the number of times a needle has cut through the vinyl.

Of course, it has been subsequently supplanted by a CD [Columbia Legacy CK 65296] which much to my delight contains an extended version of one of the tracks that appeared on the original LP and two bonus tracks that were not included on the vinyl version.

And to say that as a result of this LP, J.J. was back in my life would be an understatement, because he brought along with him Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Cedar Walton on piano, before both joined Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Clifford Jordan on tenor saxophone, Arthur Harper on bass and the ever-pulsating Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums in what is perhaps the best recording Tootie ever made and he has made a lot of ‘em.

This recording offers J.J. Johnson at the peak of his form as a Jazz trombonist and it also shows his gifts as both a composer and a arranger as he wrote seven of its nine tracks and arranged all of them.

This recording is a composite snapshot of everything that was going on in the Jazz world of its time [1960/61] from the modal sounds of Miles’ Kind of Blue to the hard bop infusion of gospel and blues into bebop, to the ¾ time craze and minor harmonies preferred by the “My Favorite Things” John Coltrane quartet to the next generation of up-and-coming, front line soloists as represented by Hubbard, Jordan, Walton and Heath.

This recording is a composite snapshot of everything that was going on in the Jazz world of its time [1960/61] from the modal sounds of Miles’ Kind of Blue to the hard bop infusion of gospel and blues into bebop, to the ¾ time craze and minor harmonies preferred by the “My Favorite Things” John Coltrane quartet to the next generation of up-and-coming, front line soloists as represented by Hubbard, Jordan, Walton and Heath.

And what a perfect context for all of this material and personnel than to have as its leader – J.J. Johnson – to unify all of these elements and have them realize their potential.

Of the six tracks that comprised the original LP, Richard Cook and Brian Morton had this to say about Aquarius in their The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD: 6th Edition [New York: Penguin Books, 2002]:

“”Aquarius’ is the best evidence yet of J.J.’s great skills as a composer-arranger. As fellow-trombonist Steve Turre points out in a thoughtful liner-note to the augmented reissue, it’s a work that is almost orchestral in conception, making full-use of the three-horn front line, and also Walton’s elegant accompaniment. Brasses are pitched against saxophone and piano in a wonderful contrapuntal development, and ‘Tootie’ Heath gets a rich sound out of the kit.” [p. 800].

As Teo Macero points out in the liner notes to the LP, “When J.J. finished composing In Walked Horace, he exclaimed, ‘Look what I’ve done! It’s Horace Silver.’” The medium tempo tune is based on “Rhythm Changes” and contains the total surprise of Clifford Jordan taking over in the middle of a Freddie Hubbard chorus and continuing it as though nothing had happen! J.J.’s “solo” on the tune consists of trading 8’s, then 4’s, then 2’s and then 1’s with Tootie Heath before Cedar ends the soloing with one of his perfectly crafted solos based on evenly spaced eight-note phrases with more than their share of funk.

As Teo Macero points out in the liner notes to the LP, “When J.J. finished composing In Walked Horace, he exclaimed, ‘Look what I’ve done! It’s Horace Silver.’” The medium tempo tune is based on “Rhythm Changes” and contains the total surprise of Clifford Jordan taking over in the middle of a Freddie Hubbard chorus and continuing it as though nothing had happen! J.J.’s “solo” on the tune consists of trading 8’s, then 4’s, then 2’s and then 1’s with Tootie Heath before Cedar ends the soloing with one of his perfectly crafted solos based on evenly spaced eight-note phrases with more than their share of funk.

There are two versions of Fatback, a straight-ahead F blues with a slick head in 6/8 time that is punctuated by Tootie playing eight-note triplets on the cymbal along with a stiff back beat on the snare drum. Besides a cooking introduction by Cedar, the extended version of Fatback “… shows just how funky J.J. could be when he let go.” [Ibid]. In my opinion, this is the best extended solo that J.J. ever put on record; you’ll hear phrases and ideas on this track that he has never repeated on any other solo. He takes the opening solo so well that he inspires great performances from the other members of the band, including one with Freddie playing over stop time, as they all stretch out magnificently on this slow blues [Clifford Jordan’s tenor solo verges on being a ‘bar-walker’ in places!].

Minor Mist [named by a member of the audience at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco] is according to J.J. – “a dark pulse” [the ‘pulse’ part being reinforced by Tootie’s use of tympani mallets on tom toms.] It is held together by a vamp around which J.J. weaves its beautiful melody.

Shutterbug is an up-tempo minor blues written in a 20-bar form whose series of solos are separated by interludes that have the same rhythm [played in time], but are based on different harmonies. Tootie plays the “line” [melody] using the stick across the snare drum “knocking sound” on the 4th beat of each bar that Philly Joe Jones used to drive the original Milestones [on the Miles Davis Columbia album of the same name]. This cut will swing you into next week.

Written in 3/4 time, Mohawk, is a minor blues that was so named by J.J. after he wrote the tune because of “the Indian flavor in its harmony.”

Added to the augmented version that was released on CD are Dizzy Gillespie’s Blue ‘n Boogie, an up-tempo cooker and J.J.’s Turnpike both of which find all the members of the sextet in fine form. Each of these bonus tracks offer excellent, extended solos by J.J. who is obviously feeling very comfortable being backed by the Walton-Harper-Heath rhythm section. J.J.’s playing on these two tracks is ineffable and must be heard to be believed.

The best summary one could offer for J.J.’s music and playing on J.J. Inc. is contained in Steve Turre’s closing insert notes paragraph:

The best summary one could offer for J.J.’s music and playing on J.J. Inc. is contained in Steve Turre’s closing insert notes paragraph:

“There are many wonderful trombone players in America's classical music – jazz - and they have different areas of excellence that they bring to the music. The profundity of J.J. Johnson is that he is totally balanced in all areas - as a trombonist, as a musician and as a beautiful human being. (What you are as a person comes out of the horn in the music') He has no one area of excellence - at the expense of other areas. He has range both high and low, a huge sound, a flawless attack, dynamics. speed, swing and soul, and yet all these great powers are only used to serve the music. They are never used superficially for their own sake. He did for the trombone what Charlie Parker did for the saxophone. He brought the trombone into the modern world with a unique conception that affected all those who came after him and set the standard that is yet to be matched. He still "Chairman of the Board" and I love him and thank him all the beautiful music, inspiration and guidance.”

In the late 1950’s, listening to Frank Rosolino play trombone night after night at the Lighthouse, and later at other venues in and around Hollywood, was an experience I’ll never forget. The man was a phenomenally inventive instrumentalist.

In the late 1950’s, listening to Frank Rosolino play trombone night after night at the Lighthouse, and later at other venues in and around Hollywood, was an experience I’ll never forget. The man was a phenomenally inventive instrumentalist.

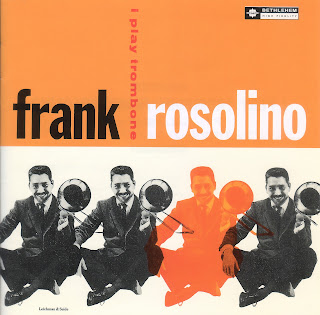

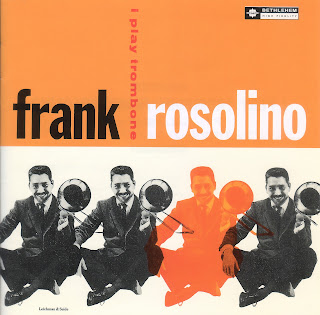

Aside from the Mode-LP # 107 pictured above [which has some splendid tenor sax playing by Richie Kamuca on it], I also possessed copies of his two, not-easy-to-find Bethlehem LP’s, I Play Trombone: Frank Rosolino [BCP -26; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62051] with the marvelous Sonny Clark on piano,

and the Russ Garcia arranged Four Horns and a Lush Life [BCP-46; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62052],

and the Russ Garcia arranged Four Horns and a Lush Life [BCP-46; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62052],

Although I did not own any of them at the time, I was even fortunate enough to hear some of the 10” and 12” LP’s that Frank recorded for Capitol under the “Kenton Presents Jazz” banner all of which have been collected and subsequently released as Mosaic Records MD4-185:

Although I did not own any of them at the time, I was even fortunate enough to hear some of the 10” and 12” LP’s that Frank recorded for Capitol under the “Kenton Presents Jazz” banner all of which have been collected and subsequently released as Mosaic Records MD4-185:

With outstanding arrangements by Bill Holman, trumpeter Sam Noto and alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano joining Frank on the front line and a brilliant rhythm section of Pete Jolly [p], Max Bennett [b] and Mel Lewis [d], it is regrettable that these recordings didn’t have a wider distribution thus giving Frank a greater national exposure.

With outstanding arrangements by Bill Holman, trumpeter Sam Noto and alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano joining Frank on the front line and a brilliant rhythm section of Pete Jolly [p], Max Bennett [b] and Mel Lewis [d], it is regrettable that these recordings didn’t have a wider distribution thus giving Frank a greater national exposure.

When the music was ultimately released as the album Free for All [Specialty SP 2161; OJCCD- 1763-2, Leonard Feather commented in the original liner notes:“The existence of the present volume was unknown except to those who had taken part in it – and, particularly, the man who produced it, David Axelrod. ‘Frank and I were excited about this album,’ Axelrod recalls, ‘because it was going to be the first hard bop album recorded and released on the West Coast. We wanted to get away from that bland, stereotyped West Coast image. We worked for weeks on planning the personnel and the songs; the results were terrific. It was a great disappointment to us both that the record, for reasons which we never understood, wasn’t released.’”

When the music was ultimately released as the album Free for All [Specialty SP 2161; OJCCD- 1763-2, Leonard Feather commented in the original liner notes:“The existence of the present volume was unknown except to those who had taken part in it – and, particularly, the man who produced it, David Axelrod. ‘Frank and I were excited about this album,’ Axelrod recalls, ‘because it was going to be the first hard bop album recorded and released on the West Coast. We wanted to get away from that bland, stereotyped West Coast image. We worked for weeks on planning the personnel and the songs; the results were terrific. It was a great disappointment to us both that the record, for reasons which we never understood, wasn’t released.’”

While taking some exception to the claim about the first hard bop album on the West Coast [and deservedly so as he notes the pioneering work in this regard by Clifford Brown, Curtis Counce and Harold Land], Ted Gioia in West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-60 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992] goes on the state:

“With a strong supporting band of composed of Harold Land, Stan Levey, Leroy Vinnegar and Victor Feldman, Rosolino created some of his finest work of the decade. The arrangements are well crafted; familiar standards such as ‘Star Dust’ and … [‘Love for Sale’] take on a new luster through provocative tempo and rhythm changes.” [p. 221].

Love for Sale opens the album with the melody played behind Stan Levey’s 6/8 Latin figure that resolves into a wickedly fast, double-timed 4/4 bridge. The blowing takes place in a slower, medium tempo and Frank’s and Harold Land’s solos "… establish immediately that this is a tough, no-holds-barred blowing session” [Leonard Feather’s liner notes].

Love for Sale opens the album with the melody played behind Stan Levey’s 6/8 Latin figure that resolves into a wickedly fast, double-timed 4/4 bridge. The blowing takes place in a slower, medium tempo and Frank’s and Harold Land’s solos "… establish immediately that this is a tough, no-holds-barred blowing session” [Leonard Feather’s liner notes].

A similar, finger-popping medium tempo is employed on Chrisdee an original by drummer Levey whose foot sounds like it’s going to snap through the high-hat pedal as he emphatically shows the soloists where 2 and 4 are and “don’t you dare try to speed this thing up.” It has been said of Levey that when he was playing time you can set your watch to it and this cut is a perfect example of that truism. The tune “… is a bebop line based on a cycle of fifths, with a somewhat Monkish bridge.” [Feather]

The ballad Twilight is an original Victor Feldman composition that also puts on display his skills as an arranger as there is no improvisation until Land begins a solo well into the tune. Frank plays the “beguilingly pensive” melody with Land sounding the chord root in the background over Feldman’s full chording and comping. It is a stunningly beautiful piece. Star Dust is the other ballad featured on the album.

The title track Free for All is a 24-bar blues original by Rosolino on which he employs his considerable arsenal of trombone techniques [including effortless sounding triple-tongued licks] to demonstrate that he really can play the blues. Land and Feldman join in for a few choruses to demonstrated that they too are card-carrying members and the chart comes to a close with a surprise ending!

There is No Greater Love is played in unison by the horns and taken at a crisp tempo that shows how wonderfully well Levey and Vinnegar work together and why the tune has been a jam session stand-by ever since it was written in 1956. The tunes chords “lay” so easily so as to make all of the solos sound effortless and uncontrived.

Sneakyoso is a Rosolino original that Leonard Feather describes as offering the quintet “an ingenious vehicle, its attractive changes providing good opportunities for Frank to work out. Note the fine comping Victor furnishes for Harold Land before taking over for his own solo. The two horns engage with Stan Levey before the head returns.”

As was the case with most of his recorded output, Frank was always interested in tempo and harmony changes to help the music sound fresh and new, and this is no less the case with everything that appears on Free for All.

Paired with J.J. Inc, I can think of no finer recording than Free for All to recommend to anyone wishing to hear the best of J.J. and Frank at work.

Many years later, after all of the East Coast versus West Coast nonsense had died down, I saw J.J. [who had, by then, been in Hollywood for a number of years writing for TV and the movies] sitting with Frank at Donte’s, a Jazz club and musicians hang-out in North Hollywood, CA. It was early in the evening before the set began and the two were having a quiet dinner together.

Many years later, after all of the East Coast versus West Coast nonsense had died down, I saw J.J. [who had, by then, been in Hollywood for a number of years writing for TV and the movies] sitting with Frank at Donte’s, a Jazz club and musicians hang-out in North Hollywood, CA. It was early in the evening before the set began and the two were having a quiet dinner together.

I must admit to not thinking very much about it at the time, after all, given the number of TV, motion picture and recording studios located there, musicians having a meal or a drink together in Hollywood and its environs is a common enough occurrence.

Also, since that occasion, and especially after 1978, it was always difficult for me to think about Frank and his music, given the tragedy associated with his death. Matters weren’t help much in this regard with the news of J.J.’s suicide in 2001 after a protracted struggle with cancer.

However, some 30 years later, I came across the following quotation from J.J. and it helped me to recall the memory of that quiet dinner meeting and reminded me of how much I loved the playing of both of these trombone giants. That memory and this quotation prompted me to write this piece as a loving tribute to both of them:

“Frank Rosolino was a towering genius and a trombone virtuoso in the jazz genre. His style was unique and instantly recognizable. He was a warm, fun loving, charming human being and I miss his infectious giggle.”

If one can be said to have a genetic pre-disposition to Jazz, when my haploid genome got to the trombone part in its development, it probably found that it was already programmed to find the instrument agreeable because of my father’s love of Jack Teagarden.

For a man who had no formal musical training, my Dad could press the thumb and forefinger of his left-hand to his lips as though he was holding a mouthpiece in place, use the thumb and forefinger of the right to pantomime moving the trombone slide through various positions and accurately blurt out every note of Teagarden’s solos on St. James Infirmary, Rockin’ Chair and When It’s Sleep Time Down South.

I once met Jack in person at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival while he was fueling-up at the all-day buffet in the Viking Hotel which is located very near Freebody Park, the venue for the festival.

Much later, I would encounter this description of Jack Teagarden by Whitney Balliett from the Big T chapter in his American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz [New York: Oxford University Press, 1986] and reading it made me feel as though I was once again standing in Teagarden’s presence in 1956:

“Teagarden’s demeanor and appearance always belied his travails [he had been married four times, all relatively unsuccessfully; had no head for money and was a ‘gargantuan’ drunker]. He was tall and handsome, solid through the chest and shoulders. He had a square, open face and widely spaced eyes, which he kept narrowed, not letting too much of the world in at one time. His black hair was combed flat, its part just to the left of center. He was sometimes confused with Jack Dempsey.” [p. 161].

Gunther Schuller, in his essay entitled The Trombone in Jazz, a chapter in Bill Kirchner [ed.], The Oxford Companion to Jazz [New York: Oxford University Press, 2000] offers this assessment of what Jack Teagarden meant to Jazz trombone:

“Jack Teagarden brought a whole new level of musical sophistication and expressivity to trombone playing. By 1927, Teagarden had moved to New York, where he made his first recordings, amazing his fellow musicians with his versatility, original ideas, and profoundly moving ways of playing the blues.

Teagarden had a very easy, secure high register, and as a consequence was one of the first trombonists to develop and abundance of ‘unorthodox’ alternate slide positions, playing mostly on the upper partials of the harmonic series and thus rarely having to resort to the lower (fifth to seventh) positions. Since many of these alternate positions are impure in intonation, it is remarkable how in tune Teagarden’s playing was for that time.” [pp. 631-632; paragraphing modified].

As it turned out, it was the music from another day of the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival that figured directly into my introduction to the first of the two Jazz trombonists I came to prefer when I decided to purchase the Columbia LP [932; issued on disc as SME/SRCS 9522] that featured the Dave Brubeck Quartet and Jay and Kai at Newport.

Listening to the three tracks by the Jay and Kay Quintet on this LP, I “met” J.J. Johnson for the first time and it was love-at-bass-clef on my part. I had heard Kai Winding earlier on some Stan Kenton 78’s that a friend loaned me, but it was a new experience for me to hear his big, open sound in a small group setting.

Listening to the three tracks by the Jay and Kay Quintet on this LP, I “met” J.J. Johnson for the first time and it was love-at-bass-clef on my part. I had heard Kai Winding earlier on some Stan Kenton 78’s that a friend loaned me, but it was a new experience for me to hear his big, open sound in a small group setting. Here’s what Günter Schuller has to say about the Kenton trombones and Kai Winding:

Here’s what Günter Schuller has to say about the Kenton trombones and Kai Winding:“Another remarkable trombone section, totally different than Ellington’s was that of Stan Kenton’s orchestra. Beginning in the mid-1940s, its style initiated and set by Kai Winding, it revolutionized trombone playing stylistically, especially in terms of the sound (brassier, more prominent in the ensemble) and type of vibrato (slower, and mostly lack thereof), as well as by adding the ‘new sound’ of a bass trombone (Bart Vasolona and later George Roberts). The Kenton trombone section’s influence was enormous and continues to this day.

Although the section’s personnel changed often over the decades, it retained its astonishing stylistic consistency, not only because of stalwarts such as Milt Bernhart and Bob Fitzpatrick held long tenures in the orchestra, but because incoming players, such as Bob Burgess and Frank Rosolino and a host of others, were expected to fit into the by-then-famous Kenton brass sound.” [op. cit., p. 637; paragraphing modified].

Although the section’s personnel changed often over the decades, it retained its astonishing stylistic consistency, not only because of stalwarts such as Milt Bernhart and Bob Fitzpatrick held long tenures in the orchestra, but because incoming players, such as Bob Burgess and Frank Rosolino and a host of others, were expected to fit into the by-then-famous Kenton brass sound.” [op. cit., p. 637; paragraphing modified].With the wonderful rhythm section of Dick Katz on piano, Bill Crow on bass and Rudy Collins on drums, both J.J. and Kai produced a brash, brassy, and vibrato-less sound on trombone that seem to leap out of the NJF recordings.

From what Willis Conover said when he introduced the Johnson-Winding band at the 1956 NJF, I gathered that this was one of the group’s last performance together. I was so excited by the two trombone sound that I searched out other recordings that the Jay and Kai Quintet had made during its existence from 1954-56.

A few years later, when my family moved to Southern California, I was introduced to the other half of my preferred Jazz trombone tandem when I visited The Lighthouse Café in Hermosa Beach, CA and I heard the inimitable Frank Rosolino perform as part of Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars [LHAS].

A few years later, when my family moved to Southern California, I was introduced to the other half of my preferred Jazz trombone tandem when I visited The Lighthouse Café in Hermosa Beach, CA and I heard the inimitable Frank Rosolino perform as part of Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars [LHAS].Over the next two years, for the better part of 1958 through 1959, I was able to hear Frank five nights a week [with a double set on Sunday] with Bob Cooper [ts], Victor Feldman [piano and vibes], Howard Rumsey [bass] and Stan Levey [d] with Conte Candoli occasionally joining in to make it a sextet.

Frank and I hit it off right away because I knew that his last name was properly pronounced in Italian as “Rose-o-lino” and not the more customary English pronunciation of “Ross-o-lino.”]

It was not until much later that I came to understand J.J. Johnson’s place in the pantheon of be-bop gods as described in the following from Ira Gitler’s Jazz Masters of the 40s[New York: Da Capo, 1982]:

“As the BOP REVOLUTION spread, solo instruments other than the trumpet, alto sax, and piano began to echo the doctrines of Parker and Gillespie. The trombone, largely a rhythm instrument in the dawn of jazz before it was granted true solo privileges, had never been played in the swift, extremely legato, eighth-note style that J.J. Johnson introduced in the mid-forties. Since that time there have been few new trombonists who haven’t shown some manifestation of Johnson's style in their playing.

“As the BOP REVOLUTION spread, solo instruments other than the trumpet, alto sax, and piano began to echo the doctrines of Parker and Gillespie. The trombone, largely a rhythm instrument in the dawn of jazz before it was granted true solo privileges, had never been played in the swift, extremely legato, eighth-note style that J.J. Johnson introduced in the mid-forties. Since that time there have been few new trombonists who haven’t shown some manifestation of Johnson's style in their playing.An innovator in areas of tone and technique, translator of bop ideas on his instrument, Johnson became the most influential and popular trombonist of the modem era. Whereas most of the giants of the forties were volatile personalities in one way or another, Johnson has always been soft-spoken, modest, and usually reserved, completely different in temperament from Gillespie, Parker, or Powell.” [p. 137]

But what I did know was how much I enjoyed listening to the sound that both J.J. and Frank produced on the trombone.

But what I did know was how much I enjoyed listening to the sound that both J.J. and Frank produced on the trombone.As for Frank, I had vague remembrances of his playing with Kenton on Frank Speaking and I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good, but once again I was unaware of his ground-breaking significance concerning the instrument per the following quotation from trombonist, arranger and composer – Bill Russo – in Ted Gioia’s The History of Jazz, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997]:

“Crediting Rosolino for broadening the technique of the trombone, Bill Russo recalled: ‘We were all staggered by what he could do, not only at the speed of his technique and that he played so well in the upper register, but that he had such incredible flexibility.” [pp. 268-269].

More background about the development of Frank’s incredible facility on trombone can be found in the following from Ted Gioia, although the source for the citation changes to his West Coast Jazz, Modern Jazz in California: 1945-1960 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]:

More background about the development of Frank’s incredible facility on trombone can be found in the following from Ted Gioia, although the source for the citation changes to his West Coast Jazz, Modern Jazz in California: 1945-1960 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992]:"Rosolino was the son of immigrant parents from Sicily [my father who was from an area around Rome promised not to hold this against him!] who settled in Detroit, where Frank was born on August 20, 1926. His father, a talented musician who played mandolin, clarinet and guitar, started instructing him on guitar at age nine and encouraged him to study the accordion at thirteen. The old-country instrument did not appeal to the youngster. Instead, he convinced his father that he was big enough to learn the trombone. Beginning on a $25 model purchased at a pawnshop, Rosolino spent much of his practice time mimicking the exercises his brother Reso played on the violin. ‘Maybe that’s why I started thinking of playing with speed,' Rosolino later mused.” [pp. 221]

Over the years, as I heard Frank night after night with the LHAS, and later with the Terry Gibbs Dream Band at The Summit or with his own quartet with Victor Feldman on piano which appeared one night a week at Shelly’s Manne Hole, it became very easy to agree with the following assessment of Frank’s playing by Gene Lees in his Meet Me at Jim and Andy’s: Jazz Musicians and Their World [New York: Oxford University Press, 1988]:

“Frank Rosolino was … [o]ne of the finest trombone players in the history of the instrument, he had a superb tone, astonishing facility, a deep Italianate lyricism, and rich invention. Frank was very simply a sensational player. In addition he had a wonderful spirit that always communicated itself to his associates on the bandstand or the record date.” [p. 111].

Or as Bob Gordon succinctly phrased it in his Jazz West Coast: The Los Angeles Jazz Scene of the 1950s [London: Quartet Books, 1986]:

“… Frank Rosolino remains ‘sui generis,’ a trombonist with a truly unique style.” [p. 146].

And all this time, here I was messing around with these two trombonists having no idea that they were two giants; I just loved listening to them play.

Because of my proximity to Frank’s playing, J.J., who was based in New York at this time, kind of got pushed into the background a bit until one day when a copy of J.J. Inc [Columbia 1606] arrived at the door courtesy of the Columbia Record Club.

What an album! I still have the original LP and it is a miracle that it plays given the number of times a needle has cut through the vinyl.

What an album! I still have the original LP and it is a miracle that it plays given the number of times a needle has cut through the vinyl.Of course, it has been subsequently supplanted by a CD [Columbia Legacy CK 65296] which much to my delight contains an extended version of one of the tracks that appeared on the original LP and two bonus tracks that were not included on the vinyl version.

And to say that as a result of this LP, J.J. was back in my life would be an understatement, because he brought along with him Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Cedar Walton on piano, before both joined Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Clifford Jordan on tenor saxophone, Arthur Harper on bass and the ever-pulsating Albert “Tootie” Heath on drums in what is perhaps the best recording Tootie ever made and he has made a lot of ‘em.

This recording offers J.J. Johnson at the peak of his form as a Jazz trombonist and it also shows his gifts as both a composer and a arranger as he wrote seven of its nine tracks and arranged all of them.

This recording is a composite snapshot of everything that was going on in the Jazz world of its time [1960/61] from the modal sounds of Miles’ Kind of Blue to the hard bop infusion of gospel and blues into bebop, to the ¾ time craze and minor harmonies preferred by the “My Favorite Things” John Coltrane quartet to the next generation of up-and-coming, front line soloists as represented by Hubbard, Jordan, Walton and Heath.

This recording is a composite snapshot of everything that was going on in the Jazz world of its time [1960/61] from the modal sounds of Miles’ Kind of Blue to the hard bop infusion of gospel and blues into bebop, to the ¾ time craze and minor harmonies preferred by the “My Favorite Things” John Coltrane quartet to the next generation of up-and-coming, front line soloists as represented by Hubbard, Jordan, Walton and Heath.And what a perfect context for all of this material and personnel than to have as its leader – J.J. Johnson – to unify all of these elements and have them realize their potential.

Of the six tracks that comprised the original LP, Richard Cook and Brian Morton had this to say about Aquarius in their The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD: 6th Edition [New York: Penguin Books, 2002]:

“”Aquarius’ is the best evidence yet of J.J.’s great skills as a composer-arranger. As fellow-trombonist Steve Turre points out in a thoughtful liner-note to the augmented reissue, it’s a work that is almost orchestral in conception, making full-use of the three-horn front line, and also Walton’s elegant accompaniment. Brasses are pitched against saxophone and piano in a wonderful contrapuntal development, and ‘Tootie’ Heath gets a rich sound out of the kit.” [p. 800].

As Teo Macero points out in the liner notes to the LP, “When J.J. finished composing In Walked Horace, he exclaimed, ‘Look what I’ve done! It’s Horace Silver.’” The medium tempo tune is based on “Rhythm Changes” and contains the total surprise of Clifford Jordan taking over in the middle of a Freddie Hubbard chorus and continuing it as though nothing had happen! J.J.’s “solo” on the tune consists of trading 8’s, then 4’s, then 2’s and then 1’s with Tootie Heath before Cedar ends the soloing with one of his perfectly crafted solos based on evenly spaced eight-note phrases with more than their share of funk.

As Teo Macero points out in the liner notes to the LP, “When J.J. finished composing In Walked Horace, he exclaimed, ‘Look what I’ve done! It’s Horace Silver.’” The medium tempo tune is based on “Rhythm Changes” and contains the total surprise of Clifford Jordan taking over in the middle of a Freddie Hubbard chorus and continuing it as though nothing had happen! J.J.’s “solo” on the tune consists of trading 8’s, then 4’s, then 2’s and then 1’s with Tootie Heath before Cedar ends the soloing with one of his perfectly crafted solos based on evenly spaced eight-note phrases with more than their share of funk.There are two versions of Fatback, a straight-ahead F blues with a slick head in 6/8 time that is punctuated by Tootie playing eight-note triplets on the cymbal along with a stiff back beat on the snare drum. Besides a cooking introduction by Cedar, the extended version of Fatback “… shows just how funky J.J. could be when he let go.” [Ibid]. In my opinion, this is the best extended solo that J.J. ever put on record; you’ll hear phrases and ideas on this track that he has never repeated on any other solo. He takes the opening solo so well that he inspires great performances from the other members of the band, including one with Freddie playing over stop time, as they all stretch out magnificently on this slow blues [Clifford Jordan’s tenor solo verges on being a ‘bar-walker’ in places!].

Minor Mist [named by a member of the audience at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco] is according to J.J. – “a dark pulse” [the ‘pulse’ part being reinforced by Tootie’s use of tympani mallets on tom toms.] It is held together by a vamp around which J.J. weaves its beautiful melody.

Shutterbug is an up-tempo minor blues written in a 20-bar form whose series of solos are separated by interludes that have the same rhythm [played in time], but are based on different harmonies. Tootie plays the “line” [melody] using the stick across the snare drum “knocking sound” on the 4th beat of each bar that Philly Joe Jones used to drive the original Milestones [on the Miles Davis Columbia album of the same name]. This cut will swing you into next week.

Written in 3/4 time, Mohawk, is a minor blues that was so named by J.J. after he wrote the tune because of “the Indian flavor in its harmony.”

Added to the augmented version that was released on CD are Dizzy Gillespie’s Blue ‘n Boogie, an up-tempo cooker and J.J.’s Turnpike both of which find all the members of the sextet in fine form. Each of these bonus tracks offer excellent, extended solos by J.J. who is obviously feeling very comfortable being backed by the Walton-Harper-Heath rhythm section. J.J.’s playing on these two tracks is ineffable and must be heard to be believed.

The best summary one could offer for J.J.’s music and playing on J.J. Inc. is contained in Steve Turre’s closing insert notes paragraph:

The best summary one could offer for J.J.’s music and playing on J.J. Inc. is contained in Steve Turre’s closing insert notes paragraph:“There are many wonderful trombone players in America's classical music – jazz - and they have different areas of excellence that they bring to the music. The profundity of J.J. Johnson is that he is totally balanced in all areas - as a trombonist, as a musician and as a beautiful human being. (What you are as a person comes out of the horn in the music') He has no one area of excellence - at the expense of other areas. He has range both high and low, a huge sound, a flawless attack, dynamics. speed, swing and soul, and yet all these great powers are only used to serve the music. They are never used superficially for their own sake. He did for the trombone what Charlie Parker did for the saxophone. He brought the trombone into the modern world with a unique conception that affected all those who came after him and set the standard that is yet to be matched. He still "Chairman of the Board" and I love him and thank him all the beautiful music, inspiration and guidance.”

In the late 1950’s, listening to Frank Rosolino play trombone night after night at the Lighthouse, and later at other venues in and around Hollywood, was an experience I’ll never forget. The man was a phenomenally inventive instrumentalist.

In the late 1950’s, listening to Frank Rosolino play trombone night after night at the Lighthouse, and later at other venues in and around Hollywood, was an experience I’ll never forget. The man was a phenomenally inventive instrumentalist.Aside from the Mode-LP # 107 pictured above [which has some splendid tenor sax playing by Richie Kamuca on it], I also possessed copies of his two, not-easy-to-find Bethlehem LP’s, I Play Trombone: Frank Rosolino [BCP -26; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62051] with the marvelous Sonny Clark on piano,

and the Russ Garcia arranged Four Horns and a Lush Life [BCP-46; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62052],

and the Russ Garcia arranged Four Horns and a Lush Life [BCP-46; released as a Japanese CD by Toshiba-EMI, TOCJ-62052], Although I did not own any of them at the time, I was even fortunate enough to hear some of the 10” and 12” LP’s that Frank recorded for Capitol under the “Kenton Presents Jazz” banner all of which have been collected and subsequently released as Mosaic Records MD4-185:

Although I did not own any of them at the time, I was even fortunate enough to hear some of the 10” and 12” LP’s that Frank recorded for Capitol under the “Kenton Presents Jazz” banner all of which have been collected and subsequently released as Mosaic Records MD4-185: With outstanding arrangements by Bill Holman, trumpeter Sam Noto and alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano joining Frank on the front line and a brilliant rhythm section of Pete Jolly [p], Max Bennett [b] and Mel Lewis [d], it is regrettable that these recordings didn’t have a wider distribution thus giving Frank a greater national exposure.

With outstanding arrangements by Bill Holman, trumpeter Sam Noto and alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano joining Frank on the front line and a brilliant rhythm section of Pete Jolly [p], Max Bennett [b] and Mel Lewis [d], it is regrettable that these recordings didn’t have a wider distribution thus giving Frank a greater national exposure.

But it was through an association that I had with pianist-vibist [and drummer] Vic Feldman that I kept hearing about the “Wait until you hear Frank on the date we just did with Harold Land and Stan Levey.” Victor was an unassuming and understated fellow who took his own talents for granted and didn’t throw around praise lightly, if at all. So when he got excited you just knew it had to be over something very special.

Unfortunately, it was to be a long wait, for although the music in question had been recorded in December of 1958, it wasn’t released until 1986, eight years after Frank’s death.

Unfortunately, it was to be a long wait, for although the music in question had been recorded in December of 1958, it wasn’t released until 1986, eight years after Frank’s death.

When the music was ultimately released as the album Free for All [Specialty SP 2161; OJCCD- 1763-2, Leonard Feather commented in the original liner notes:“The existence of the present volume was unknown except to those who had taken part in it – and, particularly, the man who produced it, David Axelrod. ‘Frank and I were excited about this album,’ Axelrod recalls, ‘because it was going to be the first hard bop album recorded and released on the West Coast. We wanted to get away from that bland, stereotyped West Coast image. We worked for weeks on planning the personnel and the songs; the results were terrific. It was a great disappointment to us both that the record, for reasons which we never understood, wasn’t released.’”

When the music was ultimately released as the album Free for All [Specialty SP 2161; OJCCD- 1763-2, Leonard Feather commented in the original liner notes:“The existence of the present volume was unknown except to those who had taken part in it – and, particularly, the man who produced it, David Axelrod. ‘Frank and I were excited about this album,’ Axelrod recalls, ‘because it was going to be the first hard bop album recorded and released on the West Coast. We wanted to get away from that bland, stereotyped West Coast image. We worked for weeks on planning the personnel and the songs; the results were terrific. It was a great disappointment to us both that the record, for reasons which we never understood, wasn’t released.’”While taking some exception to the claim about the first hard bop album on the West Coast [and deservedly so as he notes the pioneering work in this regard by Clifford Brown, Curtis Counce and Harold Land], Ted Gioia in West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-60 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1992] goes on the state:

“With a strong supporting band of composed of Harold Land, Stan Levey, Leroy Vinnegar and Victor Feldman, Rosolino created some of his finest work of the decade. The arrangements are well crafted; familiar standards such as ‘Star Dust’ and … [‘Love for Sale’] take on a new luster through provocative tempo and rhythm changes.” [p. 221].

Love for Sale opens the album with the melody played behind Stan Levey’s 6/8 Latin figure that resolves into a wickedly fast, double-timed 4/4 bridge. The blowing takes place in a slower, medium tempo and Frank’s and Harold Land’s solos "… establish immediately that this is a tough, no-holds-barred blowing session” [Leonard Feather’s liner notes].

Love for Sale opens the album with the melody played behind Stan Levey’s 6/8 Latin figure that resolves into a wickedly fast, double-timed 4/4 bridge. The blowing takes place in a slower, medium tempo and Frank’s and Harold Land’s solos "… establish immediately that this is a tough, no-holds-barred blowing session” [Leonard Feather’s liner notes].A similar, finger-popping medium tempo is employed on Chrisdee an original by drummer Levey whose foot sounds like it’s going to snap through the high-hat pedal as he emphatically shows the soloists where 2 and 4 are and “don’t you dare try to speed this thing up.” It has been said of Levey that when he was playing time you can set your watch to it and this cut is a perfect example of that truism. The tune “… is a bebop line based on a cycle of fifths, with a somewhat Monkish bridge.” [Feather]

The ballad Twilight is an original Victor Feldman composition that also puts on display his skills as an arranger as there is no improvisation until Land begins a solo well into the tune. Frank plays the “beguilingly pensive” melody with Land sounding the chord root in the background over Feldman’s full chording and comping. It is a stunningly beautiful piece. Star Dust is the other ballad featured on the album.

The title track Free for All is a 24-bar blues original by Rosolino on which he employs his considerable arsenal of trombone techniques [including effortless sounding triple-tongued licks] to demonstrate that he really can play the blues. Land and Feldman join in for a few choruses to demonstrated that they too are card-carrying members and the chart comes to a close with a surprise ending!

There is No Greater Love is played in unison by the horns and taken at a crisp tempo that shows how wonderfully well Levey and Vinnegar work together and why the tune has been a jam session stand-by ever since it was written in 1956. The tunes chords “lay” so easily so as to make all of the solos sound effortless and uncontrived.

Sneakyoso is a Rosolino original that Leonard Feather describes as offering the quintet “an ingenious vehicle, its attractive changes providing good opportunities for Frank to work out. Note the fine comping Victor furnishes for Harold Land before taking over for his own solo. The two horns engage with Stan Levey before the head returns.”

As was the case with most of his recorded output, Frank was always interested in tempo and harmony changes to help the music sound fresh and new, and this is no less the case with everything that appears on Free for All.

Paired with J.J. Inc, I can think of no finer recording than Free for All to recommend to anyone wishing to hear the best of J.J. and Frank at work.

Many years later, after all of the East Coast versus West Coast nonsense had died down, I saw J.J. [who had, by then, been in Hollywood for a number of years writing for TV and the movies] sitting with Frank at Donte’s, a Jazz club and musicians hang-out in North Hollywood, CA. It was early in the evening before the set began and the two were having a quiet dinner together.

Many years later, after all of the East Coast versus West Coast nonsense had died down, I saw J.J. [who had, by then, been in Hollywood for a number of years writing for TV and the movies] sitting with Frank at Donte’s, a Jazz club and musicians hang-out in North Hollywood, CA. It was early in the evening before the set began and the two were having a quiet dinner together.I must admit to not thinking very much about it at the time, after all, given the number of TV, motion picture and recording studios located there, musicians having a meal or a drink together in Hollywood and its environs is a common enough occurrence.

Also, since that occasion, and especially after 1978, it was always difficult for me to think about Frank and his music, given the tragedy associated with his death. Matters weren’t help much in this regard with the news of J.J.’s suicide in 2001 after a protracted struggle with cancer.

However, some 30 years later, I came across the following quotation from J.J. and it helped me to recall the memory of that quiet dinner meeting and reminded me of how much I loved the playing of both of these trombone giants. That memory and this quotation prompted me to write this piece as a loving tribute to both of them:

“Frank Rosolino was a towering genius and a trombone virtuoso in the jazz genre. His style was unique and instantly recognizable. He was a warm, fun loving, charming human being and I miss his infectious giggle.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave your comments here. Thank you.